As the youngest child in my family and the only one born after the war in Kosovo, I experienced these events through a limited lens — only through the stories shared with me by my relatives. These conversations often ended abruptly, as if speaking about the war would take those who had lived through it back in time, rekindling painful memories. Most of the time, they didn’t feel comfortable discussing it and would close the subject with the familiar refrain, “Thank God, those days are behind us.”

In school, the war was relegated to the final chapters of history textbooks, which were rarely covered before the school year ended, leaving much untold.

I come from Gjakova, a municipality where many massacres and war crimes were committed during the war. Less than 40 minutes away from my hometown lies the municipality of Rahovec, which is especially known for the massacre in the village of Krusha e Madhe, which occurred from 25-27 March, 1999.

Although I grew up constantly hearing about this massacre, the reluctance of both my family and the education system to talk about the war had prevented me from learning more about what had happened there. Over time, my curiosity grew, fueled by my studies, several training programs in transitional justice, and my work as a journalist.

This past November, I decided to journey to the village of Krusha e Madhe to visit its Memorial Complex. The site includes the graves of those who were massacred, the 64 individuals who were forcibly disappeared (14 of whom were from the Ashkali community), memorial plaques, and the Krusha e Madhe Massacre Museum, inaugurated in March 2024.

Entering through one of the two doors to the museum, I walk through the history of the village before its siege, followed by displays related to the massacre.

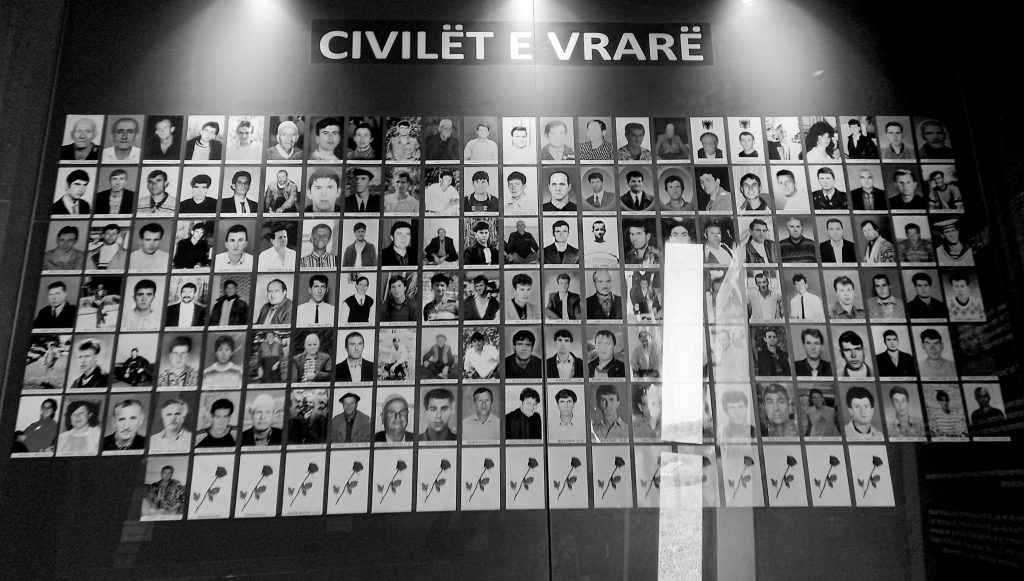

The museum consists of a total of 11 corners: the History Corner, the Fallen Soldiers Corner, the Massacre Corner, the Overview of Damages, Photos of the 155 Murdered Civilians, the Landscape of Memory — Separation of Paths, the Concealment of the Crime Corner, the Media Reporting Corner, the Interviews Corner, the Missing Persons Corner, and the Hope Corner — Return to Life.

