Source: recom.link

From 2 May to 1 June 2016, the ICTJ hosted an online debate entitled Does Collective Remembrance of a Troubled Past Impede Reconciliation?. In many societies, memorials to victims and rituals of remembrance have developed following periods of violence. These serve as reminders of the victims, and as a deterrent to repeating the mistakes of the past. In other cases, the truth has been buried, under the pretence that exploring the past would lead to a desire for revenge and further violence. Acts of remembrance can be manipulated to serve political purposes, and even to entrench societal divisions further; in such a situation it is relevant that the ICTJ ask whether forgetting the past is the only way to reconcile and move forward. The ICTJ invited UN Special Rapporteur Pablo de Greiff, a strong supporter of the role of remembrance in reconciliation, to debate over several weeks with David Rieff, the journalist and author, whose recent book, In Praise of Forgetting: Historical Memory and Its Ironies, suggests that remembrance can prevent reconciliation. Several guest speakers were also invited to draw on their own particular expertise in offering their perspectives on remembrance and reconciliation during the debate.

By Luke David Bacigalupo

The ICTJ Director of Programmes and Moderator, Marcie Mersky, opened the debate by asking whether, ‘If in societies emerging from violent conflict, where past events will be denied by some and asserted by others,efforts to open a broad platform to discuss the past, including by victims….will only impede reconciliation or lead to more conflict?’.

In his opening remarks, Rieff argued that remembering that there are some societies in which ‘memory does not mitigate but rather serves as a goad to horror’, and that in these circumstances, forgetting might be necessary to encourage reconciliation.

De Greiff, in reply, stressed that the methods and aims of acts of remembrance determine whether they aid or hinder reconciliation, not the act of remembrance itself. He warned that ‘Failing to acknowledge violations of the past, far from fostering reconciliation, is an invitation to instrumentalise the past’. He advocated the use of transitional justice to collect facts objectively, asserting that establishing the truth prevents the past from being used to oppose reconciliation.

The President of Tunisia’s Truth and Dignity Commission, Sihem Bensedrine, also provided some opening remarks. She posited that public remembrance is necessary because it is a part of holding those responsible for human rights abuses, including the state, accountable. Bensedrine contended that public remembrance rituals represent a guarantee from the state that similar violent actions will not be repeated in the future.

In his remarks of rebuttal, de Greiff added that it is better to have and be aware of a historical record that shows our capacity for violence than to have no record at all. He also posited that every person is a citizen of a community of rights, and that all citizens owe to each other the recognition and remembrance of their suffering. Rieff refuted de Greiff’s appeal to a ‘community of rights’, however, on the grounds that human rights and international law are subjective political ideologies; they are not an impartial way of dealing with memory, as De Greiff had suggested.

University of Arizona Professor Elizabeth Oglesby argued in her remarks of rebuttal that the idea that remembering is good is not widely accepted across the world, questioning Rieff’s assertion that remembrance is mostly seen as positive. Instead, she proposed that remembrance is often the result of a social struggle, and she stressed the importance of context in remembrance. As an example, she compared the USA’s ability to project its sense of victimhood around the world following 9/11 to the struggles for remembrance in Latin America, which normally aim simply to ‘dent’ an official narrative which does not acknowledge that acts of mass repression have taken place. She agreed with De Greiff that establishing the truth is important and truth commissions can provide significant support to victims; however, she disagreed with De Greiff on the impartiality of commissions. She argued that all memory projects, including truth commissions, instrumentalise the past to serve a certain aim, and so calls to forge should be scrutinized just as closely as calls to remember.

Gonzalo Sanchez Gomez, Director of the National Center for Historical Memory of Colombia, also made some remarks of rebuttal. He emphasized that local community projects which build relationships between people are more important to reconciliation than mass remembrance rituals. At the same time, in Colombia exercises in memory are helping to illuminate how the state was complicit in human rights abuses, and thereby contributing to perceptions as to how institutions should be rebuilt, which is a part of reconciliation. Sanchez Gomez contended that memory forces society to recognize a conflict as a part of itself. Societies that do not engage in remembrance are at a higher risk of falling back into revenge.

In her closing remarks, Moderator Marcie Mersky noted that Rieff had not explained ‘who exactly would make the decision for the society that forgetting would be a better option’. She said that the debate had demonstrated that ‘forgetting is no less neutral, or charged with power relations and political implications, than remembering’. Mersky concluded that the deepest divergence between De Greiff and Rieff was about the role and validity of the human rights framework. She proposed that this topic should be explored further in another debate.

In his closing remarks, Rieff criticized De Greiff’s ideas of a ‘community of rights’ as unsubstantiated, because international law, on which human rights rest, is currently suffering a crisis of legitimacy. Rieff finished by summarizing his main argument that, ‘there will be times when a nation or a community’s collective memory is so poisoned, partial, and self-exculpating, that the chances of a more humane narrative are so slim as to be virtually non-existent. It is in such cases that forgetting, or at least a radical de-emphasizing of the past, in favour of the present and the future, seems to me by far the better choice’.

De Greiff conceded that there is no perfect method for remembrance which can guarantee transparency, inclusivity, and a finality of interpretation of the past. Some methods, however, are better than others. Certain basic tasks can be accomplished, such as collating information about abuses, helping victims to participate, and establishing archives; and many other tasks too. A perfect account of the past is not needed; but we should try to reach the most reliable account possible.

New York Law School Professor and author Ruti Teitel’s closing remarks used the example of President Obama’s recent visit to Hiroshima to show that collective memory can be used to promote liberal politics and democracy. She argued that the purpose that collective memory is intended to serve is more important than the form it takes: remembrance can be used to promote violence or liberal democratic principles, depending on people’s intentions.

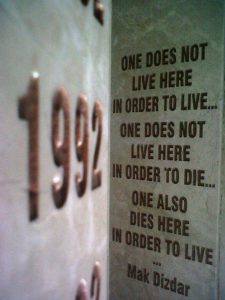

Note: Photos of the Kozarac Monument (Kozarac, Bosnia and Herzegovina)

The author is a graduate of Oxford University, and holds an MA in South-Eastern European Studies, jointly awarded by the University of Graz and the University of Belgrade. He is currently an intern on the RECOM project.