Reaffirming Kosovo’s right to self-determination and independence

After Kosovo’s annexation by Serbia in 1912 and its subsequent involuntary incorporation into successive Yugoslav states, Kosovo’s Albanian majority endured systemic political repression, widespread human rights abuses, apartheid policies, settler-colonial practices and economic exploitation. Although Kosovo functioned for most of the last century as a de facto colony of Serbia, it was never recognized as such due to geopolitical interests and outdated concepts in international law, particularly the United Nations’ (UN) 1952 Blue Water doctrine, which defined colonies as overseas territories separated from their administrators by water.

This legal framework was established in the aftermath of World War II, when the UN was founded with the aim of preventing global conflict and maintaining international peace and security. Ratified on 24 October 1945, the UN charter enshrines self-determination, human rights and fundamental freedoms for all. Since its founding, the charter has facilitated the independence of 80 former colonies. This reached its height in the mid-20th century, as a wave of decolonization swept across the Global South, resulting in the establishment of new UN member states.

In the organization’s history of decolonization, the Blue Water doctrine was an early definition adopted by UN Resolution 637. The restrictive legal framework of this resolution failed to address instances of internal colonialism – situations where dominant ethnic or national groups within countries impose alien rule on other communities within state borders, subjugating and exploiting occupied lands as colonial possessions.

As a result, the international community overlooked Kosovo’s colonial status, even during the mid-20th-century wave of decolonization. It continues to do so today, eight decades later, despite developments in international law that recognize colonialism as not defined by geography but also by domination, subjugation and the denial of self-determination.

Meanwhile, Serbia maintains its claim over Kosovo, despite the recent atrocities it carried out in 1998-1999, which resulted in mass killings, systematic repression and the displacement of nearly a million Kosovar Albanians. Kosovo’s 2008 declaration of independence affirmed its right to self-determination. Yet more than 16 years later, Kosovo and Serbia are expected to “normalize” relations under the EU-mediated dialogue, a flawed process that has been at a standstill and avoids addressing the root cause of the conflict: Serbia’s colonial past and ongoing refusal to recognize Kosovo’s sovereignty.

Understanding Kosovo’s case through the lens of anti-colonial liberation and developments in international law might allow its right to self-determination to assume a different legal and normative weight. If Kosovo were recognized as a former colony, Serbia’s persistent claims of historical and territorial entitlement, particularly the Serbian national myth that Kosovo represents the cradle of Serbian identity, would be undermined.

This re-evaluation would enhance Kosovo’s legal and moral standing in its dialogue with Serbia and provide a stronger foundation for seeking broader international recognition, including UN membership. Moreover, this shift may place pressure on the international community to reckon with the inconsistencies in its application of decolonization principles.

The Blue Water Rule: A flawed colonial criterion

Serbia’s rule over Kosovo bore all the hallmarks of colonial domination: violent repression, alien governance, economic exploitation, settler colonialism and demographic engineering. But, because Kosovo was not an overseas territory, it was never recognized as such under the UN’s early decolonization framework, shaped by the Blue Water principle. Under this narrow lens, Kosovo could not be added to the list of Non-Self-Governing Territories under UN Resolution 1541; consequently, it remained outside the UN decolonization process.

UN Resolution 1541, adopted on 15 December 1960, defines a Non-Self-Governing Territory as a territory whose people have not yet attained full self-government and remain under the administration of an external power. The resolution identifies forms of control that limit political or economic autonomy, reaffirming the inalienable right of all peoples to self-determination. More importantly, it provides a legal grounding for decolonization efforts. Currently, 17 territories remain on the UN list of Non-Self-Governing Territories, including: American Samoa, Anguilla, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Falkland Islands (Malvinas), Gibraltar, Guam, Montserrat, New Caledonia, Pitcairn, St. Helena, Tokelau, Turks and Caicos Islands, United States Virgin Islands, French Polynesia and Western Sahara.

The debates preceding the Blue Water doctrine were pivotal in defining the geographic limits of decolonization. Prior to its adoption in 1952, a key point of contention had arisen from Belgium’s proposal to extend the right to self-determination to include “internally colonized peoples” and ethnic groups within contiguous sovereign states. Powerful member states, which had significant indigenous or minority populations, resisted this expansion, fearing it would legitimize secession and threaten their territorial integrity.

