Over the centuries, Skopje has been an important cultural and historical center in its geographical environment. Its growth and significance continued unabated until its zenith, when the city was razed to the ground by Austrian General Piccolomini in 1689, derailing it from its development trajectory. At that time, Skopje was said to be a city the size of Prague, with cobbled streets of white cobblestones, more beautiful gardens than Rome, causing astonishment with its beauty, but also true pain to the general who had to burn the city because of cholera.

Even the constant wars and conquests, invasions and devastating earthquakes of 518 and 1555 did not stop its return to the significant position. But, the fire from the end of the XVII century separated its continuity with a 200-year lull, until the second half of the XIX century when its new resurrection begins, only to increase its development by several times during the XX century.

The culmination of the actions strengthened the position of the city as an important center, capital of provinces in foreign kingdoms, but also established it as the capital of the modern Macedonian state. The twentieth century did not spare the city at all from the temptations of human aggression and natural disasters, of which the earthquake of 1963 dealt the greatest blow.

What showed maturity in such turmoil was the urbanism that managed to define a city in which we recognized layers of ancient, medieval, oriental, European, modern and contemporary. Of course, there is room for several dilemmas about the post-earthquake reconstruction where the eclectic city was not valued enough, but the compromise and new actions were so significant that Skopje was the center of architectural and urban trends for several decades.

What happened next?

The 90s came, the disintegration of the powerful federation and the separation of the Macedonian state into an independent state. It represented a period of transition, in which social and common values were scorched by negligent capitalism. Greed had befallen individuals, fast-growing businessmen, political camps and ethnically immature organizations that had created a chaotic society of power-sharing and plunder of governing territories.

The result was the institution the City of Skopje and 10 municipalities that have different competencies, which belong to different political agendas that have no contact with the essence of urbanism and architecture. It all comes down to survival (with certain exceptions), without the visions we had just 50 years ago.

The last mass and visible aggression was the project “Skopje 2014”, as a phenomenon that went beyond professionalism, mixing all the speeds of goodwill, romanticism, nostalgia and abuse of power, creating a perfect distraction from other parts of the city, which was completely immersed in an urban autoimmune disease (partitioned balconies, outbuildings according to individual wishes, etc.).

Historical axis North – South

Oriental and medieval Skopje had at its center what we recognize today as Bit-pazar. It is the plain between the two hills, on one side Gradishte, where the Skopje Fortress is located (from the VI century in continuity) and the Virgin Hill, on the other side.

The famous monastery “St. George” was located here, on top of which the Sultan Murat Mosque was built in 1436, and in whose yard a century later, between 1566 and 1572, the Skopje Clock Tower was erected on the site of one of the fortification towers.

Starting from this point, as a point in space, passing through the market that has a 10-century old tradition, the Old Skopje Bazaar, which existed at the same place in the Byzantine period, through the grand Stone Bridge (built on VI century foundations), then through the central Skopje Square and once the most important city street, as urban movements of European Skopje, the axis was created that ended with an exceptional point in the symbol of the pre-earthquake city – the Old Railway Station, today the Museum of the City of Skopje.

