The city is one of humanity’s greatest inventions. Not because it is dense, or efficient, or economically productive, but because it made collective life possible beyond mere survival. The city separated humans from constant exposure to hunger, animals, and weather; it organized water, shelter, infrastructure, and care. But more than that, it organized culture. It allowed encounters, disagreements, and solidarities. It produced a critique.

It is in cities that emancipatory struggles historically took shape. Workers organized, women claimed public presence, communists, anarchists, and queers found each other and invented new languages of life. The city was never innocent, but it was fertile. It generated friction, and from friction, change.

Today, this achievement is under existential threat. Skopje itself was once conceived as a project against destiny. After the earthquake, the city was not only rebuilt; it was imagined. Reconstruction was an act of collective defiance against catastrophe, a refusal to accept disaster as fate. The post-earthquake city emerged as a future-oriented gesture, inscribed with utopian expectations of solidarity, social infrastructure, openness, and shared life. It was a city projected forward, not backward, a city that believed in planning as a form of care and in urban space as a condition for equality.

Yet from its very inception, Skopje existed in a permanent tension between history and utopia, between what had been lost and what was hoped for. That tension was not a weakness; it was its productive force. The city lived in the unstable present, where futures were imagined through the ruins of the past. Today, however, this tension has collapsed. Utopia has been privatized, reduced to individual escape or consumer fantasy, while history has hardened into destiny, unmanaged, unchallenged, repeated as inevitability.

The crisis of the present is precisely this: a city unable to project itself forward, trapped in an eternal now where destruction appears natural and alternatives unimaginable. As Giulio Carlo Argan reminds us, the present is never stable, it is only a future flowing into the past. When a city loses the capacity to imagine itself otherwise, it does not remain neutral; it begins to decay.

What we are witnessing in Skopje is not only environmental collapse, but the exhaustion of the city as a project, the substitution of collective future with administered fate. The question is no longer how to preserve an inherited city, but how to reopen the space where utopia and history can again confront each other, because without that confrontation, the present becomes an endless crisis with no exit.

In Skopje, the crisis announces itself most brutally through the air. Breathing has become a daily risk. The city no longer begins at the street, but in the lungs. And this is not an accident of geography or climate. It is the material outcome of political decisions, tolerated crimes, and an urban model that treats the city as a disposable surface for profit extraction.

Factories burn waste because it is cheaper than responsibility. Construction advances because regulations have been hollowed out by corruption. Trees disappear, sidewalks shrink, public land is enclosed. Everything is justified in the language of “development,” while life becomes increasingly unlivable. Pollution is not a side effect, it is the signature of governance aligned with capital, not with inhabitants.

Yet this catastrophe cannot be explained only by corrupt politicians or predatory investors. It also has a social dimension. Over decades of neoliberal pressure, citizens were trained to retreat. Survival became individual. Care became private. The public space was gradually abandoned, perceived as dangerous, useless, or irrelevant. The city was reduced to a corridor between home and work.

Public space must be transformed into common space. As long as it is treated merely as a resource for circulation, from home to work, from work to school, from school to shopping mall and back home again, the city remains a machine of avoidance. Streets become corridors of impatience, squares dissolve into crossings, and urban life is reduced to movement without encounter. This logic produces dispersion in the form of isolated bodies, parallel lives, accumulated exhaustion. The psychological pressures generated under these conditions, those of loneliness, frustration, insecurity, are not private pathologies, but socially produced effects of late hyper-market capitalism, structured through space itself. When spaces of commonness are denied, these pressures return to the public realm in distorted forms. As impatience, selfishness, aggression, and ultimately violence.

The city begins to feel hostile not because people are inherently hostile, but because they are deprived of the conditions for shared existence. Responsibility here cannot be grounded in innocence. We live inside the very city we criticize, implicated in its infrastructures, rhythms, and compromises. But implication does not absolve responsibility, it rather defines it. Responsibility today does not mean moral superiority or purity, but acting from within damaged conditions, without guarantees and without waiting for permission. Self-organization, in this sense, is not a choice made by the virtuous, but a necessity imposed on those who wish to continue living together. There is, therefore, a fundamental choice at the heart of urban life: either the commoning of space, or barbarism. This choice is nothing other than the reopening of the city as a project, against its reduction to destiny.

Public space never remains empty. When citizens withdraw, other forces occupy it. Today, streets and squares are increasingly used for nationalist masquerades, spectacles of identity, tradition, and authority that offer belonging without responsibility. Young people, deprived of future-oriented narratives and collective horizons, are drawn into simplified ideologies that promise order, pride, and hierarchy. The city is imagined not as a shared commons, but as a territory to be symbolically purified and ideologically disciplined.

In this process, the real problems disappear from view. Air, water, housing, mobility, care, the commons that make life possible, are eclipsed by flags, rituals, and staged conflicts. Nationalism thrives precisely where social infrastructure collapses. It fills the void left by the destruction of collective life, while doing nothing to stop the destruction itself.

