Regardless of how conflicts are solved, people in these areas will continue to live together. We all need peace; therefore, we must work on developing the democracy and achieving economic, social, and ecological well-being. Our interests are the same; war and violence harm everyone.

From the Charter of the Anti-war Campaign

This year marks the thirtieth anniversary of the launch of the Anti-war Campaign Croatia (colloquially known as AWC), which is a network of peaceful, human rights organizations and initiatives that have greatly influenced the development of the current civil society in Croatia. This year also marks the tenth anniversary of the publication of the first monograph of AWC, which united many former AWC members in an attempt to systematically document its work and reflect on its importance from a distance enabled by the early 2010s.[1]

The previous decade was marked by a wide use of the term ‘institutional memory’, which indicates not just the need to reconstruct and rethink the specific way organizations work, but also one’s own position and mission in a broader societal context. Nowadays, the situation in the life of civil society organizations is primarily characterized by bureaucratization, exhausting administrative pressure from various donors and domestic legislation, uncertain working conditions, an overabundance of tasks and lack of resources necessary to complete them, a tendency towards professionalization instead of activism, a clear thematic direction of these organizations, and unpopular status in the society. It is worth noting that such a combination of scarcity and discipline fails to contribute to the development of institutional memory. Survival goes against the development of organizations as alternative institutions.

Some of these characteristics were shared by civil society organizations – under the more common term of NGOs – even thirty years ago. However, we could argue that back then, the situation was in many ways more chaotic and overt. A country was falling apart, a new one was being formed; the dominant social values passed through a deep process of revaluation; the country was facing war and total militarization of the society. In that respect, the role of the AWC was twofold: it not only provided a frame for uniting individuals and initiatives around specific social problems, thus building the potential for autonomous civil association, but in a broader sense it also represented the strengthening of the society versus the state – or rather the decrease of state intervention in the society – what we understand to be one of the pillars of the rule of law. This also relates to the formation of a specifically anti-war position, i.e., the articulation of the defence of civility in a war-torn country.

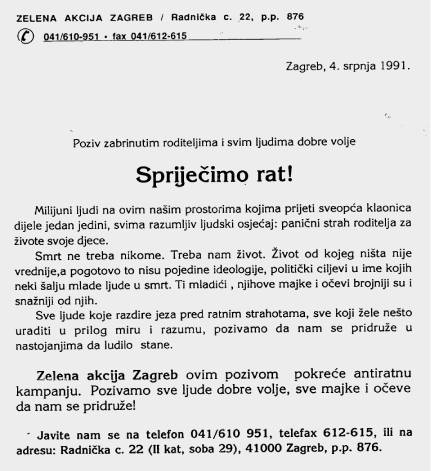

Even though it was built on an already prolific heritage of antimilitary, pacifist, alternative associations from the 1980s, the establishing and the work of the AWC was a continuous evaluation of one’s own position in real time. The anticipation of such an arrangement, while the Yugoslav crisis was in full swing, can be tracked through the correspondence of the Green Action archive, one of the first independent associations of citizens in Croatia, established in the early 1990s. During the Spring of 1991, a series of public actions was already taking place, and on the fourth of July, Green Action sent out the appeal “Let’s Stop the War!” At an informal meeting that day, held at the garden of the Zagorka restaurant at the corner of Držićeva Street and what used to be the Proletarian Brigade Street (nowadays it is called Vukovar Avenue) the launch of an anti-war campaign was being planned, and the Charter was written the very next day. The Society for the Improvement of Quality of Life joined the campaign on the same day, and along with the Green Action, worked intensively over the next two months to garner support.

