In March 1999, a bomb exploded in the Mitrovica marketplace. Rrahim Hasani’s five-year-old daughter Elizabeta dies on the spot. The other seven-year-old daughter, Elvira, got wounded on both of her legs.

Rrahim, now living in Podgorica, remembers the times when he lived and worked happily throughout Kosovo. He is happy that on the memorial plaque of the victims of that day, placed by the municipality of Mitrovica, the name of his daughter was finally added. Her name was initially not there. As Rrahim approaches the age of 70, widowed, half-paralyzed from the legs down, with no regular income, alone between four walls, he has one last wish.

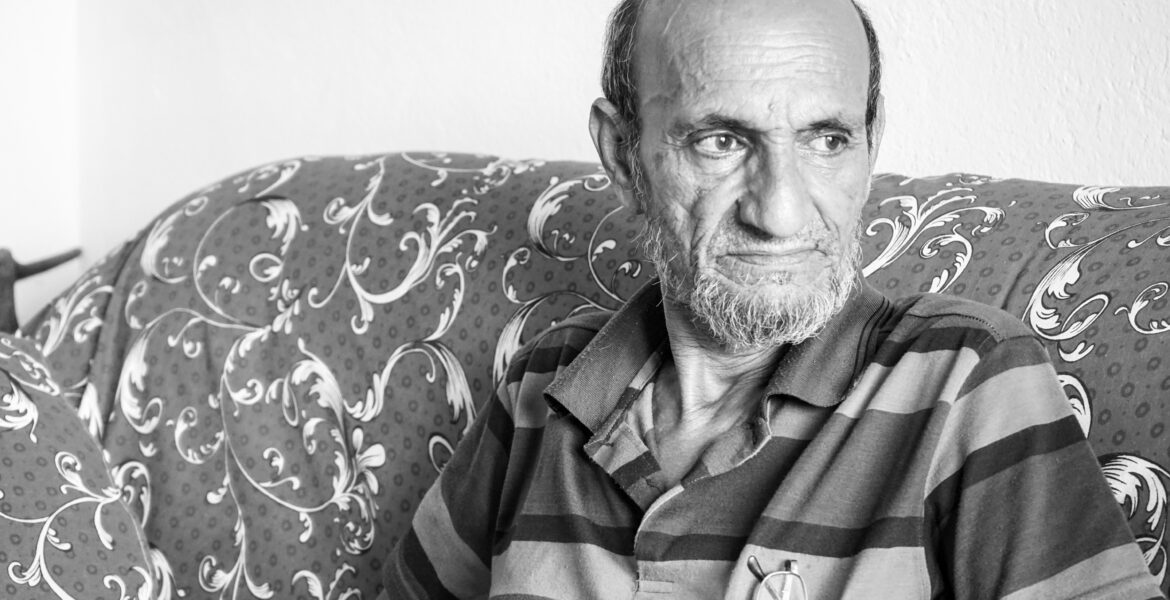

Rrahim Hasani

I am Rrahim Hasani and I was born on May 17th, 1953 in Mitrovica. My father Ramadan Hasani was from Mitrovica, and my mother’s name was Selvie Hasani. I had seven brothers and four sisters. We all got our education in Mitrovica. Each of us has completed high school. We were the first in Kosovo to make handmade brooms, which we would then go to the market and sell. We did well. My father went to Germany, and he worked there for many years. He earned his pension there.

I got married in 1972. In ’78 I had a civil marriage to my wife Nada in Mitrovica, and then we left Mitrovica, and we lived in Belgrade until 1996. I came back to live in Mitrovica because I reached a certain age and I had my house here. I came back together with my wife and children and I worked as a taxi driver from ’96 to ’98. My 75-76-year-old mother lived in our neighborhood. I never had any problems with anyone. Many people from Mitrovica know me because as a young boy I used to play music in cafes and hotels. They used to call me Rruti. The people of Mitrovica know who Rruti is, I would like to greet all of them.

My father was born in Bajgora, but he moved out very early from there, I believe he moved from there in ‘47 –‘48 and he went to Mitrovica. His brothers stayed back in Bajgora. He also had three other brothers – uncle Nezir, uncle Beqir and uncle Feriz. They all passed away, and one of them, Beqir, was my hairdresser in Mitrovica. He used to work in the Center, and my entire generation knew him because he was a good hairdresser.