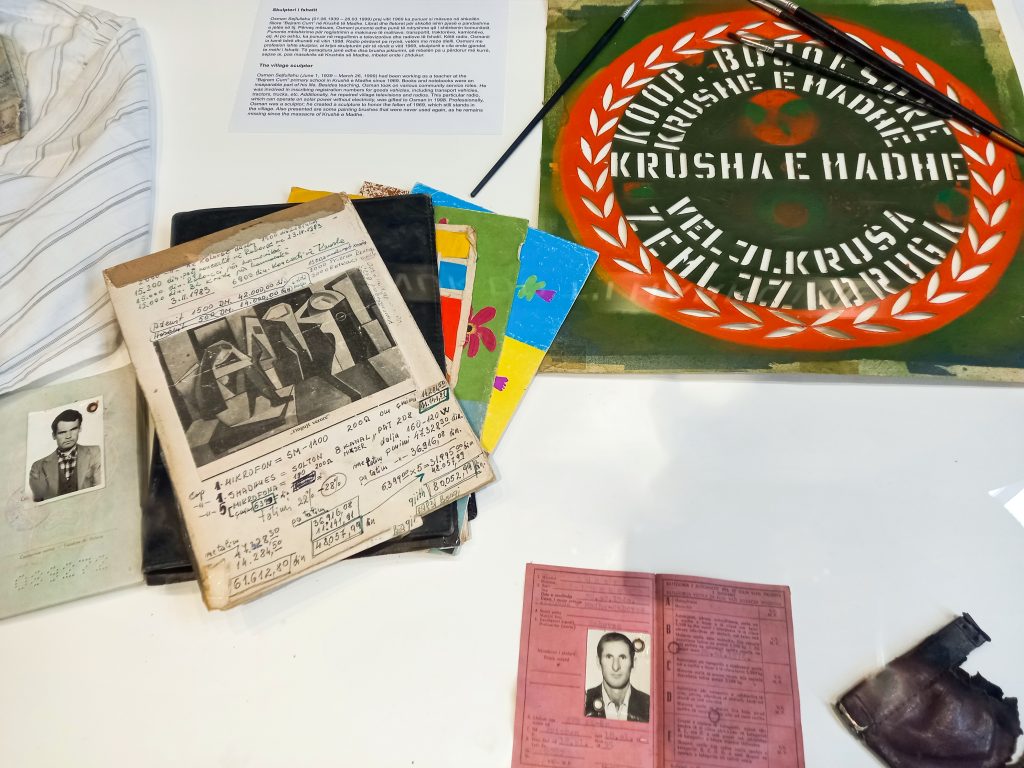

Everywhere I look, my gaze catches dozens of artifacts and personal belongings. According to its guide, Irfon Ramadani, the museum contains over 40 artifacts. These include clothes and items stained with the blood of victims, pieces of weaponry from Serbian forces, photographs of survivors, victims and missing persons, identification tools, glasses, school bags, a child’s crib, and a few other belongings that survived and are still preserved 25 years after the war. The museum also features newspapers showcasing international media coverage of the massacre, as well as televisions displaying the testimonies of those who survived it.

Entering the museum feels like crossing into a place where past and present collide — objects and voices from the past intertwining with a contemporary world compelled to remember and reflect. Among these objects, three in particular have stayed with me, etched in my mind as haunting embodiments of the tragedy of war.