At the same time, urban capital advances without resistance. Construction mafias reshape entire neighborhoods. Density increases without care. Profit-driven urbanization consumes space, light, air, and time. The city becomes a machine that generates its own demand: politicians authorize, businesses extract, institutions legitimize. This is not mismanagement, it is a coherent system of devastation.

Skopje is not an exception. It is following a trajectory already visible across the Balkans, where cities are slowly transformed into chemically toxic and politically hostile environments. Places where progressive cultures once emerged are turning into graveyards for dissent, experimentation, and solidarity. Urban capital has no interest in culture, history, or future, only in turnover.

The question, then, is not whether politicians will solve this crisis. Thirty years of devastation have already answered that. Why should we believe that the interests which produced this situation will suddenly reverse themselves?

There is no salvation coming from above. What is required is a different form of struggle, one that does not rely on grand narratives or abstract promises, but on localized, concrete, self-organized practices. The city will not be reclaimed through representation alone, but through presence.

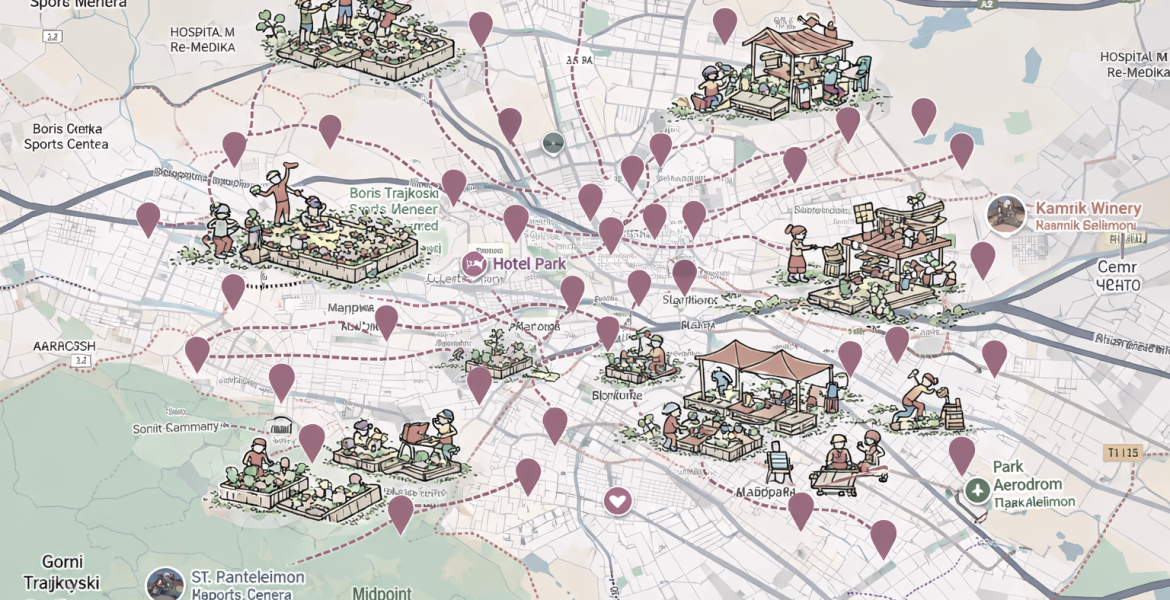

Urban gardens, car-free zones, community kitchens, neighborhood assemblies, cultural centers, shelters, collective care initiatives, autonomous festivals, these are not lifestyle choices. They are political acts. Forms of urban self-defense. They reassert that the city is not a commodity, but a condition of life.

We are far more numerous than politicians, police forces, or administrative structures. Power depends on passivity. A city with dozens of self-organized initiatives cannot be easily controlled, disciplined, or ignored. Self-organization multiplies capacities, creates resilience, and interrupts the smooth functioning of extractive systems.

This may sound utopian in the Balkan context. But the real illusion is believing that the current path is sustainable. Without direct intervention from citizens, Skopje will become increasingly uninhabitable, a place people escape from, not live in. Toxic both chemically and politically. Deserted not only physically, but culturally.

And beyond the superficial idyll of non-urban alternatives, it is still cities that generate movements, solidarities, and historical ruptures. Abandoning the city means abandoning the possibility of collective change.

From streets to skies, everything is connected. The way we build, tolerate, withdraw, or resist accumulates in the air we breathe. The city is already responding to decades of neglect. The only remaining question is whether citizens will respond in return, not as spectators, not as voters alone, but as active producers of urban life.

There is no other ally left. Only the self-organized citizen, acting directly to fulfill the most urgent needs of collective existence, can still prevent the city from collapsing into a space of managed suffocation. From streets to skies, this is no longer a metaphor. It is the terrain of struggle.

Artan Sadiku