Can narratives of our connection with the earth lead to healing collective wounds? A meditation with the work of Albanian artist Silvi Naçi opens a portal to this possibility.

“We cannot give up writing stories about what it means to be human that displace those that are at the foundation of Empire…Now the question for academia in the 21st century is will you make space within it to be able to write a new foundation” — Sylvia Wynter, Human Being as Noun? Or Being Human as Praxis? Towards the Autopoetic Turn/Overturn: A Manifesto, 2007

“A new gesture, it creates new respiratory rhythms. The Fanonian fighter is a human who breathes anew, whose muscular tensions unclench, and whose imagination is in celebration.” — Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics, 2019

“…in these words of Kitsimba: ‘With careful attentive service and focused contemplation, the Divine is made manifest. It is why this work is never done.’ Thus, the cycle of action, reflection, and practice as Sacred praxis embodied marks an important reversal of the thinking as knowledge paradigm.” — M. Jacqui Alexander, Pedagogies of Crossing: Meditations on Feminism, Sexual Politics, Memory, and the Sacred, 2005

I grew up in a land close enough to be confused for home, yet far enough to never feel like it. My great-grandparents fled their homes in the violence that ensued post the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947. This stratification of the subcontinent was a direct consequence of the seeds of religious disquiet sown by British colonial rule, creating the largest forced displacement in history (estimated between 12-20 million people).

Its thorns haunt us unto today. The families I come from, like many others, left land and lineage behind in the province of Sindh, to travel by sea from Karachi to Mumbai. I grew up knowing the broad depersonalised strokes of this history, never peering into it long enough to catch a reflection of how deeply it was affecting me. Unmoored, without an ancestral archive beyond my great-grandparents. I eschewed their language to feel less like an outsider.

In this deficiency of tongue and ear, the emotional nuances of my grandparent’s stories, those that tell us who we are and where we ground ourselves, have been lost to me. It is only in hindsight that I see the ‘unrootedness’ that I wore with neoliberal pride was a growing abscess carved out of my sense of belonging. Detached not only from the earth, but also from my body, out of place in cis-heteronormativity.

Thus unrooted, first not wanting to know, and then unable to grasp, I was called to the work of Jamaican cultural theorist Sylvia Wynter, one of the foremost scholars of Black Studies and the colonial and postcolonial condition. In her pivotal formulation Being Human as Praxis, she urges us to reclaim acts of narrating our origin stories, as paths to destabilize the “overexposed” image of the White [and otherwise culturally dominant] cis-Man. Taking back agency for our stories to pass through our bodies and be transmitted on our own terms, we can “re-institute” ourselves as full and complex humans.

Under Wynter’s persuasion—reacquainted with my story, I listened for its traces, elusively moving through my body. Undervalued for decades, it was bereft of vitality. Creeping along haltingly, often losing steam or arriving at blockages. Tracing the veins of my narrative, certain nodes produced heightened affect. Sensitive, painful, throbbing, numb, or altogether missing.

Achille Mbembe writes of colonization as seeking to liquidate, “devalorize” or exoticise modes of relating, including, taking from Wynter, the stories we hold. Fissured, contused and de-membered, I read my story, my archive, as having been wounded by tactics of multiple oppressors—as well as my own acts in positions of oppression.

I propose, in the face of these sustained injuries, our wounded archives lose the ability to move, to circulate with their previous complexity, and/or are depleted of content and context, allowing narratives of the dominant class to infiltrate and assimilate them. To see the wound, acknowledge and know it is not an act of self-pity or victimisation. It is the impetus that enables us to orient towards the wound’s intrinsic capacity to move towards healing.

At the intersection of transness and dislocation, this wound feels much too large. Will it devour me whole? Chilean artist and poet, Cecilia Vicuna recalls an accidental amalgamation that results in the verb “to wounder“. I take her advice to make my way through, besides, caressing and teasing this energetic body. I wander with wonder to understand how others enter their wounds, I wander to the work of Silvi Naçi who first nudged me to Vicuna’s verbiage in ‘Language as Migrant’. As an artist of Albanian-heritage now living in Chumash and Tongva nation, colonized as LA, Silvi and I share many adjacencies of cultural vagrancy.

