Since 2011, the European Union has been facilitating a dialogue between Prishtina and Belgrade with the goal, in the EU’s own words, of “achieving a comprehensive legally binding normalization agreement” between the two capitals. Such an agreement would have tremendous positive implications for the international standing of both countries, their economies, and their citizens. It would also signal that Serbia and Kosovo are ready to come to a shared understanding of their past and jointly project into the future.

While today such a resolution appears as elusive as it did over a decade ago, a number of partial agreements have been reached along the way. However, many of these remain dead letters, and with Prishtina and Belgrade exchanging recriminations as harsh as those from 14 years ago, confidence that the dialogue can eventually yield its longed-for results is waning.

As part of initiatives aimed at opening up reflection on the dialogue, forumZFD has interviewed Serbian politician Nenad Čanak. This interview was conducted as part of a study by Professor Bardhok Bashota of the University of Prishtina on the perceptions of political and social elites in Belgrade and Prishtina regarding the EU’s role in this process.

Čanak, co-founder and former leader of the center-left League of Social Democrats of Vojvodina (LSV), served as President of the Assembly of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina between 2000 and 2004 and was a member of the National Assembly of Serbia until 2020. Known for his staunch support for decentralization and antiwar activism, we spoke with Čanak in May 2024 to discuss his perspective on the EU’s role in the dialogue. Perhaps reflecting the stagnation of the dialogue itself, his views appear equally relevant today.

forumZFD: What do you think of the EU’s role as a facilitator in the Kosovo-Serbia dialogue? Does it seem to you partial or impartial?

Nenad Čanak: The dialogue between Belgrade and Prishtina is one of the trickiest issues in world diplomacy as multiple truths are involved, and depending on one’s standpoint, certain truths may seem more valid than others.

Not only, the EU itself is not a homogeneous structure. EU member states hold conflicting views — Spain, for instance, refuses to recognize Kosovo’s independence due to its own issues with Catalonia, while Germany believes lasting peace requires federalization or the dissolution of states into sustainable entities. As a peace project born from World War II, the EU’s inefficiency is understandable — it must build consensus among diametrically opposed perspectives.

Personally, I fully support Kosovo’s independence and believe that the only path forward is to normalize relations diplomatically between Serbia and Kosovo. Serbia should not impose additional demands or attempt to influence Kosovo’s international status. Kosovo became part of Serbia through war, and it gained independence through war — there is nothing extraordinary about this.

Yet, on the other side of the table, a legalistic approach is being used and abused in Serbia. In Belgrade, the issue of Kosovo is persistently framed through the lens of UNSCR 1244 or other international documents and UN charters. But these are just excuses. You cannot squeeze real life into a sheet of paper. You cannot force real life into a Procrustean bed and cut away what doesn’t fit your opinions.

The Kosovo issue is exploited for domestic gain not only in Belgrade’s official diplomacy but also among most Serbian political parties. As a result, only a small portion of the Serbian population agrees with me that Kosovo is and should be independent. Since Milošević’s era, every regime has used the Kosovo issue to create a smokescreen that obscures their abuses of power.

The EU is vulnerable to Serbia’s legalistic tactics, with some EU parliaments echoing these arguments for their own domestic agendas. Given the EU’s very nature, efficiency in this process cannot be expected. This step-by-step strategy has not yielded real, lasting results and is proving too slow for everyone.

Do you see any change on the horizon?

Surprisingly, the Banjska terror attack seems to have accelerated the process by stripping away the facades of both Belgrade and Prishtina politics. Belgrade needs something to mask its weakness — essentially, to obscure the reality that Kosovo is an independent state. Orchestrating problems in North Kosovo is enough to create the impression within Serbia that Serbia is fighting a righteous war for Serbian people everywhere, starting with Kosovo. And that, in a nutshell, is why people in Serbia should not question their own living standards, European integration, and other important issues.

The EU isn’t helping much, although there appears to be more movement after Banjska. Yet, no one is asking the real questions. We need to ask: Are we waiting for all the Serbs in the north of Kosovo to flee or die out? Young people don’t want to stay there; they don’t see a future because they aren’t integrated into Kosovo society.

