Source: Recom.link

Photo: Alija Izetbegović, center, president of Bosnia and Herzegovina, looks on as Franjo Tudjman, right, president of Croatia, and Slobodan Milošević, president of Serbia, shake hands after initializing a peace accord between their countries during the Dayton Peace Accords of 1995. (John Ruthroff/AFP/Getty Images)

By Gerard Toal and John O’Loughlin, Washington Post

Last November and December, a series of events and conferences marked the 20th anniversary of the Dayton Peace Accords of 1995, the negotiated agreement that ended the Bosnian war and devised a complex governance structure for the country.

The Dayton agreement was not a democratic agreement. It was not even an agreement negotiated by Bosnians or written in Bosnian. Pushed by the U.S. and European powers, the agreement between the authoritarian presidents of Croatia (Franjo Tudjman) and Serbia (Slobodan Milošević) carved up the territory of the third president in the talks, Alija Izetbegović of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH). His country was recognized as a unified state but divided 49 percent/51 percent into two ethnoterritorial zones, a Republika Srpska for Bosnian Serbs and a Bosnian Federation for Bosnia’s Muslims (Bosniaks) and Croats.

For victims of ethnic cleansing and genocide, which had recently occurred in Srebrenica, the peace was bitter. Many felt it was a win for perpetrators and criminals. The International Criminal Tribunal on the former Yugoslavia would later charge Milošević with war crimes and find Tudjman posthumously guilty of joint criminal enterprise in Bosnia.

But it was also a triumph of American diplomacy. Dayton gave Bosnia a chance as a state; it gave a younger generation the possibility of transcending the ethnopolitical divisions that had plunged it into war.

Twenty years later, what does Bosnia’s “Dayton generation” — those who were children or not yet born in 1995 — think about the agreement? How do their attitudes compare with the generations that grew up in Yugoslavia and lived through its collapse and the bloody war that followed?

Ten years ago, funded by the National Science Foundation, we organized a representative survey of 2,000 Bosnians, asking face to face how they felt about the Dayton Peace Accords and ethnic separation. Last month, 20 years on, we asked 3,000 people the same questions, again face to face.

Although we did not resurvey the same people we had surveyed in 2005, the large numbers in these demographically representative surveys allow us to track evolving attitudes in post-war Bosnia. Prism Research, a reputable Sarajevo-based research firm, conducted both surveys for us and the margins of error are less than 2.5 percentage points.

What do Bosnians think of the Dayton accord?

In 2005, we asked folks to choose among four statements about Dayton. Two were simple positive/negative reactions: “Dayton has been generally positive and should not be altered” or “… negative and should be abolished.” Two expressed other viewpoints also found in Bosnia: “Dayton was necessary to end the war but now BiH needs a new constitution to prepare for the EU” and Dayton was “an imposition of foreign powers.”

Not much changed in Bosnians’ attitudes to the Dayton Peace Accords between 2005 and 2015. The unqualified endorsement rose from 19.7 to 24.1 percent, the “necessary but” option rose from 47.5 to 50.5 percent, and the unqualified negative view was cut in half, from 10.8 to 4.8 percent. Those who thought of Dayton as an external imposition remained essentially unchanged.

Which ethnicity most highly approves of the Dayton accord?

Attitudes by ethnicity essentially stayed the same over the decade as well. As we explained in an analysis of our 2005 results, it was “indeed ironic that the greatest opponents to the implementation of the Dayton Peace Accords from 1996 onwards, the Bosnian Serbs, are now the community that view the agreement the most positively.” They did so because “Dayton legitimated Republika Srpska as an ethnoterritorial entity.”

By 2015, this attitude had deepened among Bosnian Serbs (as a previous post here explained). Fewer now echo the view of Radovan Karadžić, the Serbs’ wartime leader, that Dayton was an unwelcome imposed peace.

Bosnian Croats have shifted their attitudes significantly, from 43 to 57 percent for “necessary but” — and now hold that the Dayton framework needs to be updated. As a minority in the Bosniak-Croat federation, Croats feel aggrieved by their weakened political position and want a more favorable structure.

As the majority population now in the country — about 52 percent of the total — Bosniaks also want a restructuring of Dayton to institutions and political authority that reflects current demographics.