It surprised and delighted me to find a plethora of commonality between our regions in the short time I spent in Kosovo, at the invitation of Sekhmet Institute to curate the exhibition ‘Wrapped in the Shadow of Freedom‘. Tightly intermeshed familial and kinship networks—including a close eye on the affairs of your neighbours—alongside warm support in hard times and the omniscient yet somewhat distant role of religion were some of the parallels that I could quickly discern. Adjacencies that are stronger than either of our regions have to Europe.

The chance to cross oceans and listen, feel, and further narrate the adjacencies of cultures in previously colonized lands opens the portal for powerful decolonial alignments. To see ourselves connected beyond the word of power—in smells and tastes, in cacophony and care, in bonds formed on reliance and repair. I would be amiss not to mark here the complex ways in which colonization functions—also appearing in this particular constellation as India’s denial of the independent state of Kosovo, from the fear of validating the freedom of Kashmir, a land still occupied by the Indian state.

A need to understand ourselves at this entanglement of multiple positions brings our practices together. Continually guided by an insatiable desire for growth through inquiry, Silvi has often questioned what it means to decolonize Albania, and in extension their queer Albanian body, from all its layers of imposition—dictatorial, European, Ottoman, patriarchal, and beyond.

In a generous exchange while driving across the border between Albania and Kosovo, Silvi recounted their recent work at the perfocraZe International Artist Residency (pIAR), set up by artist-activist Va-Bene Elikem Fiatsi, just outside of Kumasi, Ghana. I attempt to share some of their reflections ahead here, while also thinking alongside them.

On arriving in this unfamiliar town, unfamiliar country, unfamiliar continent, Silvi found spontaneous resonance with the landscape, untarred, free of concrete. It evoked the memory of Mbrostar, Fier, their ancestral town in Southern Albania where they spent their early childhood. What a gift to hear the murmurs of earth unconfined by borders, visa controls, and even temporal regimes. What possibilities emerge in living in such a continuum of body and land?

In creating a process-based artwork through deep listening to the earth, their body—the artist sought to understand, “What does a power relation look like that is not from force, but comes from trust?” To cultivate trust and reciprocity, unlearning conditioning that reverts us to hierarchy, is a decolonial praxis. What role does deep listening play in this? The imprinted impulse for competition has taught us to listen only to be able to respond. Instead, what if we listen to feel co-presence, to begin to understand, to open possibility to be moved, might we build the conditions for shared respect, for the whispers of mutuality?

Silvi sat to listen to the earth with their hands. From within laborious processes of picking out stones, crushing clumps, and kneading the clay, the earth sang her song. Those passing through the market street where the studio was housed stopped by to ask if it was spice the artist was crushing, “Try it this way”, or “The women in my village use this technique when processing spices, let me show you”; the earth harmonised.

In the incessantly repeated gestures, notes were transmuted to the artist’s body; a call to listen to the pulses of pain that have long resided in fingers, wrists, and back muscles, asking to be acknowledged, to be seen with tenderness. The shackles of usefulness, the push for land to be profitable, the pressure to be a productive body have tied down colonised people for centuries, how do I undo their grasp on my mind?

In listening, to each other, to our selves and bodies, portals can open to move ‘slantwise’. Rooted verses manifested as seed-spheres of clay, made by and besides all those who stopped to offer a tune. The spheres and stones and stories from a nearby quarry where explosions screamed of capital’s greed formed themselves as a portal in the Silvi’s ear-mind-heart and studio.

Where do these portals, of listening and being seen, lead us to? What if it is not a location we move towards, but rather a way of locating ourselves in relation to the tangible and intangible entities that we live with? Entities that have long been denied vitality by enlightenment taxonomies. Autopoiesis—auto referring to the self, and poiesis as the act of bringing something into being—is the process by which in our myths we create ourselves anew, vision rejuvenated bodies, conjure ceremonies to resuscitate wounded archives.

