The European Union’s green transition has opened a new chapter in the relationship between Europe and its peripheries, both within and beyond EU borders, most recently through the EU’s Green Deal which aims for net zero emissions by 2050.[1] Although Bosnia and Herzegovina has formally adopted EU climate regulations and strategies, limited institutional capacity and financial constraints have ensured that the transition manifests as extractive exploitation rather than environmental protection, effectively enabling the EU to externalize environmental costs to its periphery. Meanwhile, grassroots environmental movements that challenge extractive logics and divisive frameworks imposed through the Dayton framework have emerged. Many transcend ethnic divisions institutionalized by postwar peacebuilding and are offering a model for decolonial approaches to peace. By centering the voices and strategies of actors and communities defending their land, water, and other natural resources, we can identify practices that point toward decolonial peace work in a post-war setting such as Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Natural Resources, Critical Raw Materials, and Peripheral Sacrifice(s)

The European Union’s Critical Raw Materials Act, which came into force last year, explicitly targets the Western Balkans as a source for minerals essential to Europe’s digital and green transitions. Bosnia-Herzegovina has become a particular focus, with an estimated 1.5 million tons of lithium carbonate, 94 million tons of magnesium sulfate, and 17 million tons of boron located just under the hills of Majevica. These minerals are not merely “critical” but “strategic” resources on the EU’s priority list, driving unprecedented corporate interest in Bosnian extraction sites (see Lippman’s writing on this here). The country’s rivers, streams, and lakes are plagued with pollution from mining, an onslaught of dams and small hydropower plants, and a lack of regulation in combination with corruption that fails to recognize its water as one of the most valuable resources.[2]

This regulatory double standard is not an accident but a structural feature. As Daniela Lai demonstrates in her analysis of Bosnia’s transition, the international intervention promoted “neoliberal restructuring” that “ultimately contributed to the subordination of social grievances to market logics,” relegating socioeconomic justice to the backbench rather than centering it as part of broader transitional justice concerns.[3] Bosnia’s weak state institutions, often lamented by international observers and scholars alike, ultimately serve the interests of extractive capital by creating conditions where environmental and social protections can be circumvented.

Horvat, arguing for the need for more environmental activism and green politics in the region, documents how the Balkans are portrayed as perennially lagging, stuck in a perpetual process of catching up, making extractive projects justifiable as development opportunities on the path to EU membership.[4] There’s an argument to be made that this has colonial logics behind it as EU based extraction of minerals is largely avoided while it is capitalized on in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Balkans more broadly. Thus, the metropole preserves its own environment while externalizing ecological destruction to peripheral territories, namely non-EU member states.

Widespread corruption, weak rule of law, and self-interested political elites in Bosnia and Herzegovina have created conditions that facilitate extraction.[5] Local political elites often defend these through arguments that they will bring about jobs, create development potential, lower energy costs, and further Europeanization processes. Elsewhere, Hodžić and Ćurak have examined how civil servants, aware of the limitations of the Dayton system, stuck between yugonostalgic notions of grandeur and visions of a European future, may consider the implementation of energy and environmental policies less critically.[6]

Yet as environmental activist networks document, these projects bring not only development but destruction: poisoned water sources, air pollution, resource exploitation, and the systematic elimination of sustainable livelihoods.[7] Environmental destruction is rendered invisible or acceptable because it occurs in spaces already constructed as peripheral, while local institutions and political elites are unwilling or unable to break free from corrupt networks and clientelistic relationships that facilitate environmental exploitation by both domestic and foreign actors. This only perpetuates Bosnia and Herzegovina’s semi-peripheral status within European socio-economic and political hierarchies.

Environmental Resistance as Decolonial Peace Practice

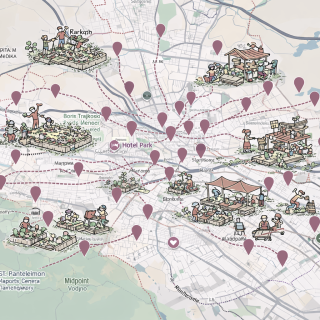

Environmental movements across Bosnia-Herzegovina have, over time, developed multiple repertoires of resistance that combine legal advocacy, direct action, and popular mobilization, especially through the media. They have gathered signatures and petitions to withdraw permits, organized mass demonstrations, public forums, debates with politicians, and collaborated with biologists and other scientists to document ecological destruction. These actions represent more than environmental advocacy – they constitute practices of democratic participation that challenge corporate power and governance models that enable extractive and harmful practices. Organizations like the Network for the Defense of Nature work with Citizens Association Fojničani, the Trstionica and Boriva organization[8], activists in Jajce, to name just a few, coordinate resistance strategies[9] and share resources. These networks operate according to principles of mutual aid and collective action, challenging the fragmented political landscape of Bosnia and Herzegovina today through their shared belief in the importance of preserving the environment. Such resistance demonstrates that development must be defined by communities themselves rather than imposed by external actors, just as peacebuilding.

