Kosovo’s women help build a free Kosovo, so why does official memory still ignore them?

Prishtina, August 2023. A hot summer afternoon. I am sitting in a café across from a woman who made history. She is one of many who, in the ‘90s, organized the civil resistance against the Serbian regime, fighting for Kosovo’s independence. We smoke, drink coffee, and for three hours she tells me about the achievements of women during that time. She speaks of parallel education and healthcare systems, civil society initiatives, the documentation of war crimes at great personal risk, and a profound sense of solidarity. Her stories follow no chronology. They weave and overlap, reflecting the complexity of experiences that never found a place in official narratives.

Her stories echo a dozen other conversations I’ve had in Prishtina. I begin to see the city differently. Statues of armed men, street names honoring male heroes — where are the traces of civil resistance? Only the legacy of Ibrahim Rugova, founder and chairman of the Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK) and the country’s first president, seems commemorated, with bronze statues sparsely scattered throughout the city. There is no evidence of women. I realize this absence is no coincidence, but the result of a deliberate politics of forgetting that stretches far beyond Kosovo.

The West prefers historical amnesia

When I speak about my research in Germany, I am repeatedly asked the same question: “Why do you engage with this topic?” The implicit message is clear: what does this have to do with us? Isn’t this a matter of the past? Didn’t the NATO intervention in 1999 and the subsequent international engagement bring peace? These questions reveal an attitude that frames Kosovo almost exclusively through the lens of military intervention and international missions. I am determined to explore what lies beyond this narrow perspective.

Such reactions point to a deeper problem. Dominant narratives about Kosovo, shaped by buzzwords such as war, NATO and UNMIK, have created a hegemonic memory matrix that excludes everything that does not fit. Above all, they have silenced the perspectives of Kosovo Albanian women. International knowledge production has perpetuated a striking form of historical amnesia.

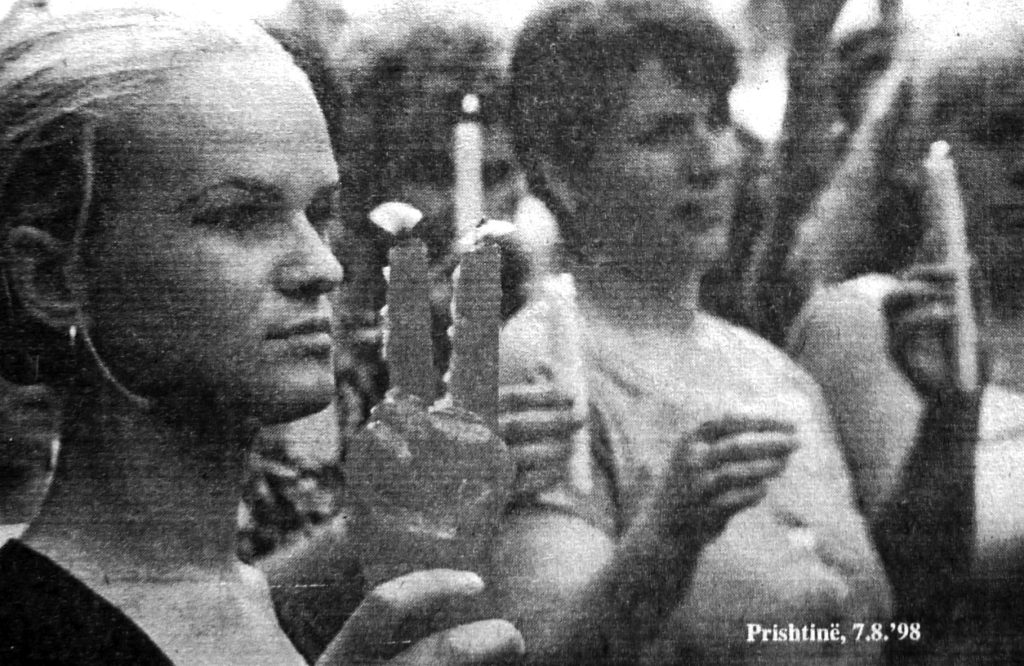

This amnesia dates back to the end of the Kosovo War and the NATO intervention of 1999, construed as the starting point of the country’s political subjectivity. What is systematically erased, however, is at least a decade of prior civilian resistance. During this period, Kosovo Albanian women not only built parallel systems with state-like institutions and structures but also established a civil society network. They organized protests that helped transform nonviolent resistance into a politics of bold and visible defiance, drawing international attention and accelerating the end of the conflict. This history, however, is relegated to the footnotes.