In response, the Blue Water doctrine, alternatively known as the Salt Water Thesis, emerged as a strategic legal and political instrument within the UN, narrowly asserting that only territories separated from the administering state by “blue water” (i.e., an ocean) qualified as Non-Self-Governing Territories entitled to decolonization. Dominant in the 1950s and 1960s, this maritime-based criterion effectively shielded contiguous or internal forms of colonial domination from international scrutiny, ensuring that the subjugation of national groups and racialized minorities within sovereign states remained outside the formal UN decolonization framework.

Since the adoption of the Blue Water doctrine, the concept of self-determination and decolonization in international law has undergone significant developments. In 1970, UN Resolution 2625 marked a considerable step beyond this narrow definition by reaffirming the right and principle of self-determination in the context of decolonization. Unlike the maritime-based criterion that preceded it, UN Resolution 2625 prioritizes subjugation over geography, characterizing colonization by the absence of self-government, thereby recognizing forms of domination that do not fit the “overseas” model.

Shortly after this resolution passed, Namibia’s experience of South African administration further eroded the Blue Water doctrine. In 1969, following South Africa’s refusal to relinquish its League of Nations mandate over what was then known as South West Africa (Namibia), the UN declared its continued occupation illegal. The landmark 1971 NamibiaAdvisory Opinion by the ICJ affirmed that South Africa’s presence in neighbouring Namibia violated international law, enabling self-determination in situations of internal or contiguous colonial domination. Crucially, South Africa had argued that Namibia was not a colony but an internal territory integrated into its legal order, an argument historically advanced by Serbia in relation to Kosovo.

The cases of East Timor and Western Sahara further demonstrate the evolution of international law beyond the Blue Water Doctrine, which traditionally equated effective control with sovereignty. Indonesia’s occupation of East Timor following Portugal’s withdrawal in 1975, for example, was never recognized by the UN, which affirmed the territory’s status as Non-Self-Governing and emphasized the Timorese people’s right to self-determination under UN General Assembly Resolution 2625. The eventual independence of East Timor in 2002 illustrates the legal prioritization of self-determination over mere administrative or coercive control. Similarly, Western Sahara remains under the administration of neighbouring Morocco without the consent of the Sahrawi people. Both the UN and the International Court of Justice have reaffirmed that, in this case, sovereignty cannot be claimed through occupation alone –– listing Western Sahara as a Non-Self-Governing Territory.

Subsequent ICJ rulings have also expanded self-determination beyond the Blue Water doctrine. Such as the 2004 Wall Advisory Opinion in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, which found that Israel’s construction of the separation wall in the occupied Palestinian territory was in violation of international law; it violated the right of self-determination of the Palestinian people, breached international humanitarian and human rights law, and states were obliged not to recognize or support this unlawful situation.

These developments confirm that colonialism is no longer defined by distance but by political domination, economic exploitation and the denial of self-determination. Contemporary legal scholars, such as Thomas Grant, a UK-based expert in state-recognition and territory law — whose work addresses the legal status of territories under the UN Charter, its decolonization framework and how non-overseas territories may qualify as Non-Self-Governing Territories — has argued that in the absence of the Blue Water Rule, Kosovo would have qualified as a Non-Self-Governing Territory (a colony) under UN Resolution 1541, strengthening the argument that Kosovo’s independence rests on the principle of remedial self-determination.

The UN’s practice following the Blue Water doctrine, its legal arguments surrounding internal colonialism and global shifts in decolonization discourse, position Kosovo as part of a broader legal-historical argument, suggesting that Kosovo’s struggle for independence aligns with the UN’s evolving decolonization framework.

