In 2020, Pro Peace in Kosovo and Oral History Kosovo launched a project to document and archive the lived experiences of miners and others involved in the 1989 strikes at the Trepça mines — a large industrial complex in northern Kosovo that held significant economic importance under Yugoslavia and has remained highly symbolic in Kosovo ever since. The strikes began in February 1989, when Trepça miners initiated a hunger strike to protest the Socialist Republic of Serbia’s abolition of Kosovo’s autonomy. Many consider this event a key turning point — if not the starting point — in the dissolution of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

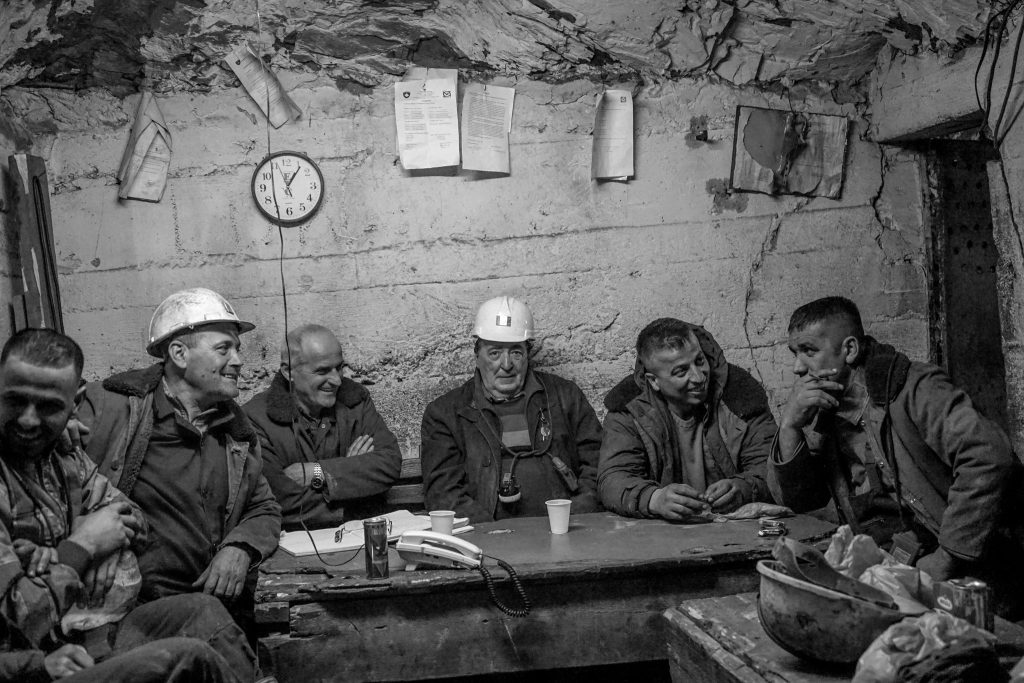

After conducting desk research and analyzing archival materials from Kosovo’s National Library, Kosovo’s State Archive and the archive of Radio Television of Kosovo, we began cooperating with the Independent Union of Trepça Miners. Gani Osmani, a Trepça miner and participant in the 1989 strike, as well as the acting head of the union, readily agreed to support our research.

This support proved instrumental, as we realized the need to gather oral history testimonies from the miners themselves, documenting the 1989 strike beyond the limitations of traditional archival resources. Osmani was one of the first miners we interviewed, opening the door to the discovery of a mosaic of interconnected experiences and human perspectives often missing from official narratives.

In the weeks that followed, we conducted 24 more interviews, which we then organized to highlight fundamental threads in this recounting of the miners’ (hi)stories while providing a deeper, multilayered understanding of life, politics, economy and culture in Kosovo at that historical moment. Using oral history techniques, we gathered their accounts, recorded them as audiovisual materials, and transcribed them faithfully, without editorial intervention.

The interviews uncovered the intricate dynamics of the strike — its underlying motivations, the organizational efforts behind the mobilization, the hardships and violence miners endured, as well as their ideals, resilience, resistance and sacrifice. They also shed light on the lasting political impact of the miners’ activism. From these conversations, a living archive of collective memory emerged. The significance of this archive lies not only in its ability to provide new, reliable historical sources and accounts but, more importantly, in serving as a platform for voices that too often remain on the margins of written history.

