Public space has long served to encourage social and cultural exchange and as a domain to both convey power or oppose it. After the Second World War, many public spaces in Kosovo’s urban areas – just as everywhere else in former Yugoslavia – were used as places to commemorate the fight against fascism, to celebrate victory, and to support the new nation-building. The erected monuments, with their unique and avantgarde styles – abstract and futuristic in shape, embedding deep symbolic and universal meanings– aimed at promoting respect, equality, commonality, and a shared identity among all the nations. However, following the 1990s wars and the fall of Yugoslavia, they lost their significance and have been since abandoned. Once great city landmarks, today erased from history and urban landscapes, remnants of a forgotten past.

The Partisan Martyrs’ Cemetery in Velania, Prishtinë/Priština, designed by Svetislav Ličina and built in 1961, is one of those forgotten monuments. It is a 240 m2 complex, consisting of several curved concrete arms (which when looked at from above symbolize an open flower), surrounding a red sphere shaped out of metallic beams. Underneath, the remains of the 220 partisans of Albanian, Serbian and Jewish ethnicities are buried. The monument is dedicated to the local partisan army revolts during 1941-1944, but the youngsters spending their days sitting atop the monument’s walls or by the stairs have no idea what it represents. Hence, they effortlessly express their presence on the site through graffiti or other derogatory writings on the walls.