My late father used to work in a factory. During Yugoslav times the factory where he worked did very well. They cooperated with Belgrade, Minhel was the name of the factory. In ’69 my father went to Germany, he stayed there for many years and he received a German pension. He was a driver in Germany and he even used to repair some machines there. When he received his pension, after the Germans overworked him, he didn’t live long. Just a year later he passed away. In ’80 he passed away at the age of 51, he was very young. My dad was a hard-working person. He knew nothing else but work. He never had any friends. He was a hardworking person and he minded his own business.

My mother didn’t go out much, she was a housewife. She worked around the house and she would read the Qur’an. At that time, she prayed all five daily prayers. She minded her affairs and she took care of the house. We grew up without a father because he was in Germany. My mother raised us, educated us, she taught us not to harm anyone. My mother helped us as much as she could with her own strength until she died.

All of my brothers were employed. One of my brothers, Isuf, worked in Zvecan, and he was a worker at the place where they melt gold. He retired at an early age because he got sick 18 times due to lead, the lead dust got into his blood. He received his pension, he was a good worker.

I had a brother called Tarzan, he was the owner of the company that made flowers. The other brother, Binak, wanted to join the police, but they refused him because he made some trouble in the neighborhood, and they kept him in prison for about 15 days and because of that he couldn’t join the police, even though he wanted to. He finished school for that line of work, he wanted to join the police but it wasn’t meant to happen. All of my brothers finished high school. They never did anything wrong to anyone.

I finished primary school in Mitrovica, the name of the school was ‘Svetozar Marković’. I also finished secondary school in Mitrovica. I had a friend from Peja – Ramiz Muriqi was his name. If he is alive, and if he reads this I would like to greet him, Greetings from Rruti, you know how much I love you. He finished school in Mitrovica, and he was a good friend of mine and I was very close to him. I apologize to his brothers Abdyl, Ahmeti, I hope they are still alive. I apologize to everyone, you are my brothers, you know that. I was at your house, I ate food together with you. I got along with them, I never had any problems.

Our family was very friendly and respected. We lived a good life. We made brooms and we would sell them. When a man works then he lives a normal life. We had enough to live a good life, we never complained and we never harmed anyone.

When I was at home, I socialized only with my brothers. When I went out to cafes to make music, I socialized with Albanians, because I played Albanian music. I socialized with Albanians, I had the Peja orchestra with the police, we played music when they had their banquets. If he is alive, I would also like to greet Shehim Krasniqi, he was an inspector, a very good man. I would like to greet Haxhia, Meti, all of them. I’m still alive, but I’m living in Montenegro now. You were all good to me.

I had a good relationship with Albanians, but that thing happened, my daughter was killed there. Everyone suffered because of the war. Everyone lost, the Albanians, the Serbs, us Roma, we all lost. But no matter what happened, life is good. Alhamdulillah, thank God Kosovo was liberated, it’s good. I am a Kosovar, man. If I went to the other side of the world, I say that I am from Mitrovica, Kosovo, because my father’s father was born in Mitrovica.

I have a brother who lives in Belgium, in Audergen. The others, live in France. They live in the city of Lyon. All of my brothers and sisters live there. One sister even bought a piece of land and she built her own house. They are living well, they have a good life and they don’t have problems. Sometimes we speak on the phone, sometimes they send me some money, sometimes they send whatever they can because Europe is not what it used to be.

At the time when I was at school, there was no hate. We, the citizens, were like family members to each other. Albanians know this, I ate and I drank with them. They slept in my house, and I slept in their house. I have some friends from my generation, I believe they are still alive, that know that I am telling the truth. There was no jealousy in Tito’s time. Now, I don’t know if Tito was good or not for everyone, I don’t know, but for me he was good. I had a good life, I had freedom, nobody offended me, I went where I wanted, at night, during the day, no one ever harassed me, nor did I harass them. But, now it completely changed, now these are different times.