Flattening the past, controlling the future

Reducing Kosovo’s story to the war and the NATO intervention is not a habit of internationals alone. National memory practices also contribute significantly to this narrowing. In monuments and official historiography, the armed resistance of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) is heroized, casting (armed) men as the central figures of the struggle.

Should Kosovo Albanian women appear at all, it is in strictly binary terms: as victims of sexual violence or in their reproductive role as mothers. This reduction is not merely a local phenomenon, one that can be conveniently blamed on male local politicians, their patriarchal practices, or the gendered public sphere they occupy. On the contrary, it is part of a global structure of patriarchal memory politics.

The tendency to pathologize gender-specific hierarchies as a cultural trait of the “other” creates an artificial binary: on one side, the emancipated self of the West; on the other, the patriarchal “other,” in this case, the Balkans. In Germany and elsewhere, this helps conceal the omnipresence of patriarchal structures, shielding the West from self-scrutiny.

The “other” is granted little right to its own history. At the core of UNMIK’s statebuilding mission lay a “year zero” mentality: everything prior to the NATO intervention — Kosovo’s existing state, social, and political legacy — was to be erased. As Vjosa Musliu and Enduena Klajiqi observe: “The new future had its own activism, the right way of thinking about gender, the right way of thinking about emancipation, the right way of building a state.”

The message was clear: your decade of resistance? Irrelevant. Your functioning civil society networks? Backward. Your political visions? Incompatible with Western conceptions of statehood. This imposed ignorance prevented any critical examination of the past and created obstacles to the development of diverse, locally owned futures.

Kosovo’s women: doubly “others”

Unsurprisingly, this epistemic violence was disguised as progress. While UNMIK spoke of gender justice, women were relegated to sewing courses, confined to the private sphere. While invoking United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1325 on Women, Peace and Security, it distributed tractors to widows — on the condition that men be employed to operate them. The message was clear: you are recipients of our aid, not actors with agency.

This interventionist logic assumed it had “saved” women, even though women had organized and fought for themselves long before these interventions. It reinforced the binary coding of women as victims or mothers and systematically suppressed stories of women who acted beyond this framework.

This enforced disenfranchisement became particularly insidious when justified in the name of cultural sensitivity and notions of Muslim women. The claim was one of respecting “traditional culture,” but which traditions? Those of the 1990s, when women ran underground universities and documented war crimes? On the contrary, what was invoked instead was an orientalist fantasy of passive, veiled women, waiting to be saved by the enlightened West.

This characterization also legitimized the exclusion of women from political decision-making processes and erased their tradition of participation in formal politics. Their absence from these processes hindered the incorporation of women’s experiences into memory culture, an absence whose effects are still visible 25 years on.

Against this backdrop, UNSCR 1325 exemplifies the paradox of liberal gender politics. Rather than genuinely empowering women, it confined them to essentialist roles: as victims, mothers or bearers of a supposedly peaceful, conciliatory nature. Such sexist stereotyping relegated women to “appropriate” domains: ethnic reconciliation, yes; political power, no. In practice, the resolution functioned as an alibi, while the gender-specific concerns of women who had long been engaged in political work were sidelined and ignored.

Cynthia Enloe has exposed this tactic: “We will deal with gender later” is the eternal excuse of patriarchal systems. First, the state must be built; first, stability must be secured and the economy made to function; only then, someday, will gender justice be addressed. This strategy of delay allows the beneficiaries of patriarchal structures — both national and international — to consolidate their power. By the time structures are in place, positions allocated and history written, it is already too late for fundamental change.

We can face hypocrisy and reverse erasure

The systematic sidelining of Kosovo Albanian women’s contributions to nation-building and independence in the 1990s persists to this day. Women continue to be reduced to the roles of mothers and victims, remain underrepresented in the political sphere, and face ongoing economic marginalization. The complicity of international peacebuilding and national memory politics has not merely preserved patriarchal structures but actively reinforced them. Both sides have benefited from rendering female political subjectivity invisible: the international community by upholding gender-blind intervention models, and the national elite by consolidating male-dominated power structures.