Realpolitik and international law: A double standard

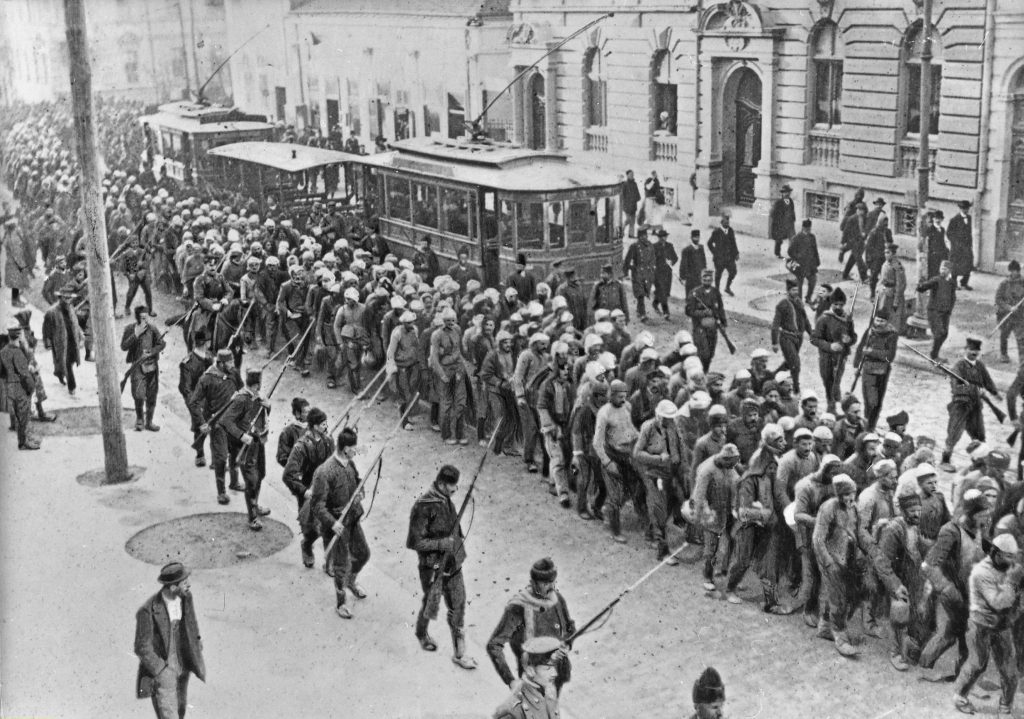

During the First Balkan War (1912–1913), Serbia’s unilateral annexation of Kosovo was marked by widespread violence. Serbian forces engaged in systematic attacks against the Albanian and general Muslim population in an effort to reshape the region’s demographic composition, as was documented at the time by Leon Trotsky and later by the 1914 Carnegie Endowment Report. Kosta Novaković, a socialist Serbian politician, also testified to the violent colonization and Serbianization of Kosovo, having witnessed it as a soldier of the Serbian expeditionary corps in the First Balkan War. According to his reports, 120,000 Albanians were killed in 1912-1913, with hundreds of villages bombed and burned.

Following the Balkan Wars of 1912–1913, which ended Ottoman rule in the Balkans, the international community’s selective acknowledgment of colonial histories became evident. Under the guise of a so-called civilizing mission, Kosovo was annexed without the consent of its Albanian majority by Serbia. The Great Powers — namely Great Britain, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Russia and Italy — confirmed Serbia’s claim at the 1912–1913 London Conference following these events.

The Conference recognized a reduced Albanian state (within its contemporary borders), awarding nearly half of its claimed territory, including Kosovo, to neighboring countries. The settlement reflected the realpolitik of great powers, imposing colonial rule on 40 percent of the Albanian population, who were excluded from the state of Albania. It also placed the Albanian-majority Kosovo Vilayet, previously an administrative region of the Ottoman Empire, under Serbian control.

In the years leading up to World War I, measures to establish Serbian colonial settlements in Kosovo began. The ‘Law-decree on the settlement of newly liberated areas’ was passed in February 1914, incentivizing settlement in newly annexed regions by promising substantial land allocations to incoming Serbian families, tax exemptions and free rail transport. The government even tried to attract Serbian emigrants from the United States to return and participate in the colonization of Kosovo.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Serbia continued to legislate colonial policies of land seizures and demographic engineering in Kosovo. In 1937, Vaso Čubrilović, a Serbian scholar who would later become a government minister in post-World War II Yugoslavia, presented an official memorandum, “The Expulsion of the Albanians,” which argued that the systematic ethnic expulsion and mass eviction of Albanians from Kosovo was a strategic measure of Serbian national interest. Kosovo remained under successive Yugoslav regimes throughout the post–World War II era, illustrating how diplomatic and geopolitical priorities obscured the colonial subjugation occurring within Europe.