I played solo guitar, sometimes also bass guitar, I even made a name for myself. In every well-known hotel, such as “Bozhuri”, “Theranda” in Prizren, “Pashtriku” in Gjakova, they all wanted to listen to my music. I learned to play the guitar myself. When I went to Greece in ’74 I entered a competition and I got first place, but in order not to lower Greece, that Greek composer for buzuki Theodore Rakitzis, said to me, “You can’t win the first place”. The commission said, “We need to put you in the second place because you are humiliating Greece with the way you play your instrument.” Because when they played the guitar, they played it using three fingers and I played it by using five fingers. It’s called staccato, playing it with five fingers. In ’74, I took first place in Greece, and I was a young boy. Journalists wrote articles, how I won among 36 cities. Then I was told, “You got the first place, but we have to put you second, we cannot put Greece in second, I will give you the second place because I am the best composer of Greece”.

I mean, I got into music and I loved it. For example, I played music with singer Dani. I believe that he lives abroad now, I don’t think that he is in Peja. I had a friend called Lan Burgiash. I would like to use this opportunity and greet Lan. I worked with Arif, Dërvish, and Xhaferi. They were musicians from Peja, and they were very good. I worked with them for many years in Peja. We played folk music. There is one song that I like, it’s called “I’m thinking of getting married.” It was very popular at the time.

Some songs touch you straight in your soul. Albanians would come, take out their money, and they would say, “Brother, take this and keep on singing, don’t stop”. At that time everyone could work, but there was not enough money. We had a circle of friends, we had love, friendship, we had a good friendship. There was no hatred at the time. I don’t know how everything turned upside down. At that time a different culture was present. Nobody cared who you are, what mattered was just if you are a good person. If you were a good person, all the doors would open up to you. I had a good time during my youth, especially with the Albanians, my people from Mitrovica know this. I worked with Mahmut Bakalli as well, I spent time with him in Deçan, we drank and ate food together.

I met my wife, Nada, in Belgrade. There has never been a more beautiful woman. She was together with her father in Belgrade checking out some books. When I first saw her I pulled her hair a bit. She looked at me, and I stared at her eyes, and wherever she went, I followed her. We started talking. After a short time, we ran away, because I had a son with another woman. Nada accepted him and she raised that boy. In 1998 my son was involved in a traffic accident in Italy and he passed away. Nada raised that boy. I took my wife in ’72, and in ’78 I married her, I left Mitrovica and I went to Belgrade in 1996. When I returned to Mitrovica, I became a taxi driver.

I had eight children with Nada. Now I have six daughters, with the one that died they were seven. I also have one son. Sadetja was first, then Selvia, Jasmina, Dragica, then Elvis and Elvira, Elizabeta and Maria Tereza.

Sadetja was born in Mitrovica in ’78. I had a big party at the Adriatic Hotel. Muharrem Serbezovski was popular then. I invited him because he was my friend. He came during the celebration for her first birthday. We had a great celebration. I took good care of my children.

I always wanted to fulfill all their wishes and I didn’t want them to have a childhood as I had. I wanted to give them everything they wanted, everything. I’m a parent who never yelled at my kids. I took care of them as much as I could. The eldest daughter got married at a young age and she went to live in Germany. The second daughter got sick at the age of eight. She had a fever and the temperature went up to 40, 41 degrees. For 15 days they couldn’t decrease the temperature in Mitrovica. And when she turned 38 years old, about five months ago, she passed away. She never bothered anyone, she was very calm. She played with her dolls, she was 38 years old and she still played with her dolls. She didn’t even know how to ask for food. We were giving her food.

Jasmina got married, and she lived in our neighborhood. I am very close to her. Dragica is named after my mother-in-law. My mother-in-law was Serbian. My wife’s father was a Muslim, Haxhi Drini from Gjakova, and her mother was a Serbian. She had five sons. None of the sons wanted to give their children the name of their grandmother, so I said to myself, “By the grace of Allah, I will name my daughter after her.” Dragica, my daughter, is married to a Montenegrin, a businessman from Niksic. She has three sons with him. They fell in love with each other. The Montenegrin came to me and said, “I love your daughter and I want to marry her.” I asked my daughter, “Did you inquire what kind of character he has? What kind of behavior does he have? What kind of person is he? Don’t come to me after some time saying that I gave you away. I wouldn’t want to hear you say, ‘You gave me away.’” And my daughter said, “Dad, I love him, he has good manners.”