Thinking outside the restraint of formal definition, of curtain and start and end, I see Silvi’s manifestation as a profound form of narration. In a collaborative process with the earth—shifting from a relation of force toward one of trust—the artist returns all 333 unfired red-clay spheres to the river stream along the path between their residency and studio, a gesture that serves as a parable for breaking the Cartesian divide. Body-earth tells their story through earth-body tells our story through body-earth. We move a tiny bit closer. Your story is not my story, but as it ripples through my heart, I hear the footsteps of my ancestors reverberate through the ground on which you stand.

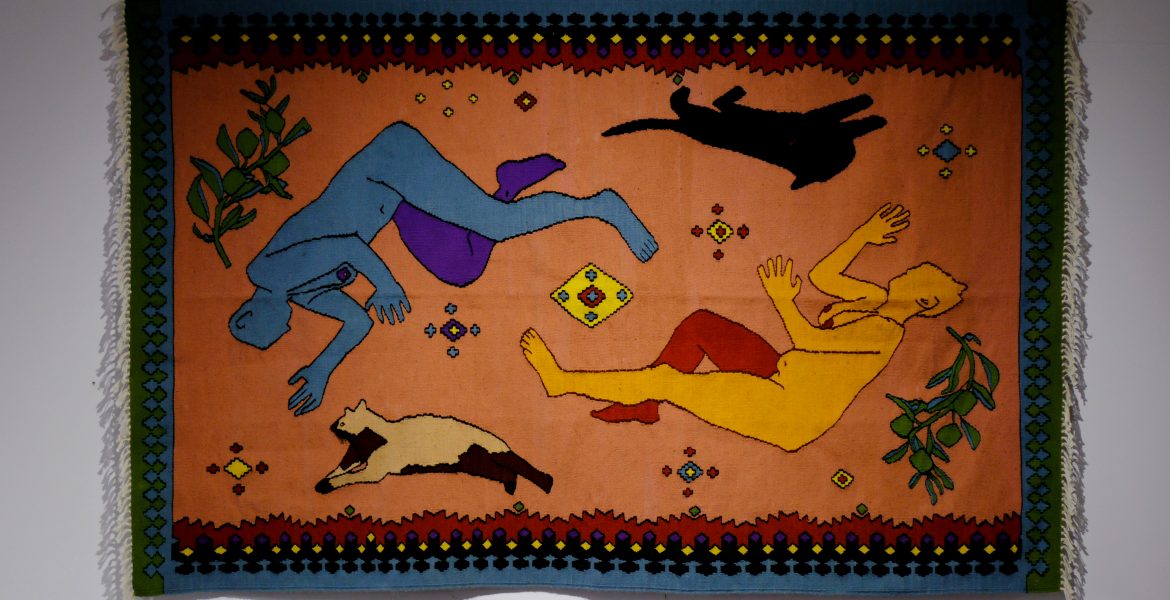

Feature image: Silvi Naçi with Dëshira Maja, Pa Titull (duke nxjerrë në hartë lirinë, me ullinj) / Untitled (mapping freedom, with olives), textile (wool, natural dyes), hand‑crafted in Krujë, Albania, 2024. Displayed at Wrapped in the Shadow of Freedom, Prishtina, 2024. Photo: Zana Begolli. Courtesy of Sekhmet Institute.

Shaunak Mahbubani (they/she) is a curator-writer based between Berlin and India. Their work focuses on practices that foreground personal and ancestral lived experiences, towards the resuscitation of wounded archives. From 2017-23, they curated the multicity project ‘Allies for the Uncertain Futures’ featuring over 100 artistic contributions across 7 international locations. Other notable projects include Wrapped in the Shadow of Freedom (Sekhmet Institute, Prishtina, 2024), Disrupting Protected Ignorance (Curated by Sajan Mani, with Shaunak Mahbubani, HKW Berlin, 2024), Dis-Visible Narratives (SAVVY Contemporary, 2024), and The Albanian Conference (initiated by Anna Ehrentein) at the 4th Lagos Biennial (2024). Their art writing has appeared in Artforum, Hyperallergic, NO NIIN, ArtIndia, Critical Collective and other platforms. See their work at www.shaunak.co