In the mid-20th century, as the wave of decolonization throughout Asia and Africa led to the independence of 50 territories, Kosovo’s colonial status was consistently ignored on the pretext that territories adjacent to their colonizing state were integral parts of the colonizer’s state. The international community largely recognized Kosovo’s inclusion into Serbia and later Yugoslavia, but this recognition did not confer democratic legitimacy, as successive regimes maintained control through authoritarian means. As Robert Elsie, a renowned scholar of Albanian history, observes, “Vociferous claims emanating from Belgrade that Kosovo was ‘part of Serbia’ were notunlike protests in France in the 1950s that Algeria was not a colony but ‘part of France.’ In neithercase were the people of the territory in question ever consulted.”

Kosovo’s exclusion from global decolonization efforts did not mean that its subordination disappeared; it simply adapted to new political structures. Following WWII, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia became the Federal People’s Republic and later, in 1964, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. This period saw the promotion of a more open and federal system, which coincided with the adoption of UN Resolution 2625, as well as the broader geopolitical and ideological momentum of decolonization driven by the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), of which Yugoslavia, led by President Tito, was a founding member.

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), founded by states emerging from colonial domination, played a decisive role in shaping the United Nations’ decolonization agenda during the second half of the twentieth century. This commitment translated into a powerful, unified voting bloc within the UN General Assembly that unequivocally condemned colonialism, imperialism and neo-colonialism in all their manifestations, as well as lending consistent support for national independence movements. NAM’s collective advocacy accelerated the implementation of Resolution 1514 (XV), the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, by framing self-determination as a jus cogens (compelling law) norm, thereby creating the geopolitical and legal environment to empowered territorial entities, even those in complex federal structures like the one of its founding member states Tito’s Yugoslavia, to press for greater sovereignty and autonomy.

These global developments indirectly granted Kosovo a limited form of autonomy, which by 1974 had been recognized in the Yugoslav Constitution as an Autonomous Province. But this newfound status stopped short of recognizing Kosovo as an equal republic within the federation. Politically marginalized, it remained a de facto Non-Self-Governing Territory within a Serb-dominated federal order, subject to stringent control.

This unresolved status left Kosovo in a position of permanent subordination, where its autonomy depended entirely on the shifting political will of Belgrade. As Yugoslavia began to unravel in the late 1980s, Serbia moved swiftly to revoke Kosovo’s limited autonomy, reasserting direct control over Kosovo’s natural resources and suppressing political and cultural life. Throughout the 1990s, Serbia’s administration of Kosovo bore clear colonial hallmarks, marked by mass dismissals of Albanian workers, economic exploitation, the closure of Albanian-language schools and media, and a campaign of systematic repression. State-sanctioned violence escalated into widespread atrocities — killings, forced displacement and the destruction of villages — culminating in the 1998–99 war, which saw Serbian forces expel nearly half of Kosovo’s population and carry out mass killings that were later documented in war crimes trials. During the course of this war, over 13,000 people were either killed or disappeared.

In this context, the peaceful resistance of the 1990s, the Kosovar Albanian armed struggle of 1998-99 against systematic oppression and the right of Kosovo to self-determination through remedial secession from the Serbo-Yugoslav federation, were legitimate acts against an illegitimate regime, and consistent with international law, as was Kosovo’s subsequent declaration of independence.

Yet, despite this, Kosovo’s statehood did not emerge through a formal decolonization process. Instead, it was the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, NATO military campaign in 1999, launched to end Serbia’s ethnic cleansing in Kosovo, that brought an end to Serbian rule and paved the way for the people of Kosovo to determine their own future.

Regardless, Kosovo’s struggle for national liberation from Serb-Yugoslav rule was an attempt to break free from colonial domination within unequal political structures. Whether interpreted as a remedial secession outside the colonial context, as a breakaway colony of peoples under alien domination and occupation, or as a move toward external self-determination within the colonial situation, the recognition of Kosovo’s independence poses no threat to the stability of the international order. Quite the opposite, it is the ongoing undermining and denial of Kosovo’s sovereignty by Serbia, and the constant Serbian efforts to discredit and delegitimize Kosovo statehood, that really undermines regional security.