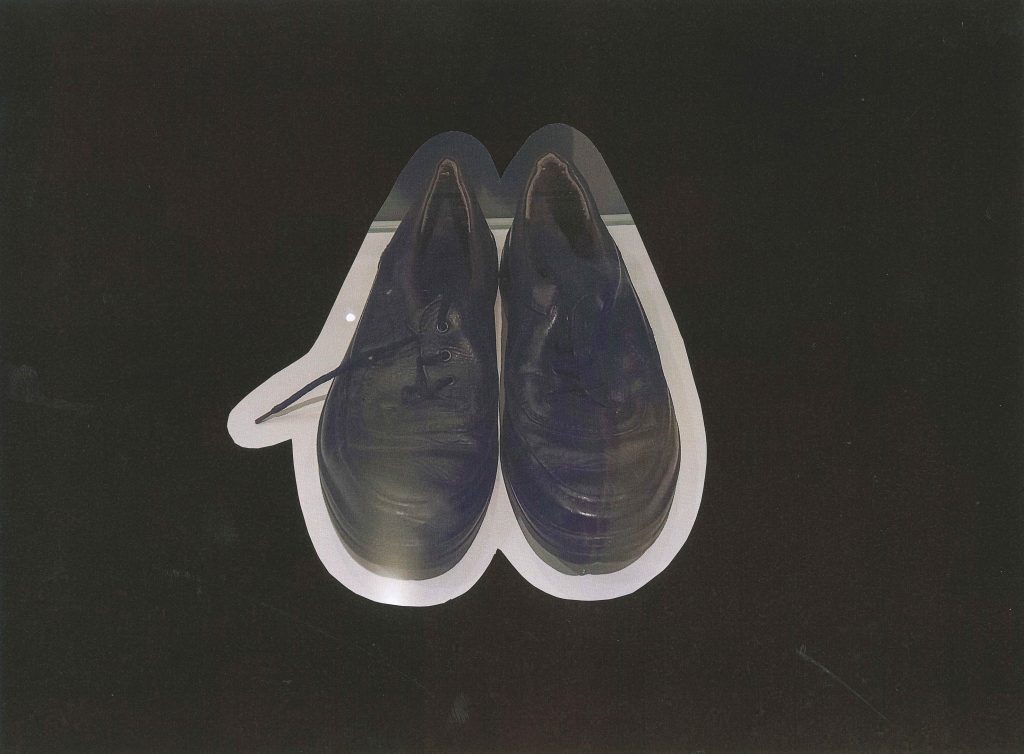

Pointing to a seemingly new pair of shoes, Irfon explains that they belonged to Shani Hoti, who had bought them before the start of the war. “Before the war, buying footwear was quite difficult due to the dire economic situation,” he adds. He recounts how, after purchasing the shoes, Shani left them at home, hoping that, once the situation calmed down, he could wear them for the Bajram celebrations. His wife advised him, “Wear them, for we don’t know what might happen.” Before the war ended, Shani was killed alongside his brother Refki and his father Fetah, leaving behind his shoes — unworn.

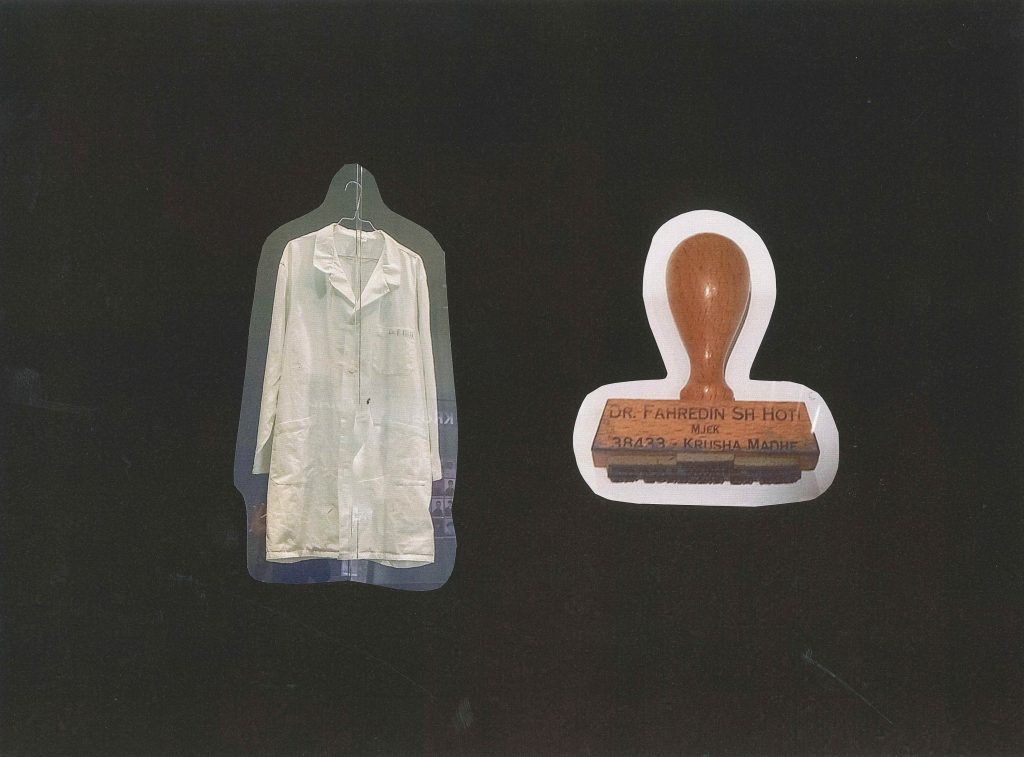

Not far from Shani’s shoes, lies the white coat of doctor Fahredin Hoti, along with his medical seals and his instruments’ sterilizer. “His house served as a secret medical station, where he treated pregnant women, soldiers and civilians. He provided medical care not only at his home but also in the field, reaching the upper part of the village and several nearby villages,” Irfon explains.

