Whether at a crime scene, on a chair, or at the computer, forensic examiners, who have examined the persons murdered in Kosovo and in other countries, were exposed to the experience of atrocities and have testified about those. They have identified the missing, helping connect their remains with the families. They have used examinations as a tool for criminal justice, while also bearing the burden of their work. Four of them who have worked in Kosovo tell their stories: Valon Hyseni, Robert McNeil, Luísa Marinho and Javier Santana. A blog series by Serbeze Haxhiaj.

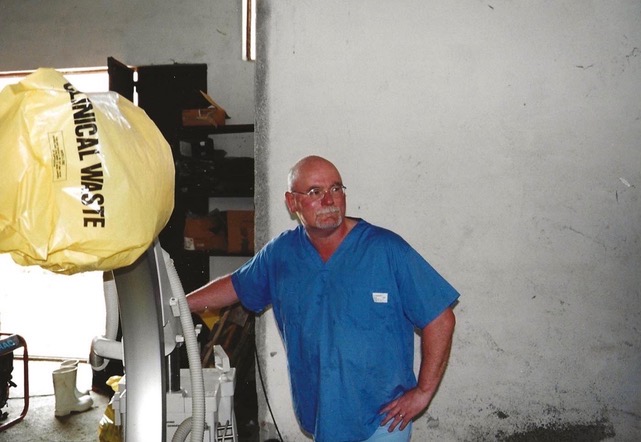

Robert McNeil: The shadow of grey faces

The story of Robert McNeil is not just a story of a forensic examiner who examines the bodies of the bodies. In the heart of his story is his experience in collecting evidence of genocide and crimes against humanity committed in Bosnia and Kosovo in the last decade of the previous century.

After more than 20 years of examinations in his country, Great Britain, McNeil was invited to join international forensic teams to examine the persons murdered and buried in mass graves in the war areas in the Balkans and Africa.

When he started to work for the team in charge of examining the bodies of the murdered in the Srebrenica massacre in Bosnia, for McNeil and his colleagues that was a “shock” as they had to determine the causes of death for so many people at the same time.

“Until then, none of us had worked with so many murdered and mutilated bodies. Many of those had their hands tied and eyes covered. They had experienced so much suffering until their death,” he says.

For the forensic experts, it was horrendous how they had tried to cover up the crimes. “The examinations we conducted simply testified genocide,” he says.

His account brimmed with anxiety as he journeyed right into the dark heart of the atrocities committed during the dissolution of the Yugoslav Federation in the 1990s.

The history of McNeil is part of the untold stories of forensic scientists who worked to join together families with the remains of their loved ones that were dispersed all over the place, and to bring perpetrators before justice.

“Through the autopsies we understood what people are capable of doing when they are blinded by hatred and prejudice,” he says.

McNeil says that no matter how much you try not to get involved, atrocities like the one in Srebrenica leave a deep mark on the human being.

Experiencing such atrocities became scarier for him when he came to Kosovo in June 1999 as part of the teams of the International Criminal Tribunal for former Yugoslavia. “There were many children. Some of the bodies were still fresh. It was extremely hard to face the anxiety they induced,” he says.

“As we were exhuming them, our breath would stop inside our plastic overalls,” McNeil recalls.

Through clothes and bullet marks he has scanned thousands of pains felt by the victims until they died.

He says that during the examinations in Srebrenica the team was analysing the marks on a jumper that had a bullet hole with a falling trajectory in the lower part of the spine. “It seemed they were kneeling when they were killed, or forced to kneel. Later, it left a mark on us,” says McNeil.

He says that searching for the missing is often an endless process but not a hopeless one. “Through DNA, we have identified hundreds of British and Australian soldiers killed and buried in mass graves in France during World War One.”

His experience as a forensic examiner during the most expansive international investigation in the history conducted by the International Criminal Tribunal for former Yugoslavia became a mark of evidence of crimes against humanity committed in Bosnia and Kosovo.

The history of his work, at a large part, involves facing the “grim faces”, as he has described them in his book of memoirs.

McNeil poses universal questions, in an attempt to understand the scale of atrocities committed against so many civilians in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo.

“Many of the atrocities that were committed, especially in Srebrenica, intended to humiliate the victims, especially when we talk about the rape of women,” he says.

During the years of examination in Bosnia and Kosovo, McNeil kept a journal, because, as part of the team, he was not allowed to take photographs or keep personal notes.

It seems that both he and the others had closed off their minds to the horrors they witnessed, focusing on the scientific verification in order to do what they had to do.

For him, the psychological cost came later, after he retired and the ghosts of the places he had worked at started to trouble his sleep.

“Later, I started to experience symptoms of anxiety, relive the horrible scenes, and have nightmares,” McNeil says.

It was his turn to treat the post-traumatic stress, which he did through art, when he started to paint .

“I have treated it through art. From time to time, I still have nightmares. But I am used to accepting that this is how it is,” says Robert McNeil.