Challenging the rejection of Kosovo’s Independence at the International Court of Justice

Following nine years as an international protectorate under the United Nations Mission in Kosovo, UNMIK, Kosovo declared independence in 2008, following a series of UN-led negotiations chaired by former Finnish President Martti Ahtisaari and coordination with members of the international community. Within two years, 69 countries recognized Kosovo, despite Serbia’s ongoing efforts to lobby against its statehood.

On August 15, 2008, shortly following Kosovo’s declaration of independence, Serbia requested an advisory opinion from the ICJ on the legality of this declaration. In this context, the Blue Water doctrine –– historically invoked to limit secession –– reemerged as a point of legal reference. Despite the UN’s expanding definitions of colonialism, several states at the ICJ hearings argued that the right to self-determination applies only to overseas colonies.

In the absence of a colonial narrative, Serbia, backed by Russia, framed Kosovo’s independence as secession that violated Serbia’s territorial integrity and as a dangerous precedent that undermines state sovereignty and international order. They found receptive ground in like-minded countries at the ICJ, which invoked the absence of a colonial narrative to reject Kosovo’s independence, warning that the recognition of Kosovo would endanger their own domestic interests.

Spain was one of the most vocal opponents of Kosovo’s independence before the ICJ, insisting that international law does not recognize the right of unilateral secession for regions within established states, except in cases of colonial rule or foreign occupation. It argued that Kosovo’s situation did not fall into either of these limited categories. Russia also maintained that international law forbids secession outside the colonial framework, warning that it might be a destabilizing precedent. Venezuela and Burundi echoed similar points, explicitly limiting self-determination to former and present colonies. Belarus adopted a slightly narrower formulation, allowing for secession only in colonial settings or under conditions of extreme oppression.

The nations that supported Kosovo’s declaration at the ICJ centered their arguments around three principal legal rationales. Albania, the United Kingdom, Norway, Estonia and Poland explicitly relied on the argument of remedial self-determination, contending that prolonged repression and the denial of meaningful internal self-government made unilateral independence a last-resort remedy. Ireland and the Netherlands advanced positions closely aligned with this, stressing the exceptional humanitarian and governance deficits in Kosovo. The remaining supporters, the United States, France, Germany, Denmark, Austria, Slovenia, Switzerland, Japan, Czech Republic, Finland, Luxembourg, Latvia, Maldives and Sierra Leone emphasized alternative grounds: some stressing that general international law contains no prohibition on declarations of independence, others characterizing Kosovo as a sui generis case arising from long UN administration under Security Council Resolution 1244.

In 2010, the ICJ delivered an advisory opinion stating that Kosovo’s unilateral declaration of independence did not violate general international law. It also concluded that Kosovo’s declaration did not breach Security Council Resolution 1244 –– which had established the United Nations’ Mission in Kosovo, UNMIK, in the aftermath of 1999 –– since this resolution had not defined Kosovo’s final status; and the Security Council had not reserved for itself a decision on it. At the time of the ICJ hearings in December 2009, around 69 countries had recognized Kosovo’s independence; this number continued to grow after the court’s hearing.

Although supporters of Kosovo’s independence have described its case as sui generis, its true uniqueness stems from its colonial past, an aspect often neglected in international legal and political discourse, as illustrated at the ICJ, where opposing states invoked the exception of a colonial context when rejecting Kosovo’s independence.

Despite this ruling, countries such as Spain and Russia continue not to recognize Kosovo, citing the same arguments. Seventeen years after declaring independence in 2008 and following the recognition of 120 countries, Kosovo continues to struggle with contested legitimacy and a stalled normalization process in its dialogue with Serbia. Its membership in the United Nations also remains notably obstructed.

Meanwhile, Serbia’s colonial ambitions have persisted even after Kosovo’s 2008 independence and the ICJ’s 2010 confirmation of its legality. Belgrade continues to maintain parallel structures in the Serb-majority north — running schools, hospitals, municipal administrations, security coordination and direct financing — creating an alternative system that undermines Kosovo’s institutions while exerting control over local political life by selecting, funding and directing Serb representatives. Ongoing efforts by Serbia to partition northern Kosovo, which by no coincidence encompasses key natural resources, include establishing a self-serving association of Serbian municipalities, and orchestrating or enabling violent terroristic attacks — such as those in Banjska (2023) and on the Iber-Lepenc canal (2024).