Elvis and Elvira are twins. They always ate together. If they had chocolate, they would hide half of it for the other twin, sister for the brother, or brother for her sister. It was hard for them when they separated after the daughter got married.

And Elizabeta, at the age of five, had knowledge as someone who is twenty years old. “Where were you dad?” she would ask me. “Why, what happened?” I would ask her. “Do you know how much I cried for you, daddy” My wife would signal me that she didn’t cry at all but she just wanted to get on my lap. “I cried so much for you. Why are you leaving me alone? “and I would say, “Dear daughter, you are with your mom, sisters, and with your brother”. “No, when you are leaving me, I am crying all day long.”

Maria Tereza is the youngest one. She is now a mother of four children, she has two daughters and two sons. She is married and she lives in Budva. She is doing well, she has her own house and she doesn’t have problems. None of my children have problems. They are all right, I can’t complain about the in-laws.

I never visit my daughter’s in-laws, I don’t want to. Are my children happy? Yes. Then why should I go to the in-laws? I can have coffee at home. My daughters are coming to me, visiting me, they are helping me, cleaning, but I don’t go to visit them. They ask me, “Why don’t you come for a visit?” “My dear, I know that you are having a good relationship. If, God forbid, you wouldn’t have then I would come there.” As long as I am alive, I will never allow anyone to mistreat my children. I’m sitting here, taking care of myself. I’m lucky, I’m about to be 70 years old.

When I lived in Belgrade, it was an interesting thing about it, it’s a city open to everyone. You still have Albanians living there. Many TV presenters work in Belgrade because there are many TV stations there. No one bothers you if you mind your own business. Don’t put your nose where it doesn’t belong. Otherwise, you will find what you seek. For as long as I stayed there, I have never heard any offense from the people there. The work I did, I did it for myself. I tried to raise my children as best as I could. I had a good relationship with my neighbors. When the time came, I sold the apartment.

While I was there, I dealt with trading. We, Roma people, are good with trading, we buy here, sell there. But I decided to come back because I was 47 years old. I was thinking of my old age. I was thinking, “I have a job and my house in Mitrovica, what am I doing in Belgrade? I am going to Mitrovica, even if I die, I will die in my town, I will die where my house is”. My wife agreed with me. I sold our private apartment. I sold it to the mayor of Opština Stari grad. I sold it for good money. And so I came to Mitrovica.

To tell you the truth, I found Mitrovica in a little bit of a mess, there was a lot of Serbian police. At that time, there were no Albanians in the police. In ’96 there were no police, but there were some people, I don’t know what they were and from where they were. They behaved like madmen. By God, I was not used to seeing that kind of behavior. I even had a problem with an inspector. He asked me for my car because he wanted to take his wife and child to the doctor. When I said, “Give me back my car,” he said, “Oh, I am going to Montenegro because I am going to visit my in-laws.” I said, “No way, you will not take my car as long as I am alive, no way. You will get fired, you will see”. I went and I complained, I said, “I gave him my car so he could take his wife to the hospital” because Mitrovica was small, we all knew each other. That guy took his wife and children and went to Titograd. He was then fired because you can’t do things like that. What I am trying to say is that the police at that time were not normal.

In ’97 I was at the “Adriatik” when the police officers from Belgrade came. A two-meter-tall man pointed his finger towards me. I raised my hand and said ‘no’ with my finger. He came to me and asked, “Why are you not coming when I call you?” I said, “I am with my wife. You are pointing the finger at me as if I am your wife.” He said, “Show me your ID card!” I gave it to him. He looked at it and then he started saying some things. They did not behave well.

The Serbs, to be honest, had more power but they were not fair to the others. They were taking the food and drinks from women. The situation was pretty bad. They started the war. I would ask all the Serbs I had in high school, “Why did you put all these checkpoints? What are you preparing for?” and they would tell me, “You should look at your own business.”, “Man, but this is not okay. What are you doing?” I went to school with them, and so I was free to talk to them. Whoever had some kind of possession, they would take it away from them.