Serbia needs tensions in the north of Kosovo. It needs the Serbs there not to integrate into Kosovo society. It needs them as a permanent source of tension. Through these tensions, the government can keep Serbian society in a permanent state of post-traumatic stress and war psychosis. This is essentially what’s happening: instead of promoting integration, the Serbian government has asked Kosovo Serbs to leave Kosovo institutions and harasses those who participate in them.

The EU isn’t addressing the real issues or pushing the right buttons. When it came to Ukraine, they understood the situation, recognized Russia as the aggressor, and imposed direct sanctions. If Russia’s intelligence network in Serbia is too strong to allow similar measures, we can offer assistance to expel Russia’s spies and agents.

Unfortunately, the EU is currently led by bureaucrats rather than statesmen who grasp the broader context. Whether it’s Kosovo, Bosnia, or the Middle East, all these issues trace back to the Kremlin, which is using these interconnected conflicts to divert international attention from its aggressive policies toward neighbors like Georgia and Ukraine. Without recognizing this, the EU’s response will remain inadequate.

So what is the role of the EU?

The EU is currently at a critical juncture. I think and hope it will prevail, but to do so, it must define its role in Europe once and for all. With its significant economic strength, the EU cannot afford to have a lackluster and inefficient foreign policy. It needs to develop European armed forces and a clear strategy for common defense, rather than relying only on NATO. If the US steps back, if Trump wins again, Europe will be easy prey for the Kremlin. Understanding our local issues requires understanding the broader context.

It’s been over ten years since the EU began facilitating the Prishtina-Belgrade dialogue, with many agreements signed. Do you think the EU has maintained a clear position on the dialogue’s agenda? Has it proven to be a reliable and credible mediator?

In politics, results speak for themselves. Is something good or bad? Simply ask if it’s working. The EU’s approach to the dialogue isn’t yielding sufficient results because it hasn’t set clear terms or enforced consequences for non-compliance. I see EU officials adopting an arrogant attitude towards Serbia and Kosovo, treating us like primitive tribes they need to civilize by imparting wisdom and political arguments.

I experienced this firsthand during meetings at the European Parliament on Western Balkan integration. EU representatives would make speeches and then leave for more important matters, leaving us out of the conversation. I recall an Albanian colleague saying, “If you think we’re here just to listen to your wise words — using ‘wise’ sarcastically — we won’t come anymore because it’s utterly humiliating.”

The issue goes beyond disrespect — it’s about accountability. If someone doesn’t honor their commitments, they should face consequences, but the EU hasn’t enforced this in the dialogue. Meanwhile, the EU’s soft power pales in comparison to Russia’s persistent efforts. Moscow is constantly, even as we speak, expanding its influence, buying politicians, and destabilizing countries, starting with Hungary, yet the EU isn’t reacting. You can’t claim to resolve the Prishtina-Belgrade issue while failing to support the people of Georgia, who are fighting not to be under the Russian boot. These issues cannot be treated as separate because the world itself is not separate.

Do you think the EU has been enabling Serbia’s political goals in the dialogue?

The EU is behaving like a bad teacher. When a problematic student disrupts the class, the bad teacher gives them more attention, hoping to manage their behavior, while neglecting the well-behaved student, assuming their job is done. Similarly, the EU views Prishtina as inherently pro-European, pro-American, and pro-Western, while in Belgrade, they must counter the toxic influence of Russia and China. In my opinion, this approach is completely wrong, leading to the slow progress we’ve seen.

There are various processes affecting Kosovo-Serbia relations, like the Berlin Process, Open Balkans, and France’s stance on the dialogue. Do these initiatives align with or conflict with the EU’s strategy?

The fact that there are multiple strategies indicates a lack of coherence, which essentially means there’s no strategy at all. You can’t keep introducing new initiatives and expect them to work; it’s like adding more dice to a game without changing the rules. Without a clear and unified European policy, nothing significant will happen. Unfortunately, EU bureaucrats lack vision — they’re just trying to survive, not to lead. The rise of right-wing organizations and troubling alliances between North Korea, China, and Russia are creating serious challenges for the EU’s leadership.