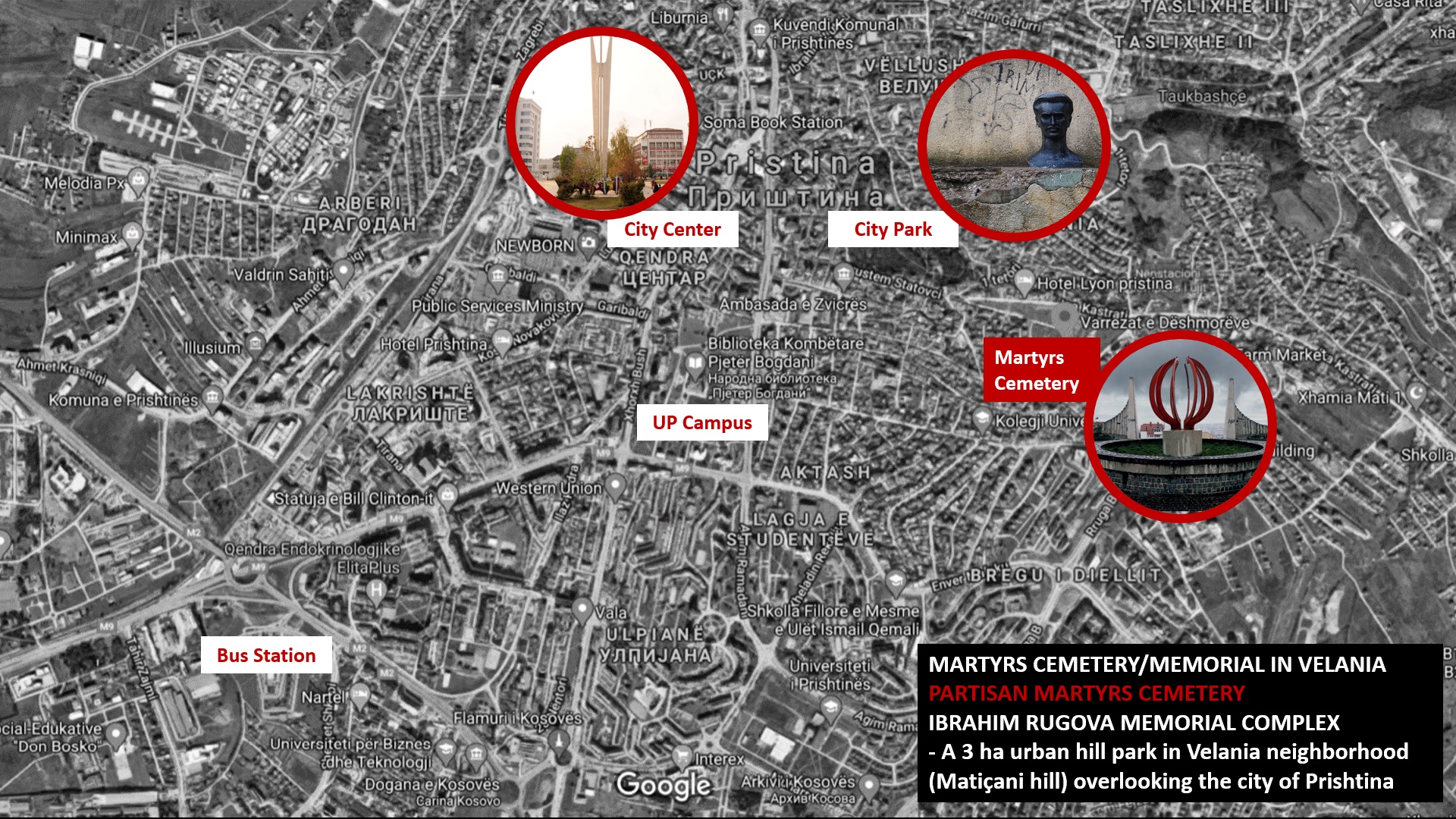

Such abandonment of this Second World War monument, its isolation and islandisation, becomes more evident when analysing its relationship with the broader context. In a radius of around 50 meters, the monument is surrounded by the grave of President Ibrahim Rugova (2006), the graves of around 26 Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) martyrs of the 1999 war, and those of other heroes and prominent figures of Prishtinë/Priština (relocated or buried throughout 2013-2019) – altogether sharing the 3 hectares Velania park.

The Partisan Martyrs’ Cemetery is not physically linked to any of the burial/commemoration sites; nor does it receive the same maintenance or attention level as the other ones, even though it is officially recognized as architectural heritage, albeit with a temporary protection status. It has undergone alterations from the original design (especially at the basement of the sphere) and lacks proper maintenance. It is also missing key elements, such as the information plaque at the entrance of the complex and the medallions with the martyrs’ names on the circular concrete walls.

In the physical context, all the different burial sites have different designs, styles, and construction materials. They are not linked to one another or to other features of the park (the amphitheatre and the small basin) properly. The park lacks open and proper access as it is almost entirely fenced. The inner pathways are not linked, hence reducing the area’s permeability. There are no activities happening there and no qualitative amenities are provided. There are not enough sitting areas or trash bins, nor any shade and greenery. In addition, there is no proper lighting within the park, besides the President’s grave area. In terms of representational aspects, there are different personalities – martyrs, national heroes, prominent figures, political activists – representing different ideologies. Some are commemorated through public events, whereas the others, such as the Partisan Martyrs’ Cemetery through smaller initiatives. Even during important commemoration days, the monument is overlooked by government representations as they move from one grave to the other.

The professional community, including architects and historians, have divided opinions on the Partisan Martyrs’ Cemetery, i.e., whether to keep it or not. As a result, there have also been plans to remove the monument and redesign the entire Velania Park into a memorial site representing the 1990s and onwards. However, following the increased opposition of the Second World War Veterans and other civil society organizations that support a more holistic historical and artistic representation, the monument has managed to survive to this day. Selective and uncoordinated developments in the park have proven to be unsuccessful; Velania Park remains fragmented in both the physical context and representational aspects.

However, artists and sociologists, as well as tourists, have a profound interest in the monument. Evidently, there is embedded potential within the monument to present history, attract tourists, and talk about art but also social transformations. Residents too want no additional graves in the park, and they have protested about the expansion of burial sites several times. They simply want a well-planned and safe public and green space, a need that became even more apparent during the COVID-19 lockdown measures!

So, how can we transform the park into a successful, safe and well-planned public space, which besides serving as a place for remembering the diverse past and reflecting on the future, can also contribute to fulfilling current citizen needs, improve their health and wellbeing, and build community ties? When dealing with such charged spaces, one should start from the very beginning – creating a public space by the people for the people – a park that is well-designed, easily accessible for all (without fences), permeable and well-connected, which provides proper urban amenities and recreational opportunities. With the growing urban densification in Prishtinë/Priština, as well as in the adjacent neighbourhoods, there will definitely be an increased need for utilizing this green space. Besides, a proper design and narrative of the overall park could also turn it into an educational space or a more frequented touristic destination, which with all its diverse representations could provide a more holistic story of Kosovo’s history.

Velania Park has the potential to turn into a comprehensive memorial site, but its transformative process needs to be addressed jointly by several stakeholders, including local and central government institutions (the Municipality of Prishtinë/Priština, the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports, the Agency for Memorial Complexes Management), academia, experts (architects, urban planners, artists, historians, sociologists, economists), CSOs (cultural heritage, tourism, economic development, dealing with the past), businesses, neighbourhood residents, and other citizens or interested parties. But how do we design current places of remembrance consisting of mixed representations (time periods, contexts, narratives)? What histories or collective memories are represented? How do institutions engage in keeping these memorial sites and memories alive for future generations (maintenance, management, events)? All these questions can only be further elaborated through participatory visioning and multi-stakeholder cooperation for the park’s concept and future development. It is crucial to remember that we cannot just erase parts of our history, but rather wear them proudly while striving to create a better future.

.jpg)