When women rule, peace lasts – this is what speakers at international conferences often say when talking about gender issues and peace. But in practice, neither women rule (given their low representation in politics), nor is peace lasting. We are witnesses to the constant outbreak of conflicts in different parts of the world, and in each of them the greatest victims are women and children. The world organization recognized the need to create a framework that would ensure the inclusion of women in peace processes and would lead states to find mechanisms for preventing and countering the consequences of military conflicts. Therefore, in October 2000, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 1325, which requires all actors in conflict to include a gender perspective. This Resolution is based on four main pillars: Prevention, i.e. a focus on preventing sexual and gender-based violence and awareness of gender equality in conflict prevention and early warning systems. This includes preventing sexual exploitation by soldiers and prosecuting perpetrators; Protection, which refers to promoting women’s safety, physical and mental health, economic security and legal protection; Participation, which means increasing the number of women in peace processes and at all levels of institutional decision-making, including in UN bodies; and Relief and Recovery, which should provide rehabilitation, reintegration and post-conflict addressing the specific needs of women and girls. The UN has also established an Inter-Agency Working Group on Women, Peace and Security, led by a Special Adviser on Gender Issues, to ensure that all member states take steps to implement these practices.

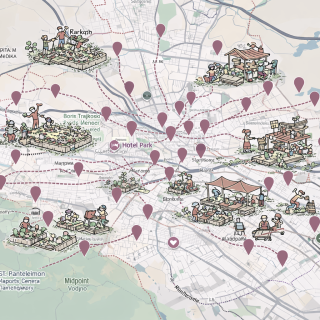

For years the Balkans had been inflicted by bloody wars and conflicts that have left deep traumas on the peoples living here. Faced with the challenge of restoring stability, the economy and infrastructure, but also of changing the collective consciousness, the Balkan countries in the post-conflict period have experienced profound social, political and institutional transformations. However, two and a half decades later, the desired change has not been achieved in several segments. North Macedonia, Serbia, Kosovo, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro ratified the UN Resolution and prepared National Action Plans. Later, they did the same with the 2011 Istanbul Convention of the Council of Europe, which is also an important international instrument for prevention and combating violence against women and domestic violence. In the meantime, each of the countries has been working on additional legislation to harmonize with these international norms, and the civil sector has been active and supported by the international community, which has further increased the pressure on the authorities. In the post-conflict period, addressing wartime sexual violence has become a central issue, particularly in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo. Pressured by from international organizations and survivors’ groups, Governments have introduced legal mechanisms to recognize rape victims as civilian victims of war. This recognition has enabled women to access financial compensation, health care, and social benefits. Specialist war crimes chambers and cooperation with international tribunals have contributed to the prosecution of some perpetrators, sending an important symbolic message that sexual violence will no longer be treated as an inevitable by-product of war. However, despite this progress, many victims still face stigma, social exclusion, lengthy legal processes, and limited access to justice.

The progress achieved by the Balkan countries is different in each country, but what all analyses note as a major problem in each of these countries is distrust in institutions.

North Macedonia has a Law on Prevention and Protection from Violence against Women and Domestic Violence that obliges institutions of the system to protect victims. The Law, adopted in 2021 and amended in 2025, assumes and strengthens the role of women within state institutions. Local shelters and support services have been opened and attempts are being made to provide safe houses for women and children victims of domestic violence. What international bodies note as the biggest shortcoming is the continuity, i.e. the lack thereof, and gaps in the implementation in terms of accessibility to services and, of course, the distrust in institutions.

Kosovo has been developing legal and strategic frameworks to align with the Resolution and the Istanbul Convention, including criminalizing domestic violence, but the first Law on the Prevention of Violence against Women and Domestic Violence was adopted in 2023 with the assistance of the OSCE. Kosovo is developing National Plans, but there is a notable lack of compliance with European standards, which is further complicated by the lack of formal membership in the Istanbul Convention. Mistrust in institutions exists, and trust is being gained by the non-governmental sector. Women’s NGOs are strongly committed to protecting women’s rights, working to confront the past, and providing services for women’s physical and mental health.

Serbia has National Action Plans, participates in international bodies and makes efforts to improve services, but still NGOs are proving to be more effective when it comes to women’s rights advocacy, but also to protecting and supporting women victims of sexual violence inflicted during war and gender-based violence. The OSCE in its research notes a consistently high perception of violence and low reporting rates – a consequence of distrust in the system. What stands out as particularly worrying is the insufficient capacity of the criminal justice system.

Bosnia and Herzegovina was the first country in the region to adopt an Action Plan following the Resolution in 2010 and has since implemented several generations of these plans. An Agency for Gender Equality has been established to lead and monitor implementation across the administrative entities. The action plans have contributed to increasing the number of women in the police, military and peace missions, but despite this progress, women remain underrepresented in leadership positions. What is perceived as a notable problem is the uneven implementation of protection services between entities and cantons.

Albania adopted its first National Action Plan in 2018 and has since been actively cooperating with international actors on strategies related to the protection of women and the fight against gender-based violence. The strengthening of this cooperation has been particularly noticeable in recent years due to the open path to the EU. Albania’s efforts have been noted when it comes to awareness-raising campaigns about the role of women. The biggest challenges, in addition to the distrust in institutions, are the shortcomings in the protection system. Despite the existence of the necessary legislation, social services do not meet the needs.

Montenegro has adopted several Action Plans in a row as well as the gender perspective in its institutions, which has led to increased participation of women. However, despite efforts to achieve the same in the security system and peace operations, women’s participation in peace processes remains significantly low. The biggest challenge is the gaps in the implementation of the Action Plans, but also noted problems such as human trafficking, which require a connected and integrated system of bodies for legal reform to start yielding results.

The progress made by the Balkan countries is very significant, but not sufficient. Good legislation is not fully reflected in practice. Although the number of women in the armies has increased, there remains a large gap in leadership, that is, in the career advancement of women in security structures. Social stigma, patriarchal norms and political resistance limit the effectiveness of reforms, especially in rural areas and smaller towns. The biggest challenge for the Balkan countries is the system for protection from domestic violence, which is also reflected in the number of femicide cases that occur in the region. According to the analyses of the UN bodies, the Balkan “hotspot” is Serbia with consistently high rates of femicide, followed closely by North Macedonia and Albania. In most cases, the perpetrator is an intimate partner or family member. Non-governmental organizations dealing with this issue note that the nature of gender stereotyping and prejudice within institutions is very present, especially in the judicial system and in many cases stereotypical reasoning by judges has been observed. Strong political will, greater institutional efforts and collective maturation are needed to change these situations in the Balkans, otherwise, adopted Resolutions and laws will remain only as wishful thinking on paper.

Kristina Atovska