Do you think the EU has been swayed by Serbia to change its approach and agenda for the dialogue, or is it rather ignoring the demands and internal dynamics on the Serbian side?

There’s a saying: “You cannot wake someone who is pretending to be asleep.” This is the strategy of the Serbian regime. They claim issues like the land of the monastery of Dečani are red lines that must be resolved before negotiations can continue. Yet, when that land was returned, Serbian media ignored it because it was no longer politically useful.

Vučić’s tactic is not new; previous regimes, including Milošević’s, used it effectively against the EU. In the 90s, Belgrade’s slogan was “The first line of defense of Belgrade is Knin,” referring to the so-called Republic of Serbian Krajina. Once defeated, this slogan and the plight of those who fled were forgotten.

We often see Vučić with Dodik, the President of Republika Srpska in Bosnia and Herzegovina. However, we don’t see representatives of Serbs in Croatia. Why? Because they are integrated into Croatian society. This is something the EU struggles to understand: this is the path we need to follow.

When we treat Serbs as a monolithic group, like a single entity that remains the same regardless of context, we encounter problems. My friend Veton Surroi once pointed out that Albanians value the polycentric development of their nation — a historic achievement in civilized nation-building that contrasts sharply with the Serbian idea of uniting all Serbs in one state. The key to normalization is to demonstrate to Serbs in Kosovo, Montenegro, and Bosnia that these are their respective states.

If Serbia’s loss of 18% of its territory due to Kosovo’s secession troubles anyone, remember that Serbia lost the war — a war that began with the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Albanians from Kosovo. This situation is not unlike post-World War I Hungary, which saw two-thirds of its territory and half its population, mostly ethnic Hungarians, vanish overnight. Losing a war comes with consequences, and losing territory is part of that price.

Unfortunately, the EU’s ‘No one should be a loser’ policy means systemic policies behind these horrors are never condemned. While some individuals have been tried, the genocide in Bosnia and the atrocities in Kosovo were not the work of a few individuals alone; they were driven by a system based on a specific ideology. Unlike Nazism in Germany and Fascism in Italy, this ideology has never faced trial.

You’ve repeatedly mentioned the importance of understanding the broader picture. When it comes to Serbia’s global stance, its position is quite ambiguous — supporting Russia while also wanting to become an EU member…

… and at the same time, supporting Ukraine with ammunition.

Exactly. Do you think the EU has been able to convince Serbia that joining the EU is the only path forward, and that to follow this path, Serbia must align itself with the EU both in the dialogue and beyond?

The EU is ineffective because it is not pressing the right buttons. You use the word ‘convince,’ but it is impossible to persuade someone to act against their own interests. The Serbian elite’s interest lies in maintaining a state with minimal rules, where high-ranking members of the ruling party can act with impunity.

Take Radoičić, who is believed to have organized the terrorist attack in Banjska and is currently in Serbia. He should be immediately expelled to Kosovo. The EU should clearly state: a terrorist attack occurred, and we have zero tolerance for terrorism. Terrorists must be extradited to the countries where they committed their crimes. What’s so complicated? Has anyone in the EU ever stated this or threatened to treat Serbia as a terrorist haven if it fails to comply? Not once.

Why? No one wants to stir up trouble, especially when the Serbian opposition might act similarly if it gains power. We’re seeing the American philosophy in action: ‘If you want to do business in hell, you have to deal with the devil.’ This was true in the 90s and remains true today. They negotiate with Vučić because he’s the one available and will give them what they want under pressure. If the opposition comes to power, there’s uncertainty about who they’d negotiate with and how influenced they’d be by Russia. The EU’s soft approach in a hardball game isn’t working.

When discussing the EU playing hardball, I think of the sanctions imposed on Kosovo for actions like installing Kosovo/Albanian mayors and police operations in the north, which the EU viewed as escalating tensions leading up to the Banjska attack. What do you think of these measures?