Focusing on protests in 2014, Lai noted that “horizontal participation and rejection of ethnic characterizations” could emerge from socioeconomic struggles, offering “a key test for international agencies in dealing with social grievances that had been muted until then”.[10] As Lippman observes in his recent six-part series time and time again, environmental threats are bringing together people who have lived memories of fighting in the very same areas they are now working together to protect.[11] This cross-ethnic solidarity emerges not through internationally mandated reconciliation programs, but through shared material conditions and a realization that environmental catastrophes affect communities across ethnic lines throughout the country.

Environmental destruction transcends the artificial boundaries created by the Dayton Peace Accords, allowing local communities to unite around ecological defense regardless of ethnic or political affiliation. Such solidarity offers a model for decolonial approaches to conflict transformation and peace practice. By centering affected communities and individuals, and drawing on the joint dangers of extractive projects, they can move past tired divisive tropes to generate solidarity that transcends ethnic divisions.

Environmental movements need financial resources, technical expertise, and help to exert political pressure on corporate and state actors. They demonstrate what Horvat calls “transformative agency” – the capacity to challenge and disrupt existing power relations while building alternative forms of democratic participation, whether through green party politics or individual actions. Peacebuilding organizations can provide solidarity and aim to operate according to the same principles. Following Lippman’s approach, this means avoiding the romanticization of communities or dismissing their concerns as parochial but instead treating local knowledge as sophisticated analysis worthy of serious engagement that centers community actors while providing important broader context.

For international organizations and others working in Bosnia and Herzegovina, especially those focused on peacebuilding, it’s important to move beyond solidarity as symbolic support toward relationships that involve resource sharing and mutual risk. This requires supporting environmental movements not only in advocating for climate protection policies but also in the crucial work of monitoring, enforcing, and defending these policies against corporate and political resistance.

This has implications for how peace organizations approach policy advocacy, institutional partnerships, and program design. Supporting approaches to peace may require organizations to advocate for policies that challenge rather than reform existing arrangements, even when this conflicts with approaches preferred by donors or government partners. At the same time, it is a tacit acknowledgement of the need to reform the Dayton system thirty years after its implementation towards a governance structure that is in line with European integration (and thus environmental protection) while at the same time addressing issues of socioeconomic and climate justice within the transition process.

Perhaps this kind of committed decolonial peace work in cooperation with environmental movements may inspire individuals who, to date, have avoided seeking political office to engage more actively beyond informal and formal civil society organizations. Further, it may mitigate the continued outmigration the country is experiencing due to the very corruption and extractive practices that are making a sustainable livelihood in some of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s most environmentally vulnerable communities difficult.

Environmental resistance movements demonstrate that decolonial peacebuilding approaches are not a task for tomorrow, but a necessity that should be supported and engaged with today. Through their activism, they are preserving and imagining a prosperous Bosnia and Herzegovina, one based on a vision of peace based on socioeconomic justice, sustainability, and genuine self-determination. This is the future toward which truly decolonial peacebuilding must orient itself.

Dženeta Karabegović is an Associate Professor at the University of Salzburg where she habilitated in both sociology and political science. Her work explores migration, diaspora, transnationalism, social movements, foreign policy, transitional justice, and the Western Balkans. Beyond academia, she has provided consulting services to international, regional, and local organizations, and regularly guest lectures across and beyond Europe. She works across English, German, and BCS languages.

[1] Borowiecki, M. et al. (2023), “Accelerating the EU’s green transition”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1777, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/bed2b6df-en.

[2] Dogmus, Ö. C., & Nielsen, J. Ø. (2020). The on-paper hydropower boom: A case study of corruption in the hydropower sector in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Ecological Economics, 172, 106630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106630

[3] Lai, D. (2016). Transitional Justice and Its Discontents: Socioeconomic Justice in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Limits of International Intervention. Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2016.1199478

[4] Horvat, V. (2024). Here, at last: Pathways of green politics in the Western Balkans. Heinrich Böll Stiftung.

[5] Transparency International BiH has focused on the impact of corruption on the environment in its most recent reports, especially on misuse of concessions. See concession register here: https://koncesije.transparentno.ba/bs-latn-ba

[6] Hodžić, D., & Ćurak, H. (2022). Daytonitis in Practice. https://doi.org/10.18452/23999

[7] Transnational networks have developed not only in BiH, but across the region. See for example: https://www.balkanrivers.net/en

[8] https://www.frontlinedefenders.org/en/organization/park-prirode-trstionica-i-boriva

[9] See for example: https://www.coe.int/en/web/bern-convention/-/possible-negative-impact-of-hydro-power-plant-development-on-the-neretva-river

[10] Lai, D. (2016). Transitional Justice and Its Discontents: Socioeconomic Justice in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Limits of International Intervention. Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2016.1199478

[11] For all posts, see here: https://lefteast.org/author/peter-lippman/