Just as during all other years, the recent news about the 26th anniversary of the beginning of siege of Bihać region went unnoticed. It was mentioned only briefly in the local media. The first associations that I have in case of such anniversaries and memories of the siege are shrapnels that missed me by a few centimetres, exploding shells, deaths of friends, cousins, acquaintances. A piece of news about someone’s death was like weather forecast. Brief, cold, banal. And news about the death of known and close people were seen as something normal and natural. In the maybe most sensitive age, we faced human destruction and sadism in the most brutal way.

Nevertheless, even in such times, children’s wish to live was stronger than anything else, so that even the worst things turned into a game. Immediately after a shell would explode, we would run to the place of explosion to collect the hot shrapnel, which we would later on exchange as cards. For a bigger shrapnel, one would get several smaller ones. As the war progressed, the games became more serious. The daily shelling and news about death resulted in hatred and anger. Unconscious of the potential consequences, we excitedly threw hand grenades into the river, sometimes we would go to the front line without anyone’s knowledge. We were 14, 15 and 16 years old and we were ready for anything. At such moments and such an age, fear almost does not exist. It comes later, in a much more insidious form.

I do not intend to describe my own memories from the war, because many other persons had much more brutal and worse experiences. This is only a small fragment of what was happening during the siege, which is only a superficial and deliberately blurred information for the media and the public in Bosnia and Herzegovina. If Bosnia and Herzegovina were a normal state, all media would devote at least one sentence to the anniversary of siege of Bihać region on June 12.

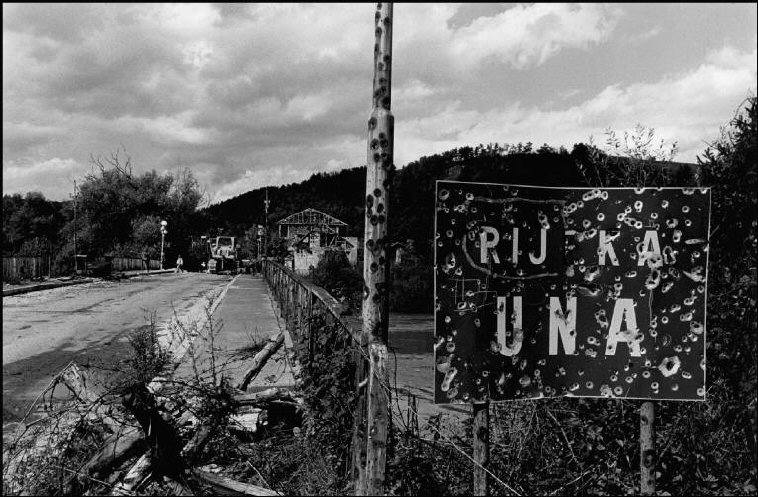

If there were a minimum wish to know the truth, it would be widely known that around 200,000 civilians in Bihać region (Bihać, Cazin, Bosanska Krupa, Velika Kladuša, Bužim) were under siege for the unbelievable number of 1201 days, from June 12, 1992 to August 6, 1995. The city was under siege and attacked by the Army of the Serbian Autonomous Area of Krajina (SAO), Army of Republika Srpska and National Defence of Western Bosnia (units that were under the command of the Red Berets from Serbia). Dozens of thousands of shells fell in Bihać region during the siege. According to official data, 5,000 persons were killed or disappeared. Another specific characteristic of Bihać is also the fact that there was a chemical and biological attack against the civilian population and there is evidence of this. Poisoned food was delivered to Bihać in the form of humanitarian assistance. Due to a lack of responsibility of institutions, the consequences of the poisoning still remain unknown. Except for alleged excessive number of cancer cases in Cazin area, there are no other analyses.

Nobody considers the siege of Bihać area important, including also the institutions and the public in Bihać itself, at least not in a way that would be worthy of such an anniversary. The fact that the media have been ignoring it for years has yielded results. If today we were to poll persons in the countries of the region, and even in Bosnia and Herzegovina, about the siege of Bihać area, most respondents would probably not be able to pronounce even one sentence that makes sense.

The brutality and almost daily shelling of civilians in Bihać area, which had been ongoing for three years, have been overshadowed by public discussions about ”more current topics”: the operation Storm of the Croatian Army, which ended the siege of Bihać, and military success of the 5th Corpus of the Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina later on. The first associations of Bihać and the war imposed by the media and online discussions are the conquest/fall of Krajina municipalities, the Fifth Corps, General Atif Dudaković, operation Storm, smuggling, expulsion of Serbs from the Serbian Autonomous Area of Krajina. Only two articles about this topic can be found online. The text of Mirza Sadiković, a journalist from Bihać, and Dragan Bursać, a columnist of Buka and Al Jazeera.[1] Writing and dealing with the siege of Bihać area is simply not interesting enough and worth of attention of regional and Sarajevo-centric media.