With this in mind, Kosovo should draw attention to its colonial past, informing Spain and like-minded states that obsolete interpretations of colonialism skewed the ICJ debate. The 2008 declaration of independence was not merely a unilateral secession, but a remedial exercise of self-determination against colonial domination — similar to Namibia’s under South African rule. Had the Blue Water Rule not applied, Kosovo would have qualified as a Non-Self-Governing Territory, effectively a colony under UN Resolution 1541. This classification would have placed Kosovo within the UN decolonization framework, affirming its right to external self-determination.

Positioning Kosovo within this colonial paradigm suggests that its struggle is not merely one for the recognition of its statehood in accordance with the ICJ advisory opinion, but for the acknowledgment of its colonial past and its rightful place within the unfinished global decolonization process.

This approach underscores the moral imperative of decolonization, bolstering Kosovo’s claims to sovereignty and opening diplomatic opportunities by fostering solidarity with postcolonial nations. Such an approach would enable Kosovo to build solidarity and draw support from former colonies in Africa, Asia, the Pacific, the Middle East and Latin America. It also provides grounds to challenge the positions of countries that, in principle, have historically endorsed the UN decolonization process and the independence of former colonial territories but have cited the absence of a colonial context when rejecting Kosovo’s independence at the International Court of Justice.

While acknowledged throughout the years by Albanian, Serbian and international scholars, intellectuals, politicians and diplomats, Kosovo’s colonial past gained new significance following the United Nations Security Council briefing on 8 February 2024. Kosovo’s delegation formally raised the issue of its colonial past in the session on the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK), marking a significant moment in foreign policy discourse and offering hope for a shifting narrative that will finally address this legacy.

The state of Kosovo is currently compiling evidence and preparing a case to seek official recognition of these events as genocide through established international legal mechanisms. In June 2019, the Kosovo Assembly approved a draft resolution demanding justice for 186 massacres committed by the Yugoslav Army, Serbian police and paramilitary forces during the 1998-99 war in Kosovo. It also called for the establishment of a new tribunal to prosecute crimes against humanity and genocide against ethnic Albanians during the war.

Within this context, Kosovo’s experience of Serbian colonialism is not only a matter of historical justice and accuracy, but also a critical factor in shaping its current political status and future diplomatic trajectory. Recognizing Kosovo’s colonial past is essential for strategic diplomacy. It challenges the prevailing narratives that obscure the asymmetric power dynamics between Serbia and Kosovo, and argues for the centrality of colonial framing in redefining the terms of engagement in the region.

These narratives have long served as ideological tools to legitimize political control. Acknowledging this history exposes Serbia’s claim over Kosovo as being colonially motivated rather than legally or morally grounded. Beyond historical clarity, the colonial framework has tangible implications for ongoing negotiations and international diplomacy.

A sustainable and genuine normalization process between Kosovo and Serbia cannot occur without Serbia acknowledging the colonial nature of its past governance over Kosovo. Continued denial serves only to reinforce nationalist and clerical narratives within Serbian society, which — often amplified by Russian geopolitical interests — undermine regional stability and obstruct meaningful reconciliation. As a result, Serbia needs to be constantly reminded about its prevailing collective amnesia and its century-long colonial treatment of Kosovo.

Deconstructing Serbia’s entrenched colonial mentality is essential not only for safeguarding Kosovo’s sovereignty but also for preventing the perpetuation of historical injustices. This colonial context must be elevated from rhetorical appeals to a central component of the political, legal and diplomatic efforts aimed at resolving this deadlock. Addressing this dimension openly and systematically can help reorient the Kosovo-Serbia dialogue toward a future rooted in equity, accountability and mutual recognition.

Feature image: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0

Fatmir Zajmi was a member of the first generation of career diplomats of the Republic of Kosovo, having previously served in missions in New York, Paris and Budapest. Over the years, Zajmi has published articles on this subject matter in Kosovo and abroad. The subject of Kosovo’s colonial past is explored in his forthcoming book.

The stances and views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the positions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Diaspora of the Republic of Kosovo.

This article was originally produced for and published by Kosovo 2.0. It has been re-published here with permission.