I was working as a taxi driver at that time, I was going everywhere. In ’98, the KLA caught me at the bus station at one o’clock after midnight. I was waiting for a man to come by bus from Podgorica. The bus would arrive at two o’clock after midnight. They came in a jeep, they were wearing masks, “Give us an ID card! Lay down on the ground.” I said to myself, “They are going to kill me.”

They left my ID card on my back, I don’t know where they went and what they did. They left me on the ground. After a while, I stood up, looked around but there was no one there. I took my ID card, took my car and I went for a drink, the passenger that I was waiting for arrived, I took him and we left. Why did they let me go? They saw that I am clean, that I am not involved in politics. Today no one is stupid. They have university degrees, people are smart. When you are righteous, no one will harass you. Whoever says otherwise is lying.

When we came from Belgrade to Mitrovica, one day I sent my daughter to buy bread at the bakery. When she came back, she said: “Dad, I am afraid to go buy bread because of the people here”. And those were our people, the Roma. I told her, “We are the same as them.” And she said, “No, no, they are dirty.” I could not convince her. She said, “Dad, I’m afraid to buy bread for us. I’m afraid to go near those people.” And so I went and I bought the bread. My children didn’t go to school. They didn’t speak Albanian. All of my children were born and grew up in Belgrade and they didn’t know how to speak the Albanian language.

In ’98 my eldest son died. As soon as he died, I left my wife and children, and after burying my son in Mitrovica I went to Italy. I was imprisoned in Italy for two and a half years, and in 2002 I came here to Podgorica. So, since 2002 I have been living here.

Nobody ever did anything bad to me in Kosovo, except for my daughter that was killed. My wife told me because I was in contact with her. She went out with children, my older aunt was there, she helped them. They went to the Serbian area, they went to Leposavic. Then they put her on the bus. They wanted to take her by bus to the Peja region. My wife asked them, “Where are you taking me with all these children?” Those Serbs asked her, “Show us your ID card. What are you doing in Serbia?” My wife knew how to get out of difficult situations. They saw that she had an ID card from Belgrade. “I am from Belgrade, my husband is from Mitrovica, I came here as a guest. Where are you taking me?” They let my wife go. She went out in Leposavic. She stayed there for a while, then some of my friends found her number for me.

I told her to come to Podgorica, but she didn’t know how to come because she didn’t travel much. I said, “Just take the bus to Podgorica. In a few days, I will get out of the prison.” When I came out from the prison, you know what I was seeing? Tents were all over the place, a complete disaster. They built some barracks in Podgorica. Those barracks were terrible, the rats would come to the trash cans. We stayed there until we moved into the apartment. When we moved to the apartment, I started crying out of joy. I said to myself, human life is bath, hygiene, and cleanliness. We moved here in 2005.

During the war in ’99, a few months before the bombing started, my wife went to the market. She took with her two of our daughters. One daughter was five years old, and the other seven. One was called Elizabeta, the other Elvira. A bomb exploded in the market. My five-year-old Elizabeta was killed there, and seven-year-old Elvira was wounded on both of her legs. Twenty-one years have passed. I would like to thank the brothers who came and got interested in my daughter, and I would like to thank the journalists who called me from Kosovo and got engaged to put her name and correct date of birth on the memorial plaque, and I believe they did. I would like to thank them and greet them. I have never been involved in politics, I have never owed anything to anyone. But anyway, it was wartime. Everyone lost something, both on your side and on our side.

I know who threw the bomb and I know the person, there is no need to say who he is. He was an Albanian, but he didn’t kill on purpose my child. He would have protected them, but it just happened. That bomb exploded and my daughter died. My other daughter had undergone several operations for several years.

I’m not saying that someone intentionally killed my daughter. She was hit and she died, but to be honest with you I am a little bit angry that 21 years have passed and no Kosovo association ever thought of coming to ask me what happened and how it happened.

Elizabeta was killed in ’99, I was in prison and they didn’t tell me. I was told by an Albanian from Albania, from Vlora, his nickname was Qorri. He said, “Rrahim, I will tell you something, just don’t tell anyone that I told you”, because there were some people from Mitrovica there. He said, “I think that one of your daughters died and another one was wounded in ’99.” I asked him, “Are you crazy?” and he said “Rrut, do you have a daughter called Elizabeta and an Elvira Hasani” And there and then I found out what happened.