On March 26, while Fahredin was providing assistance in a village where the population had taken shelter, a grenade exploded a few hundred meters away, hitting his 14-year-old son, Kreshnik. Upon hearing the news, Fahredin grabbed his medical bag, threw it over his shoulder, and rushed toward his son to provide first aid. At that moment, a sniper shot him, and Fahredin fell to the ground. There, he turned to his medical bag and began to treat himself. While doing so, over the course of one or two hours, he passed away near the body of his son.

While doctor Hoti’s story reflects the strength of a healer in the face of tragedy, the watch of Musli Veseli, also displayed in this museum, quietly holds a story of its own — a story of time frozen during the horrors of war.

Musli, 47 at the time, was taking shelter in the village of Nagac on April 2, 1999, when Serbian forces bombed the village with military aircraft. Two people died in the house where they had sought refuge. The bombing caused the walls of the house to collapse, trapping Musli’s hand under the debris. “As a result, the glass of the clock shattered and the clock’s hands stopped at 2:05. Twenty-two years later, on December 18, 2021, at 2:05, Musli Veseli passed away, at that very same time,” reveals Irfon.

Out of 155 civilians killed, 22 fallen soldiers, and 64 missing persons, Krusha e Madhe counts 241 massacred individuals, 100 of whom were burned. Among the victims are seven children and five women, including one pregnant woman.

As Irfon discusses the loss of lives and the material damages totaling millions, he pauses at a black metal bar. Though not from the wartime, it has been installed in the museum, splitting the space in two. “This metal bar represents how, whenever the population was stopped by Serbian forces, men and women were separated. The women were set free, while the men were taken to be massacred. Men between the ages of 18 and 65, but also boys under 18 who appeared more physically mature, were sent to their death,” Irfon explains. He then adds, “For many, this was the final point of contact, the final memory of their loved ones.”

As I walk past this bar, the sound of rain reaches me, echoing the gloomy weather of the days when the massacre occurred.

The war in Kosovo began on February 28, 1998, following the attack by Serbian forces on the villages of Likoshan and Qirez in Drenica. On March 14, 1999, NATO authorized airstrikes against Serbian military targets. After 78 days of bombing, on June 10, 1999, the entry into force of the Kumanovo Agreement ended Serbian violence in Kosovo, as a prerequisite for the cessation of NATO bombings of Serbian targets. According to data from the Humanitarian Law Center Kosovo, 13,518 people were killed during the war in Kosovo, including 10,794 Albanians, 2,197 Serbs, and the remaining victims from other ethnicities.

It is the last section of the museum, however, that surprises me most. In a museum dedicated to the past, to the violence and the loss, the Hope Corner carves a space for the future, for the history that continues beyond. Glancing over certificates and trophies won by the village’s students and nearly 200 photos capturing special moments from life after the war, visitors can sit on beanbags and take a moment to reflect, surrounded by this tribute to the strength of rebuilding.

The museum ends with a guestbook for visitors to share their impressions, before exiting through a different door than they entered. I feel as if the museum itself encourages me to depart with a sense of clarity and hope, inspired by the Hope Corner, rather than carrying only the painful memories I have witnessed.

By merging historical relics with modern digital tools, this museum creates a necessary space for learning and healing, allowing visitors to engage with the trauma of the past while inspiring hope for a just future. This powerful message, displayed on one of the plaques within the museum, has stayed with me: “After enduring the horrific experiences of war and massacre, the village of Krusha e Madhe has persevered. The people of Krusha have triumphed over the shadow of death. We will never forget, but we have discovered the strength to move forward, to work, create, and live on!”

This story was originally written in English.

Bubulina Peni began her career at KALLXO.com and contributed to Prishtina Insight. She later broadened her expertise in public communication and now works as a freelance journalist, focusing on education, human rights, children’s and minority rights, as well as dealing with the past.