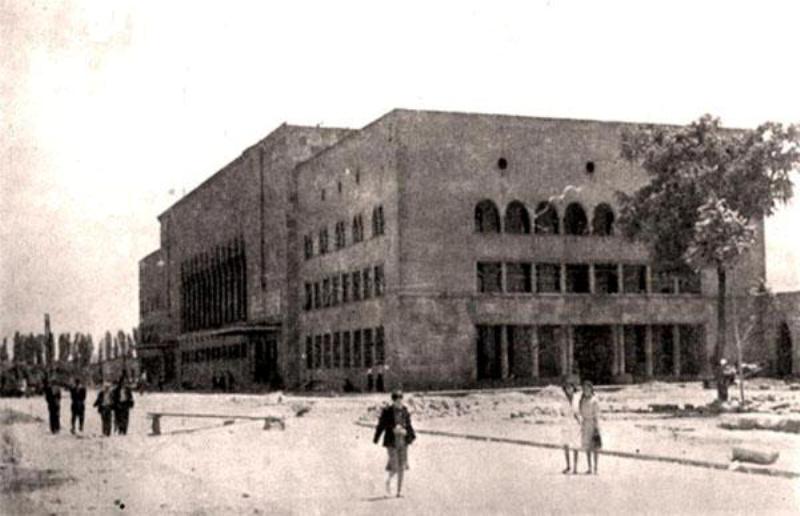

The railway station was defined as an urban position in 1873, when the railway Skopje-Thessaloniki and Skopje-Mitrovica were opened, while the building, whose remains still exist today, is the work of the architect Velimir Gavrilovic, built between 1931 and 1940.

These two points, as the starting and ending point, are extremely important architectural-urban positions, with living and authentic buildings from different times. The axis is the approximately 2 km long pedestrian zone, uniting the two banks of the city across the river Vardar, through a story of cultural heritage and space that develops throughout a millennium.

Both points are attacked by ignorant urbanism that completely ignores their significance, their testimony, throwing them at the mercy of investors, as the authorities have proved unworthy and without vision to manage these areas.

The clock tower

Moving from the city center to Bit Pazar, you stop in the center where your glance stops at the hill, whose dominant is the Clock Tower. This is the last point you can reach with the view, while as a visitor it would be your final destination.

Its position has made sense ever since the past, that is the point of space, while the clock is the one that determined the time for trade, for meeting, for marking the beginning and the end of the workday. This says that the main purpose of that object is its overhang, its visual and sound reach.

But, the Macedonian urbanism of today foresaw buildings at the foot, with the main treatment on the boulevard front. The height of these buildings takes away the view of the Clock Tower and completely ignores its significance, both historically and functionally. After all, the ordinary and casual passer-by may never find out about its existence.

The old train station

At the opposite end of the axis, the space united several segments – the Museum of the City of Skopje, a wing of the former railway station, porch and portal, as a memory gesture of the central vessel of the building, platforms where several wagons were converted into restaurants, nightclubs and car parks. This space had always been thought of as a complex and indivisible whole, in fact it is the surface where the station once existed in its entirety. One of the most reasonable competitions on the topic “City House” was organized for this space in the 90s of the last century, which had the idea to be included in the missing part of the building. Of course, it remained only on paper.

This building has special architectural values and special significance in the city’s history. It was talked about with admiration, while the mural was positioned in the hall, as one of the most significant achievements of the Macedonian cubist Borko Lazevski.

The Museum of the City of Skopje has been a symbol of the catastrophic earthquake for the past half century and a monument to the difficult struggle of the city-Phoenix. At the same time, the institution of the City of Skopje and the Municipality of Centar, which bears the symbol of the phoenix bird on its back, allowed the humiliation of this building. In the near future it will be embraced on all sides by a shopping mall, as a true symbol of capitalism and private interests above the societal.

With the realization of the project of Limak, or the complex “Diamond of Skopje”, a precedent was set in the shaping of the plots, which allowed for the fragmentation of the whole and the potential of the space and what is most shameful, allowed the demolition of the platforms and original parts of the train station building, which also had a protected status.

Practically, the institutions led by any and all political camps show immaturity for all topics with respect to cultural heritage, architectural valuation of the space and the duty of urbanism as a starting point for spatial planning. At the same time, in the continuum of civilization we have proven ourselves as unworthy and below average generations, i.e. the weakest link. Goodbye!

Filip Konevski is born in Skopje in 1987. He graduated at the Faculty of Architecture in Skopje on the topic “Institute of conservation and restauration”, while at the moment he works on his master’s degree “Active approach towards architectural heritage”. His working experience includes architectural, handcraft and art studios. In addition to founding MARH and managing the site, he is currently employed in a design studio in Skopje. The rest of the time is dedicated to several areas in the field of creation, while in his home sphere (architecture), Filip acquired individual and group awards in domestic and international competitions.