When I left the prison, I met my family. They were staying at a place in Italy, but no one wanted to take them in, they were staying there at a place, I forgot the name where they were staying. I had Italian documents, a driving license, and an identity card. From here we took two vans and we took off and went there. And there I saw all my family members, my brothers, sisters-in-law, children, everybody was there.

I took them out of there, because my sister and nephew had a big apartment, because in Europe they provide you with a residence based on square meters, so we took them from there. Some wanted to go to Belgium, others to France. We went and left them all across Europe. I decided to stay here in Podgorica as long as I am alive. My mother died and she was buried in France. Also, one of my sisters died in France.

In the beginning, here in Podgorica, they were giving us aid every week. They provided us with food and drinks. They were bringing it with trucks. We never suffered for food or drinks, only the place where we stayed was not good. Some Italians were working there, and I started chatting with them. I had it better than the others. I socialized with the Italians, I spoke Italian well and I had a good time with them.

Elvira was wounded on both legs; she had many scars. She had undergone seven or eight surgeries, the kind that was removing skin from the side and filling the wound. She was skinny at the time but as time was passing, she gained weight more and more. If you would see her legs today, you would say, “This girl is lying, she was never wounded.” She was wounded on both sides; you could see her bone on both sides. Her flesh recovered and she got better. I always thought about whether she would find a man who would accept her with those scars. And yes, God willing, she healed well, she is now married and she is a mother of three children. She lives nearby here, in the neighborhood. She has a good life, she is doing well.

When my wife told me about Elizabeta, she said, “It was March, very cold, I couldn’t let them at home because the fireplace was burning, I couldn’t leave little children there. I took them with me, I wanted to do some shopping and to return home”. When they went into the marketplace, she bought what she needed, and she left the bag with two children. She told them, “Stay here because you might get lost in the crowd.” From that place, like a warehouse, only cheese is sold there, my wife went on the other side where vegetables are sold and then the bomb exploded. It was in a black bag. My wife told me, as people started running away, you could see people’s fingers in the wires. It was a big bomb. Elizabeta was on the ground, and the bomb ripped the flesh from Elvira’s legs. Those people that were running away, ran over Elizabeta when she fell. No one has told me this, but logic tells me. She died terribly, but what can I do? I guess that was her fate.

The army helicopter came and took both of them, they took them to the hospital in Prishtina. Elizabeta passed away. Elvira stayed there for about three days, the doctors operated on her legs and then they sent her back to Mitrovica. Also my wife was in the hospital at that time. She had an operation, they found some stones. Both mother and daughters were in the hospital. My late mother took care of my youngest children. She took care of them because no one else could do it since I was in prison.

Elizabeta was buried by my neighbors from the Factory street where we lived. By our people. She died in Mitrovica and she was buried in Mitrovica. Now they say that they put a memorial plaque at that place, a journalist informed me.

Some 12-13 years ago I took all my family members and I went from here to Kosovo. I wanted to see where my daughter was killed, but there was no memorial plaque. They put the plaque later. I asked for a document from the Albanians, no one gave it to me, also the Serbs didn’t give me anything. I went there for nothing.

I am a parent. When they put the memorial plaque without the name of my daughter, I felt bad. You can’t lie to yourself. A child is a child. I felt terrible because she was killed, and no association in Kosovo didn’t get interested to ask me, “Do you need help, Rrahim?” You are the first people to ask about my daughter in all these 21 years. I was disappointed because all the people from my generation knew me: Rroti, the guitarist from Mitrovica. I felt bad how no one asked me anything. If I had the power, I would take out the body and bring her here close to her mother and sister. If I could I wouldn’t leave her there.

Once they came, I think it was in 2004, to talk to me about coming back. It was a girl who knew me, she used to be my neighbor. “Rrahim,” she said, “your place is in Mitrovica.” I said, “I will not return. You know me, you know my life, I will not return.” She went, and others came. They were saying, you need to have the documents, I don’t know what they were saying. I said, “Brother, stop with all these lies. We can’t have two documents, both from Kosovo and Serbia.” They were saying, “Rrahim, we will find you an office job and we promise when your son grows up he will be a police officer”. I said, “No, I will not return.” They begged me to come back plus they promised me an 800 euros salary. This is what I was told, but I didn’t want to. I stayed here. I am working as a translator from the Italian language.