I don’t understand the issue with installing Albanian mayors when Serbs didn’t participate in the elections. Don’t those who voted have the right to representation?

True, this was a major public debate, but the reaction was strong, even violent, when the elected officials tried to approach municipal buildings.

And whose reaction was that?

That’s for you to answer.

No, it’s a question for those trying to privatize the state. Their stance is: without us, there’s no state, no peace. That’s unsustainable for any country. When Albanians boycotted elections in Milošević’s Serbia, it kept him in power for at least eight more years. Had they participated, there might not have been a Milošević in the early 90s, and the endless bloodshed that followed could have been prevented.

We see the same thing here. No one is thinking about what’s good for Kosovo or Serbia — it’s all about private interests. They claim they can’t live under Kurti’s ‘terror,’ yet Serb police officers resign and say, “Now we have no protection.” This is pure obstruction. I don’t believe this is what caused the Banjska terror attack — it was just an excuse. I saw this exact scenario play out 34 years ago in Croatia.

It’s simple: you send trained professionals to incite conflict, set up barricades, and keep them in place for 24 hours. Meanwhile, you spread rumors, “They’re coming to kill us, we must defend our homes,” and arm civilians, pushing them to the barricades. Civilians die, and then international forces step in to create a buffer. In reality, these forces are protecting the borders of a newly formed territorial unit, similar to what happened 34 years ago with the creation of the Serb Autonomous Regions (SAO) in Croatia.

Now, the current version is to create a new Serbian entity in Kosovo — perhaps calling it Serbian Municipalities, leading to a permanent crisis like in Cyprus. Vučić and his government now have to step back because they can’t repeat this scenario — it’s too obvious. Ironically, those organizing this were likely encouraged by those wanting it to fail, as a way to weaken them with accusations of harboring terrorists.

The situation runs much deeper than it seems. The EU is acting very naively. If they wish to mediate in the Balkans, they need to first understand where they are and who they’re dealing with.

Returning to the issue of legitimacy, the EU and QUINT countries argued that the 2023 local elections in the north lacked full legitimacy due to low participation from the Serbian community. They advocated for a repeat election, but once again, when a new vote was held to dismiss the ethnic Albanian mayors in 2024, participation from the Serbian community remained low. Do you believe the Albanian mayors are now more legitimate?

If people in North Kosovo want to change their local government, it’s simple: start a civic initiative and collect signatures to request new elections. If you want to be part of a society, follow its rules. If not, you can’t expect that society to treat you like its own citizens.

I also dislike the phrase ‘the Serbs in the north of Kosovo’ — they don’t all think the same. For instance, car plates were a major issue; people switching to Kosovo plates used to have their cars burned. Now, they’re changing plates without any trouble — I’ve even seen them in Novi Sad, no problem. So, what was the issue a year ago that no longer exists today?

If they truly want change, they can call for new elections. It seems, though, that they’d rather have the international community beg them to have elections in the place where they live. When parts of the electorate in Serbia boycotted the 2012 elections, it led to Tomislav Nikolić, former deputy to indicted war criminal Vojislav Šešelj, becoming president. The point is, if you leave emotions aside and stop trying to be overly politically correct, the path forward is clear.

Looking ahead, do you think the EU can still drive Prishtina and Belgrade toward a binding agreement that ensures democratization and progress toward EU membership?

The idea that the Belgrade-Prishtina dialogue binds the fates of both countries is flawed. Kosovo is pro-Western, meets EU standards, yet its progress depends on Belgrade’s approval, which is unfair to Kosovo. Similarly, if Belgrade changes its policies, why should it be held hostage to unacceptable demands from Prishtina? After all these years, it’s clear that the real beneficiaries of this chaos are the so-called Serbian patriots in Kosovo, while the Serbian community there continues to shrink.

Assuming the EU espouses your views, what actions should it take? What should its position be?

The EU should focus on three simple questions: What has been agreed upon? When must it be implemented? And what happens if it isn’t? It’s so straightforward, and perhaps that’s the problem.