In the graphic below, we see that BiH remains ethnically divided in its attitudes over Dayton. Differences by gender, age, education and income levels within each group are not important since ethnic attachment overrides other factors.

Designed more to end war than to build a European state, the governance structures negotiated in Dayton are still in place. Only a minority of Bosnians approve of them — but right now there’s no good alternative that appeals to every Bosnian ethnicity.

The country remains poor overall, ranking 101st of 185 countries in GDP per capita, according to the World Bank’s 2014 figures. Ethnic differences are also evident. Bosniaks report the highest unemployment rate at 32 percent, while Serbs and Croats are at 27 and 25 percent, respectively. Serbs report significantly lower household incomes than the other groups at an average of $413 a month (converted at current exchange rates); Croat households earn $513 and Bosniaks $447.

Should Bosnia’s ethnicities be separated into different territories?

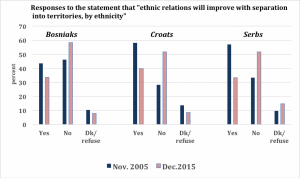

In 2005, we asked Bosnians if they agreed or disagreed with the following statement: “Ethnic relations will improve in my locality when all nationalities are separated into territories that belong only to them.” (In 2005, 50.5 percent of the sample said “yes”; at the time, we compared those results with attitudes in the North Caucasus of Russia, another former war zone, where less than 14 percent wanted ethnic separation.)

Here we have seen some important shifts in opinion. Fewer and fewer Bosnians — in all ethnic communities — support exclusive ethnic territories. Over 43 percent of Bosniaks supported ethnic separation in 2005; today that’s 33, a drop of 10 percentage points. Among Bosnian Croats, support has dropped from 58 percent to roughly 40, or 18 percentage points. The decline is strongest among Bosnian Serbs, with a drop from 57 percent to 33, or 24 percentage points.

Less-educated individuals in all three communities still prefer separation.

Has this drop come because of the attitudes of the “Dayton generations”? Let’s look at the graphic below, which shows various age groups’ attitudes towards ethnoterritorialism.

Our age categories have roughly equivalent respondent numbers in each. The youngest age group (18 to 35) in 2015 is the “Dayton generation,” ranging from those not yet born in 1995 to those who were 15 years old when Dayton was signed. This cohort shows the biggest differences from the attitudes of the young adults in 2005.

Far fewer young Bosnian Serbs of that age agree that ethnic separation is a good strategy than did 10 years ago, with a drop from 60 percent to 28, for a total of 32 percentage points. More Bosniaks in all three age groups disapprove of ethnic separation than did in 2005. However, as Bosnian Serbs and Croats get older, they grow more supportive of separating by ethnicity.

What does all this mean for Bosnian ethnic relations?

Overall, Bosnians are becoming less ethnoterritorial. Only 10 years ago, more than half the population believed that ethnic separation was the way to prevent conflict. And that drop isn’t just because a new generation is growing up in a less ethnically violent world.

Why then? Perhaps tolerance has increased as people have gotten used to dealing with other ethnic groups, especially those who have returned to the homes they were driven from during the war. After all, Bosnians have been traveling back and forth between the political entities without significant friction or dramas. Or perhaps ethnoterritorialism is already so widespread that, ironically enough, respondents feel it’s less urgent to say they want it. After all, it’s already the norm in most places.

To answer our question: Bosnia’s “Dayton generation” is the cohort least likely to support ethnic separation.

Here’s the most optimistic interpretation of this data: Attitudes in Bosnia are changing for the better — but institutions remain stuck in Dayton’s straitjacket, now two decades old.

Yet here’s the reality: Bosnia’s youths are very disengaged from politics. Seventy percent want to leave the country and only 15 percent think that they have any influence on governments.

Bosnia will apply for European Union membership next month. The prospect of E.U. membership, like the prospect of Bosnia again becoming a land of multiethnic tolerance, is far in the distance.

Gerard Toal(Gearóid Ó Tuathail) is co-author of “Bosnia Remade” (Oxford, 2011) and a professor at Virginia Tech’s campus in Alexandria, Va.John O’Loughlinis college professor of distinction and professor of geography at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

(Published in Washington Post, February 2, 2016)