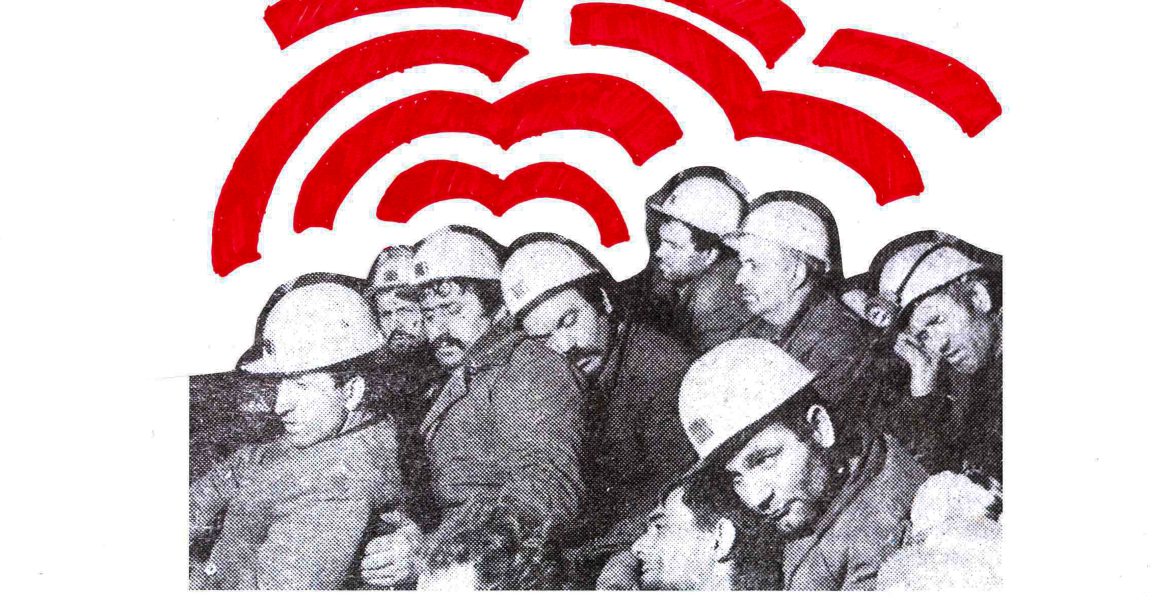

This research informed the exhibition A Site of Political Struggle: Trepça Mine 1989, curated by Erëmirë Krasniqi and installed at the National Museum of Kosovo throughout February 2023, exactly 34 years after the strike. The exhibition welcomed miners, students, school groups, decision-makers and tourists in what Krasniqi described as a choral work reflecting “the commitment to understanding new forms of political engagement that emerged during the miners’ strike.”

From its inception, our deep dive into the memories of the Trepça strikers aimed to create a corpus of research that would remain dynamic and evolving. In this spirit, in the years that followed, sociologist and Oral History Kosovo co-founder Anna Di Lellio further developed the materials, structuring these oral histories to integrate them into a broader political and historical framework — ensuring their radical relevance is fully recognized.

In 2024, Di Lellio published the book La Jugoslavia crollò in miniera – Kosovo 1989: Lo sciopero di Trepça e la lotta per l’indipendenza (Yugoslavia collapsed in the mine – Kosovo 1989: The Trepça strike and the struggle for independence). A year later, Pro Peace and Oral History Kosovo published the book in Albanian (under the title Jugosllavia u Shemb në Trepcë), translated by Majlinda Bregasi and edited by Aulonë Kadriu.

Whether examined through the lens of pedagogy or the politics of memory, the discourse on the 1989 events in Stan Tërg (the town hosting the Trepça mines) remains crucial. Too often, Kosovo’s past is exploited and monopolized, with its traumas swinging like a pendulum between glorification and victimization — both reductive and one-sided — depending on the shifting political dynamics of the moment. In this climate, the civilians’ experiences of resistance are overlooked, with their contributions to sociopolitical change stripped from the writing of official history.

Why did Yugoslavia fall in the Trepça mines?

The 1990s marked the dissolution of Yugoslavia, transforming it from a unified socialist state into a group of independent republics embroiled in ethnic and political conflicts — and ultimately, war. By the late 1980s, the rise of nationalism, coupled with a deepening political crisis, had destabilized Yugoslavia. In 1989, Slobodan Milošević became the leader of the Socialist Republic of Serbia, emerging as one of the era’s most polarizing figures. He tightened control over federal institutions and amended the Serbian constitution to revoke the autonomy of Kosovo and Vojvodina. These actions triggered strong reactions in Kosovo and further heightened tensions among the federative republics.