Take Ukraine, for example. For the longest time, the strategy was to avoid provoking Moscow. Yet for over two years, Russia has relentlessly destroyed Ukraine. I visited Kharkiv shortly after the Russians were pushed out of the city outskirts. The devastation was horrific — cluster bombs and every type of ammunition had been used against Ukrainians. A year later, protests erupted at the United Nations about Ukraine’s possession of cluster munitions, even though Russia had used them much earlier.

All these narratives and strategies are just tactics to buy time, and buying time is the worst thing the European Union could do. It’s no longer a time for negotiations. As we speak, Serbia is preparing for the UN resolution on the Srebrenica genocide, which they claim will “hurt the hearts of the Serbian nation and people.” Two days after the resolution, there will be a major meeting to discuss the creation of a united Serbian state. This is just an excuse. No one is claiming Serbs as a nation are genocidal – there’s no such thing as a genocidal nation. Serbian nationalists and centrists, however, use this narrative to create a sense of victimhood and push Russian-style propaganda. But the real focus should be on what was agreed, when it should be done, and the consequences if it isn’t.

As we wrap up our discussion, is there anything we haven’t covered that you’d like to add?

To solve the Western Balkans issue, focus on the regions no one talks about, like the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina. It’s multi-ethnic and multi-confessional, with excellent inter-ethnic relations, despite being taken over by Slobodan Milošević in 1988 and having its ethnic and political makeup forcibly altered to this day. For a solution, consult people from areas where coexistence works, like Southern Tyrol, where Germans and Italians live side by side, or Vojvodina and Istria, where communities thrive together. Don’t ask politicians from Herzegovina, Belgrade, or Zagreb — they don’t know how to live together.

This article has been edited for length and clarity. The interview was conducted in English.

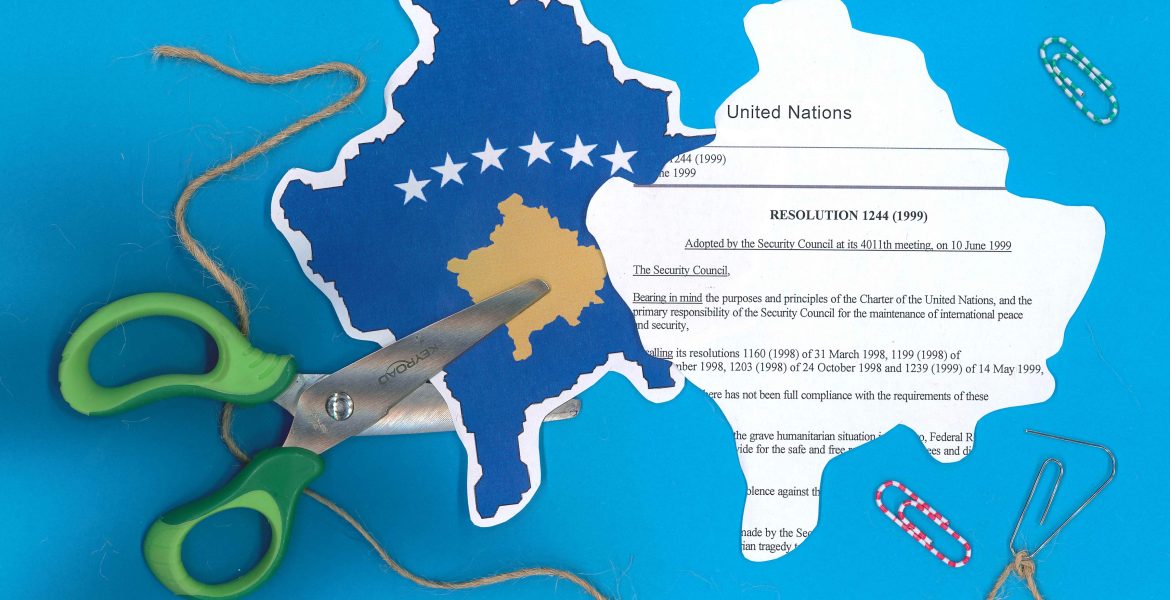

Feature image: Luca Tesei Li Bassi/forumZFD