Like how everyone who has a mother knows, I don’t want to talk about the pain that Elizabeta’s mother suffered for her child. Everyone intelligent knows what pain the mother suffers. My wife died in 2015, in the seventh month. We buried her on the day of Eid. Suddenly she was out of breath. We drove her to the hospital. For two days she lived connected to devices at the hospital, on the third day we were informed that she passed away.

She was my friend. We never argued with her. I had a good relationship with her. Whenever she argued with me, I would go out for about 15-20 minutes. I would tell her, “Here is the wall, fight with the wall”. I would get out, when I would come back in, she would pour me coffee and apologize to me. I never hit her. I loved her, we had a good relationship. She was very beautiful. She had green eyes.

She suffered a lot for my son who died in ’98 in a traffic accident, she suffered a lot for him because she loved my eldest son very much. After he died, my wife’s health started declining, she started getting ill, she was upset, she smoked a lot, she was sad because she raised him herself. When my 31-year-old died, he left a wife and four children. Afterward his wife remarried somewhere in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. They took my grandchildren, and now my eldest granddaughter got married.

Then the thing with Elizabeta happened, and also my other daughter got ill, Selvie, and she couldn’t go anywhere without her. They were inseparable, wherever she went she would take her too.

As a father, I couldn’t wash anymore my 38-year-old daughter in the bathroom. A wise father doesn’t do it. I asked my youngest daughter, Tereza. I said, “Daddy can’t wash her anymore.” She said, “No problem.” Also Jasmina washed her. I would put her clothes in a bag, she would understand and she would go to her sister for a bath. Then my youngest daughter took care of her for five or six months.

But she had diabetes, and I didn’t know as a parent that she has diabetes. Sugar killed her. She didn’t know how to tell us, the sugar level went up to 40, the doctors then found out. Because of diabetes, she died. She died five months ago, not even five months.

It’s hard for me because I see the bed where she used to sleep and it’s empty now. I can’t sleep at night, I am alone with four walls. There is nothing I can do. You cannot fight against time. Sometimes the girls come, “Dad, take these ten euros, take these twenty euros”. They don’t have it for themselves. I am living one day at a time. I don’t spend too much. I don’t worry at all, things are good. You cannot escape your fate. Unfortunately, now I am having some health problems with my legs, and it’s a little harder for me to get out and earn some money because when I was healthy I earned myself.

I got some liquid in my legs and suddenly my legs started swelling. I was watering some flowers at the mosque. Early in the morning I would go and open the mosque, water the flowers and I would also wash my legs. I thought that cold water was refreshing my legs, but I was making my bones cold and I got rheumatism. I removed 28 liters of water from my body. When that liquid was removed, I got paralyzed. I couldn’t walk at all for four months, I only stayed inside these four walls. Just when that isolation period started, but thank God, I had a Muslim brother here. When I needed to, I just called him on the messenger, and he would come in a minute, he was there for me for everything I needed, for food, for drinks. God willing, now I am standing on my feet and I am walking a little.

I would like it if my daughter’s grave would be fixed. To fix it there in Mitrovica. Her name is Elizabeta Hasani. She is buried on the Serbian side, near the road that goes to Zvecan, on the left. Also my father is there, Ramadan Hasani. His tombstone is there. Ten meters above from there are my brothers Nezir Hasani and Ramadan Hasani. Just below my father’s grave is the grave of a son I had who died at a very young age. And then there is Elizabeta’s grave. I wish someone could fix her grave properly, maybe put a tombstone because I’m certain that she doesn’t have one. I would be thankful if anyone could do that for me.

The story is extracted from the book “Hijacked Childhoods: Accounts of children’s wartime experiences’ and is published in series as part of the framework of coordinated activities of CSO’s in Kosovo, organized to mark the International Day of Enforced Disappearances – 30 August 2023. The book is published in partnership between forumZFD Kosovo program and the Missing Persons Resource Center, and is supported by funds received from the German Federal Ministry on Economic Development and Cooperation (BMZ) and the Embassy of Switzerland in Kosovo. Prishtina, 2022.