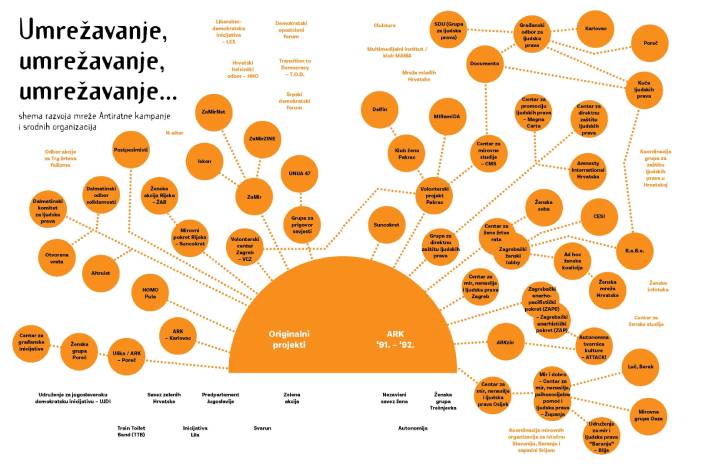

As the political situation grew more complicated, the initiatives within the AWC flourished. The list of their projects is vast, and other independent organizations grew from them, some of which are active to this day. For example, the Center for Peace Studies evolved from the Volunteer project; Amnesty International Croatia evolved from the Group for Direct Protection of Human Rights, and Union 47 stemmed from the Group for Conscientious Objection, seeking active legal regulation of the right to conscientious objection. The association ceased to exist after the successful fulfilment of its goal. Two books were published in 1993 about war crimes in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. ARKzin began as a fanzine of the AWC, and over time became one of the rare independent opposition newspapers in Croatia in the 90s. Currently, it serves as an extremely useful source for the study of the civil society scene, whose development it has closely followed.

The first autonomous cultural space in Zagreb – Attack! – emerged under the auspices of ARKzin and Zagreb anarchist groups. The AWC promoted topics that had been neglected or were non-existent in the public sphere: women’s rights, the gay and lesbian community, environment protection, independent culture, and volunteering. The development of the AWC as a horizontal network is at the same time a series of organizational and identity crises; as the civil society was growing more complex, and many projects and organizations from the AWC core became independent, so the need for the AWC as a network ceased to exist. After a long period of inactivity, the last assembly was held in 2006.

Documents from the AWC archive also show how extensive and active the correspondence was, and how strong the network was among similar initiatives at the local, regional, and European level. In that sense, the Anti-war Campaign was part of a trend that was taking place all over former Yugoslavia, indicating the awareness for the need for action and cooperation in the collective space. So, it is possible to find a series of notes and letters from associations in Slovenia, Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia. The catastrophe which followed, first the outbreak of the war in Croatia, then in Bosnia and Herzegovina, violently ended many of those connections. The inventiveness of the AWC was reflected in the early use of electronic communication: the first modem in an office in Zagreb was installed in early 1992. Networking was a condition for survival.

The challenge we face today is that thirty years ago can no longer be recalled from random access memory, albeit deserving to be called memory in the full meaning of the word. Today, the reconstruction of the institutional memory requires digging through various archives. A great part of the records which made up the AWC office in Zagreb as a service of the entire network is now held in the Documenta. Most of the digital records from the late ’90s and early 2000s are lost forever, due to major changes in technology as well as proverbial negligence and ignorance about the importance of preservation. Vivid memories of the actors from that time are a great support, but the availability of these witnesses will eventually decrease. This segment is immensely important because even if written sources exist, they reveal only one dimension of communication.

Communities of researchers have already saved a part of that heritage by turning them into a series of professional and scientific papers, master’s and doctoral dissertations and books. Despite the fact that the themes of peace action are still too alternative for the public and school curricula, points of entry and deconstruction of national canons still exist. But even more important is the question as to which communities will continue to inherit as successors the traditions of anti-war and peace movements and their resistance and rethink them. The need for this undoubtedly exists when we see the extent to which our societies have not yet worked out the experiences of war, which still haunt them. To that extent we can still see the relevance of the AWC Charter.

Nikola Mokrović (1983), was born, lives and works in Zagreb. He has a degree in political sciences. Since 2010 he works at Documenta – the Center for Dealing with the Past, on the protection and digitization of materials created by the work of civil society organizations and independent culture, and on the project “Human losses in the war in Croatia 1991-1995.”

[1] Anti-war campaign 1991 – 2011 Untold history (Anti-war campaign and Documenta, Zagreb 2011)