The question “What does this have to do with us?” should be turned around. What does it say about us that we know so little of Kosovo’s stories — beyond war and military intervention, and especially of women — and rarely pause to ask why? That we overlook their systematic erasure, if we notice it at all, treating it as a local problem? That peace missions from the Global North replicate patriarchal structures while preaching gender justice?

Proclaiming a feminist foreign policy, as the previous German government introduced, is inherently contradictory when feminist movements in the very countries where Germany co-led international interventions are ignored.

From this perspective, the experiences of Kosovo Albanian women are not a distant case study, but a mirror of patriarchal memory politics, mechanisms that erase women from history everywhere, including in Germany. Engaging with this history doesn’t require exhaustive archives or academic study. Often, a conversation in a café, a few questions to one’s grandmother, or simply listening with intent is enough. These stories are not relics of the past — these women are still here.

Systematic forgetting is problematic, but not irreversible. Asking “Where were the women and what did they do?” is the first step toward challenging one-sided historiography. This is more than an academic exercise: it is an overdue contribution to a fuller, more accurate narrative.

When I think back to that August day in a café in Prishtina, to the hours spent listening to stories, it becomes clear that this woman was never invisible. She was made invisible by structures that disregard women’s voices: peace missions designed without local expertise, historiography that omits women’s accounts, and discourses shaped without women’s perspectives. Yet memories persist. The stories are there. What is needed is the willingness to listen.

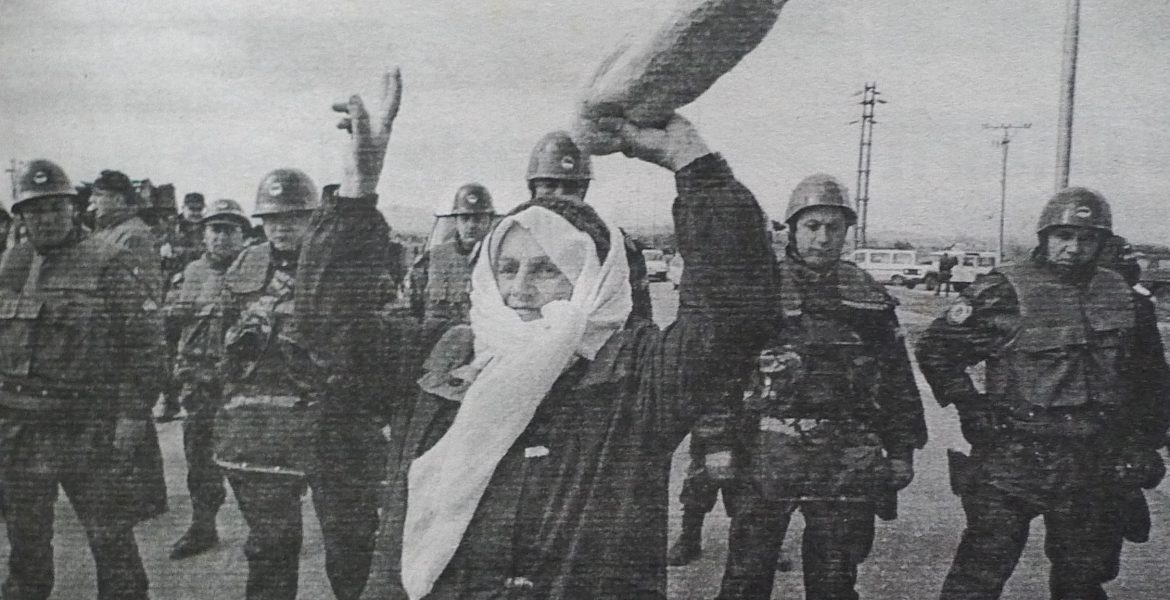

Feature image: “Bread for Drenica” protest, Koha Ditore, March 17, 1998 / Reuters (via National Library of Kosovo press archives).

Lea Hensch is a research associate at the Viadrina Center B/ORDERS IN MOTION in Frankfurt Oder and a project assistant at the NGO JustPeace in Berlin. A former intern at Pro Peace – Kosovo, Lea holds a Master’s degree in Social and Cultural Anthropology from the Free University of Berlin. In her Master’s thesis, Nation, Gender, and Memory Politics: The Forgotten Contribution of Women to the Building of the Kosovar Nation, she examined the role of Kosovo-Albanian women in the civil resistance of the 1990s, analyzing how the interplay between nation and gender shapes collective memory and narratives about women’s contributions to Kosovo’s independence.