Source: http://www.balkaninsight.com

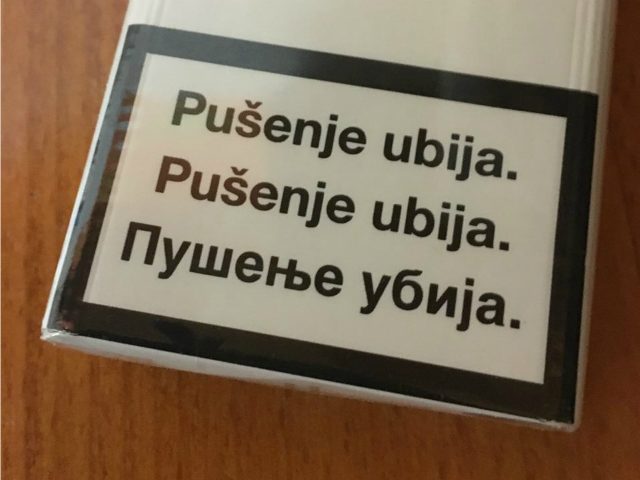

Anti-smoking warning “Smoking kills” on a packet of cigarettes in Bosnia, written completely the same in all languages, with the only difference is that the Serbian warning is written in the Cyrillic script. Photo: Facebook/Sava Mandic

A declaration that Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin and Serbian are all variations of the same language has annoyed conservatives, but received a warmer welcome from the people who speak it.

A group of NGOs and linguists from Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro and Serbia are to present their Declaration on the Common Language in Sarajevo on Thursday, in an attempt to counter nationalist divisions in the former Yugoslavia.

They argue that people in the four ex-Yugoslav republics actually speak a polycentric language – a language which has several different standardised versions in different countries.

“We, the signatories of this declaration, believe that the existence of a common polycentric language does not call into question the individual right to express one’s belonging to different nations, regions or countries,” the declaration says.

Although there are four separate official languages – Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin and Serbian – speakers of each language understand each other perfectly, despite linguistic variations.

Some linguists claim that even bigger differences exist between the different variants of German – in Germany, Austria and Switzerland – and that the four ex-Yugoslav countries’ tongues are dialects and not separate languages at all.

“Nationalism is increasing by introducing a purist approach towards language in schools and in media, because people, in relation to the choice of words, are trained to associate the term ‘good’ with their own nation, and the term ‘bad’ with other nations,” explained Croatian linguist Snjezana Kordic, who worked on drafting the declaration.

The declaration was drafted by 30 linguists from all four countries, through a series of regional conferences in Belgrade, Sarajevo, Podgorica and the Croatian coastal city of Split.

It has been signed by over 200 linguists, writers, scientists, activists and other public figures from all over the region.

It grew out of a project initiated by Belgrade-based Association Krokodil, which organises cultural and literary events, and the Balkans branch of the German ForumZFD, which funds peace projects in the region.

“The declaration has an educational role because it explains that a polycentric language is a normal thing in the world because English, German, Spanish and many others are that type of language,” said Kordic, who has been criticised by conservative linguists in Croatia.

She suggested that referring to a common language could potentially lead to the end of the phenomenon of schools being divided according to which language the pupils speak, as happens in some places in Croatia and Bosnia – and “stop producing future generations of nationalist party voters”.

In the former Yugoslavia, from 1954 onwards, Serbo-Croatian (also sometimes referred to as Croat-Serbian) was the official language in all the republics of the former state.

However, in 1967 Croatian intellectuals and linguists signed the Declaration on the Status and Name of the Croatian Literary Language, which was seen at the time as a nationalist provocation.

Language remained a tool for the preservation of national identity in the 1990s, and when news of the Declaration on the Common Language became public, some more conservative linguists rejected the idea.

Zeljko Jozic, the head of the Croatian Institute of Croatian Language and Linguistics, told Vecernji List newspaper on Tuesday that such initiatives are “unnecessary”.

“The Declaration on the Common Language, which I admittedly haven’t seen, but by the very name and what can be read about it, I can say that is also going to one of those pointless actions that can’t have a serious impact on [the] Croatian, Serbian, Bosnian and Montenegrin [languages]. In particular it can’t affect the 24th official language of the European Union – Croatian,” he said.

He recalled the 1967 declaration and how Croatian intellectuals fought for the Croatian language “when such an opinion was quite unpopular and could have severe consequences”.