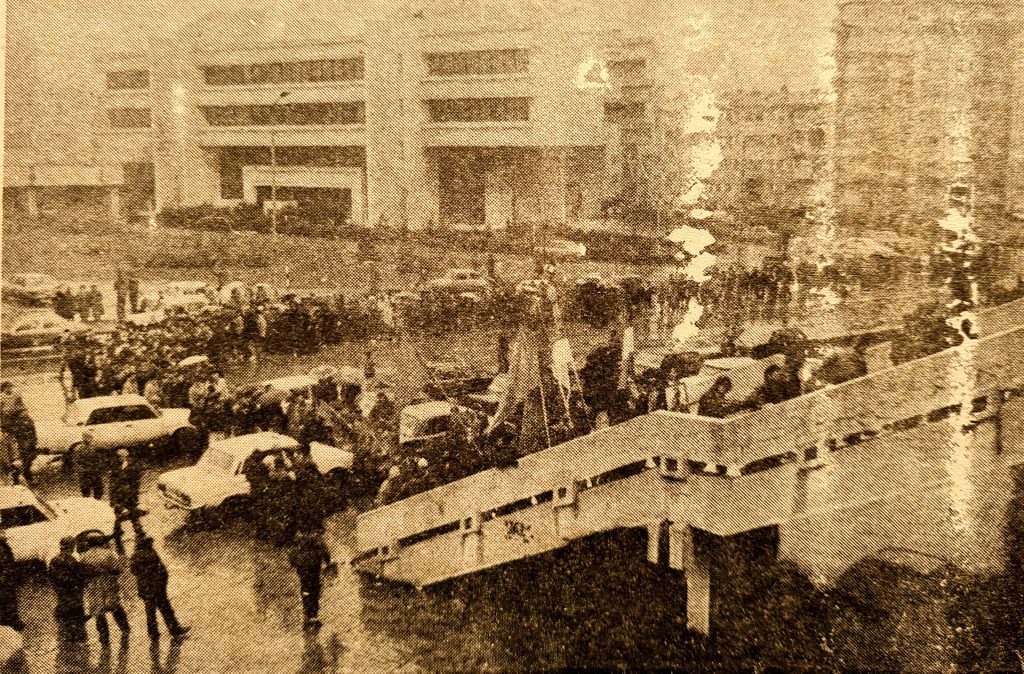

On November 17, 1988, workers and miners from the Trepça mining complex marched to Prishtina in protest against constitutional changes aimed at revoking Kosovo’s autonomy. Faced with systematic prosecution following the march, the miners launched a strike on February 20, 1989. This strike became one of the most powerful acts of resistance by the working class against the oppression of Kosovo Albanians and the systemic inequalities they faced in Yugoslavia.

On Monday, February 20, 1,350 miners launched a strike 600 to 800 meters underground at the Stan Tërg mine. Their demands were exquisitely political: to protect Kosovo’s autonomy, demand the resignation of leaders imposed by Belgrade, end discriminatory policies against Albanians, and internationalize the Kosovo issue. As philosopher Shkëlzen Maliqi noted in an article published on the final day of the 1989 strike, this marked a difficult yet cathartic moment for Kosovo Albanians, unleashing years of suppressed outrage.

The resistance of Trepça’s working class inflicted significant economic damage on Yugoslavia, but its impact reached far beyond that. The miners’ struggle sent shockwaves through the Yugoslav political system and was met with harsh repression, including arrests, mass layoffs, and further deterioration of Kosovo’s political climate. Yet the miners’ determination strengthened a collective identity — not only among the strikers but also within society at large — turning it into a symbol of resistance, solidarity and justice. This collective spirit fueled movements such as the campaign for blood feud reconciliation and union organizing under the principle “a family helps another family.”

The book Jugosllavia u shemb në Trepçë by Anna Di Lellio provides a thorough account of these events. Drawing on the life stories of miners and other key individuals, alongside in-depth historical and political analysis, it sheds light on the complexities of the strike and its broader impact. Through interviews and selected documents, the book reveals how the miners’ physical endurance and political aspirations converged during a pivotal moment that shook the foundations of Yugoslavia.

Seen from this perspective, the Trepça miners’ strike was not only a direct confrontation with oppressive power and discriminatory policies but also a site of political struggle — an assertion of human dignity and an act of defiance that ultimately altered the course of history.

This book is more than a recollection of past events — it is a reflection on how workers’ resistance and social movements shape history and the many stories within it. Beyond documenting what happened, it offers deeper insight into the role of workers in the political history of Kosovo, the region and beyond. The events it recounts reveal a (hi)story that must be told and a truth that must not be forgotten.

This article is an edited version of Korab Krasniqi’s preface to the book “Jugosllavia u shemb në Trepçë.”

Feature image: Luca Tesei Li Bassi/Pro Peace, featuring photography from the newspaper “Rilindja.”