By Refik Hodzic, ICTJ

“We’ve gotten used to the conflict; and that habit has created a vicious situation in which many prefer the certainty of war – with its clear rules and predictable risks, with the dead being a burden for others, with its hate routines and well-defined enemies – than the uncertainty of peace. The decision ahead of us, the citizens, will demand unprecedented responsibilities from us. The main one, maybe, will paradoxically be the easiest: to inform ourselves well. For that we will have to search – within the tangled mess of the right’s demagogy and the populisms of the left – the scarce resources of truth, judgment and magnanimity. For now, I hope that we measure up to the moment.”

These words from Colombian writer Juan Gabriel Vásquez were published recently in a text which considers the historical opportunity presented to the people of Colombia in the upcoming plebiscite on the peace agreement between the government and FARC rebels. They capture brilliantly the struggle in societies dealing with legacies of conflict or violent state repression to mobilize informed citizenry to stand up for truth and victims’ rights, to make informed judgments on how to deal with the past, and disentangle the facts from the sticky web of political rhetoric, denial, and polarizing propaganda. This struggle for informed citizenry crucially depends on the direction taken by one key agent of social change – the media.

Transitional justice measures signal a shift of values dominant in a society – from an environment in which no person is safe if they belong to a targeted group, to a sustainable peace and a system of values in which the rule of law is respected and citizens trust the state to be a guarantor of their rights. There is no magic bullet to make this shift happen overnight – it usually takes years, if not decades, to unfold and must often take root in deeply polarized societies, where trauma and mistrust shape public opinion.

In such circumstances media reporting does not simply present the facts, but instead shapes the parameters for interpreting divisive political issues. Coverage in such polarized contexts can mitigate or obscure the substance of transitional justice efforts to establish what happened, who the victims were, and who was responsible for the violations. It can either catalyze or paralyze the debate on how to repair victims and ensure that systematic violence does not recur.

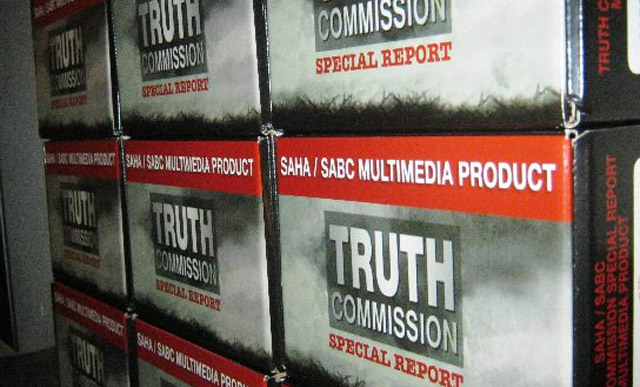

This relationship between media and transitional justice efforts is delineated by two diametrically opposed manifestations: symbiosis and conflict. There are countless examples of media projects that have been crucial in promoting victims’ rights, championing accountability, and even catalyzing transitional justice processes by uncovering hidden truths about crimes and their perpetrators. In South Africa, the media played an instrumental role in the early successes of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. On the other hand, the examples of Peru, countries of the former Yugoslavia, and numerous other transitional contexts show that media has often played a decisively negative role in mediating information about war crimes trials or truth commissions, often cementing public misperceptions and fueling political polarization in already-fractured societies. Such negative impacts often stem from the politicization of coverage, the ‘us-versus-them’ narrative, and some journalists’ inadequate knowledge of procedures and legal concepts.

However, transitional justice practitioners must shoulder their share of responsibility for this troubled relationship. Transitional justice institutions often see media not as an ally but as an ill-informed nuisance, if not an adversary. The philosophy of ‘our work speaks for itself’ permeates many a courtroom and office staffed by those whose decisions could irreversibly shape societies’ ability to reckon with a violent past. In some cases, the furthest they go in ensuring a social impact of transitional justice work is to task special offices with public relations under the guise of ‘outreach’, while the idea of working with media to ensure this broader impact is reduced to organizing ‘trainings’ and ‘education seminars’ for reporters.

Such outreach efforts often amount to no more than “public relations by other means” and do little to create a genuine sense of ownership among the key constituencies of transitional justice – victims, civil society, policy makers and broader public. Without active participation of media as agents of social change fully aware of its impact, that sense of ownership will remain elusive even with the most sophisticated outreach effort. At the same time, the media must accept that undermining transitional justice processes is not compatible with the proclaimed underlying principle of journalism: acting in the interests of the public.

Furthermore, in places where media ferment violence and contribute to the dehumanization of the other, the reversal of dominant media narratives offers the key to shifting public dialogue from denial to acknowledgement. Such work must feature voices of victims which serve to humanize them again, and to demonstrate that empathy for the other is not an act of betrayal of the dominant group. Again, the break with the past signaled by transitional justice measures must be communicated by the media if it is to be fully embraced by the polarized populace.

Arriving at a collective memory of the past is one of the greatest challenges facing a post-conflict society because it implies reaching a degree of consensus in a polarized context. While truth commissions attempt to present an objective account of a society‘s repressive or violent past, they inevitably contend with multiple perspectives and interpretations of this history. In essence, truth commissions and other transitional justice mechanisms must mediate this conflict to bring society to a shared version of this past, which often entails a society-wide admission that egregious human rights violations occurred and that victims must be acknowledged. However, to generate such an admission, transitional justice efforts rely on the media to encourage consensus-making about the past—a daunting task.

What does this mean in reality? If the goal of all the various mechanisms of transitional justice is to impact people’s lives for the better, media’s role in sharing information and shaping debate must be intentionally incorporated from the very beginning. How to do this and what it would look like, however, are questions still largely unexplored both in practice and in the academy.

Drawing on academic work on the subject and the voices of journalists, transitional justice practitioners, and academics, David Tolbert and I tried to chart the ways in which the media can impact the success of transitional justice efforts and examine some factors shaping journalists’ approach to reporting on these processes. We brought the voices from the rich debate on the role of journalism in transitional justice to briefly analyze the distinct ways that media cover or interact with transitional justice processes during their various stages and examine some examples of different forms of symbiosis between media and transitional justice processes. The discussion of the complementarity between the two is followed by examples of the destructive impact of politicized media coverage, which has seriously undermined the work of truth commissions or trials in certain countries, diminishing any lasting societal impact they might have. Finally, the paper draws attention to the possible benefits that emerging transitional contexts like Colombia could experience from understanding the significance of this complex relationship and addressing the need for a constructive engagement of media in the transitional justice process from the beginning.

In writing this paper, we never intended to offer definitive answers to many questions that burden this largely unexplored relationship that so significantly impacts transitional justice efforts. Instead, we hope to catalyze further debate on the crucial role of media, to try and bridge the gap between journalists and transitional justice practitioners, to reduce mistrust as much as possible, and ultimately to turn the flickering instances of symbiosis between media and practitioners into a consistent reality.

(Published on ICTJ, 20.09.2016)