“Since 1990, in the Croatian constitution, it has been written that the Croatian language is the official language of the Republic of Croatia and this is a fact that, regardless of such declarations, statements or one’s desires, will not change, nor can such an action in any way endanger [that],” Jozic added.

Another distinguished linguist, academic August Kovacec called the declaration “a provocation and a non-sense”, Croatian news agency HINA reported on Tuesday.

Some Croatian politicians have also expressed dissatisfaction with the idea.

“How could I sign that? Who could support that in Croatia?” Croatian Prime Minister Andrej Plenkovic replied to reporters in Zagreb on Wednesday when asked if he had signed the declaration.

“The issue of the common language is a political construct that came with one state in 1945 [socialist Yugoslavia], which was never implemented in reality however,” Croatian Culture Minister Nina Obuljen Korzinek said on Tuesday.

“It was called the Croat-Serbian language, but in school we all learned Croatian and wrote in Croatian. I don’t understand what would be the goal of starting such an initiative today,” she added.

No obstacles to understanding

While Croatian linguists and politicians are protective of their language, some of their fellow citizens appeared to be more flexible.

“I refer to my language sometimes as Serbo-Croatian, sometimes as BHSCG [an acronym for Bosanski-Hrvatski-Srpski-Crnogrski which is often used by international organisations operating in the Balkans], and in informal conversations, I say ‘our language’,” 30-year-old office clerk Josip from Zagreb told BIRN.

“When the conversation turns in that direction, I usually mention that most of the languages of the former Yugoslav republics are simply politically divided, but that these [languages] are simply different dialects of the same language,” he replied when asked if he understands the other languages.

Fifty-nine-year-old Sanja, who works in a bank in Zagreb, said that she refers to her language as “Croatian” and says that she also understands all the other three.

“This is normal because I lived for a long time in Yugoslavia where films, the press, TV programmes and books were very often from all over Yugoslavia,” she told BIRN.

But she said she thinks that declaring that all four represented a shared language was “unnecessary”.

People in Bosnia and Herzegovina – a country where the Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian languages are in equal use at all levels and in all state institutions – also told BIRN that they thought it was the same language, although they were less sure about what its name should be.

“I think that whether this all is one language is not even a question. It is, and everyone will probably agree. The question is, actually, what would we call it?” Midheta, a 54-year-old school teacher from Sarajevo, told BIRN.

“I don’t believe this is a linguistics issue, but a political one,” she added.

Nermin, a 30-year-old software developer from Sarajevo said that translating from one language to another “makes no sense”.

“Having Croatian subtitles on Serbian-language TV shows makes no sense. Don’t even get me started on those cigarette packets,” he told BIRN.

All cigarette packets for the Bosnian market must have the anti-smoking warning written in all three languages, which leads to situations that the message “Smoking kills” is written completely the same in all languages, with the only difference is that the Serbian warning is written in the Cyrillic script.

One language, one name?

In Montenegro, the declaration has been signed by several scholars, writers and public figures, including writers Balsa Brkovic and Brano Mandic and activist Maja Raicevic, but it has not been a prominent issue in the Montenegrin media.

Montenegrins however seemed to support the initiative, with some saying it was about time that someone came up with such an idea to set aside the nationalistic disputes over the language that everyone uses.

Gorica Jovovic, a 54-year-old teacher from Podgorica, told BIRN that if the declaration was offered to ordinary people in the four countries it would attract a million signatures of support.

“The Montenegrin, Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian language are the same, whatever people think,” Jovovic said.

“It has always been the same language. But the new political winds started blowing in the nineties so they changed the name,” said Milisav Popovic, a pensioner from Podgorica.

In Serbia, there also seemed to be a positive reaction to the idea of a shared language.

Kristina, a 25-year-old manager from the northern town of Zrenjanin, pointed out that there were no barriers to communication.

“The whole idea of separating the languages doesn’t make any sense to me. We understand each other perfectly well, and we can have very deep and complicated conversations and discussions without additional linguistic explanations,” she told BIRN.

Kristina said she believed that there should be a common language – saying she was “OK with the name Serbo-Croatian” – seeing it as a way of preventing people from moving even further apart.

Dusko, a 44-year-old manager from the city of Novi Sad, said he also welcomed the idea of a common language.

“I support the initiative for giving all ex-Yugoslav languages one name. But I also supporting the protection and the nursing of all the differences and specifics of all these languages,” he told BIRN.

However, Nermin from Sarajevo pointed out a major political obstacle to the idea.

“What would we call a joint language without offending anybody?” he asked.

“Maybe Euroslavic?”