On the other hand, some media, such as RTRS, have never even tried to move away from propaganda reporting, which had been defined a long time ago, and to approach the topic in a humane and fact-based manner. In addition to the media, public institutions are also ignoring it. The Cazin Krajina region has been neglected and forgotten in the post-war period in economic, political, cultural terms, but also in relation to the process of facing the past. Numerous NGO projects focused on facing the past have rarely been dealing with this region. Numerous conventions, memory modules, conferences and round table discussions devoted to war memories, facing the past and transitional justice are not held in this part of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The reasons can often also be banal, such as a great distance from Sarajevo.

There are also more serious reasons. It is difficult to accept the fact that branding and marketing can also be applied on the sphere of culture of remembrance and introduce value differences in memories. The editor of Slobodna Bosna, Senad Avdić, mentioned long time ago that foreign media made war-related tourist destinations out of Sarajevo and Srebrenica, whereas other places in Bosnia and Herzegovina have become fully forgotten by the media. Just as the foreign media created war-related tourist destinations, public and private media in Bosnia and Herzegovina have created exclusive anniversaries and memories in the post-war period. Giving exclusiveness to certain events, which are usually also used for political purposes, has prevented a healthy relationship towards the past throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina and opened up the possibility for twisting facts and the truth.

As regards the local level, the situation is no better. Political elites have failed (or they had no intention to succeed) in paying their respect to their fellow citizens and approach the topic responsibly in order to create a culture of remembrance, establish and disseminate the truth about the siege beyond the local level. There is no museum of siege, memorial centre, monument or specific and open dialogue about the siege of the Bihać area.

The failure to mention and open up good public discussions about this topic at higher levels, but also in the local community, contributes to oblivion and wrong memories about that period. Events organised to mark the suffering in Bihać area are frequently used for political manipulation and strengthening the political power and impact. There is probably no such event in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which has not been characterised by political speeches, and in case of Una-Sana Canton, they certainly relate to eulogies about SDA, the party that ”saved Bosniaks and Bosnia”. Remembering the war in a society divided along ethnic lines is dictated from the nationalist ideology power centres. In her publication ”Politicised Memories: Fight for the Territory of Collective Remembrance”, Snježana Kordić stresses that ”the ideological propaganda cares very much to use schools and the media to instil in the population such a story about the past that would justify, and even make seem inevitable, what is in the interest of the nationalist elites in power. Their goal is to cement the dominant ideology through what they have been presenting as history”.[2]

An open dialogue without political pressures, which would question the importance and role of individual and collective remembrance of the siege and spread the truth about the siege, failed to emerge. Opportunities to provide reparations to victims, such as giving them back at least some of their dignity destroyed by the war, providing them with various forms of psychological and physical protection and assistance and symbolic activities such as public excuses, are probably gone forever. There is no dialogue in other spheres either. The interest of citizens has never been the goal of political structures. The communication they know is totalitarian, top-down.

Dialogue is important for a number of reasons. As Goran Božićević says in the analysis ”Work on Facing the Past”, the maybe most important form of facing the past is the one that reveals the causes and initiators of war: ”Revealing war investments, secret relations between the elites of alleged enemies.

The one that restricts the space of lies and manipulations through facts. The one that eliminates taboos, brings them into an open space and encourages discussion about them”.[3]

Given the fact that there are no institutional efforts to approach this topic seriously, an important virtual platform about the siege emerged. The Facebook group Bihać ratne fotografije (war photographs) has more than 13,000 members. The page is mostly devoted to remembrance of the killed members of the Fifth Corpus and it soon became a platform for sympathy and discussion between persons, who share the same pain, who lost their dearest ones or suffered some other trauma. That is the place where they find those things that both local and state institutions have not even attempted to ensure – emotional support and empathy.

However, even here remembrance is used to support one or another political option, consciously or unconsciously. Can collective remembrance even be established at human level, devoid of political, ethnic and religious connotations? That very same political party, whose supporters believe that it has the exclusive right to remembrance, over more than 20 years of governance in this canton, has left behind a territory from which persons emigrate in masses.

Selfishness, greed and incompetence of political actors, but also citizens that benefit from such governance, that got jobs or eternal CEO positions, has achieved in this region what the siege has not – it has expulsed numerous young people, some of them forever. Kombiteks, Krajina metal, Žitoprerada, Polietilenka, companies that had employed thousands of persons, were destroyed in the post-war privatisation under SDA government. The injustice done in the recent past at all mentioned levels has a serious impact on our individual and group identity. It has such an impact that leaving this society becomes the only hope in the end.

Adis Šušnjar is a journalist and executive editor of the portal inforadar.ba. He is the president of the Media Activism Association (UMA). He holds an MA degree in journalism. He worked as a journalist at various media, edited the newsletter E-novinar and worked as a project coordinator at the Association of Journalists of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

[1] http://balkans.aljazeera.net/vijesti/sutio-sam-dok-je-bihac-granatiran

http://balkans.aljazeera.net/blog/dan-kada-je-sloboda-stigla-u-bihac

[2] Interdisciplinarne učionice, 2016 – Politizirana sjećanja: borba za teritorij kolektivnog pamćenja, Sarajevo 2017.

[3] Rad na suočavanju sa prošlošću, Dokumenta, Centar za suočavanje sa prošlošću, Zagreb, 2012/2013.