Between emancipation and propaganda, and under conditions of survival

May 2025 marked 80 years since the end of the Second World War (WWII), but in Kosovo, this anniversary passed by without any special commemoration. In general, WWII does not occupy a significant place in Kosovo’s collective memory, which is reflected by the neglect — and in some instances, even the demolition — of memorials and monuments built during the socialist period that commemorate the war.

One reason for this absence in memory is that public attention is mostly focused on the war of 1998–1999. Additionally, the end of WWII in November 1944 was not experienced by the majority of Kosovo’s Albanian population as true liberation. On the contrary, this moment is frequently viewed as initiating what is often characterized as a renewed occupation by Yugoslav forces. Nevertheless, discussions about WWII are not entirely absent.

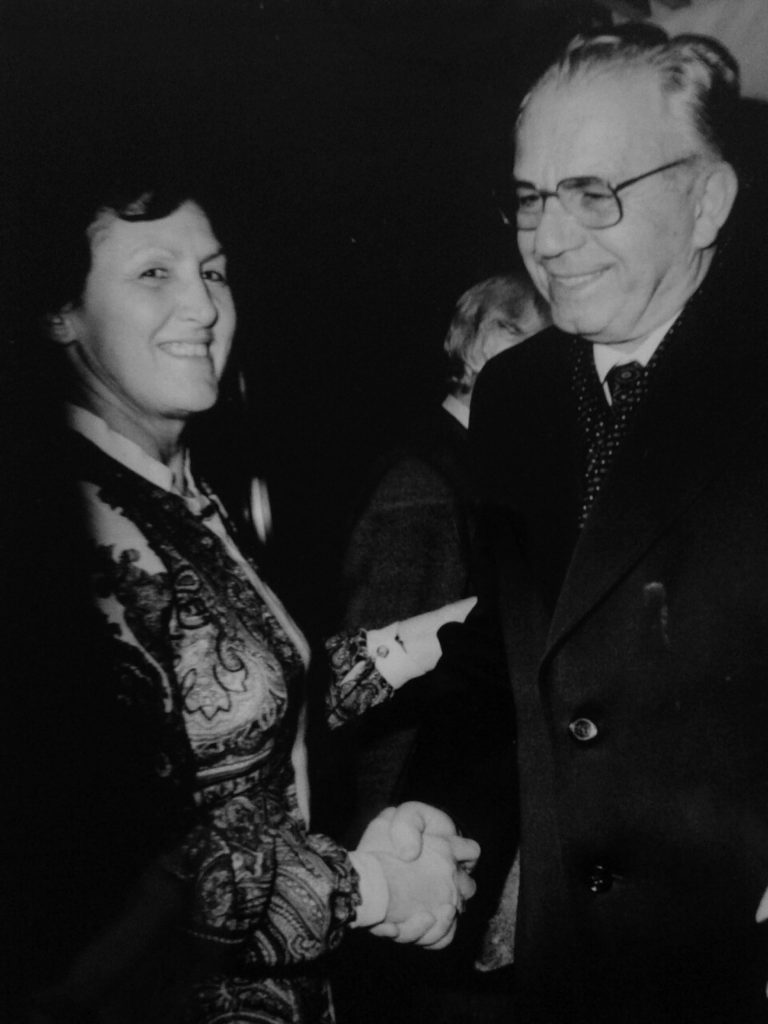

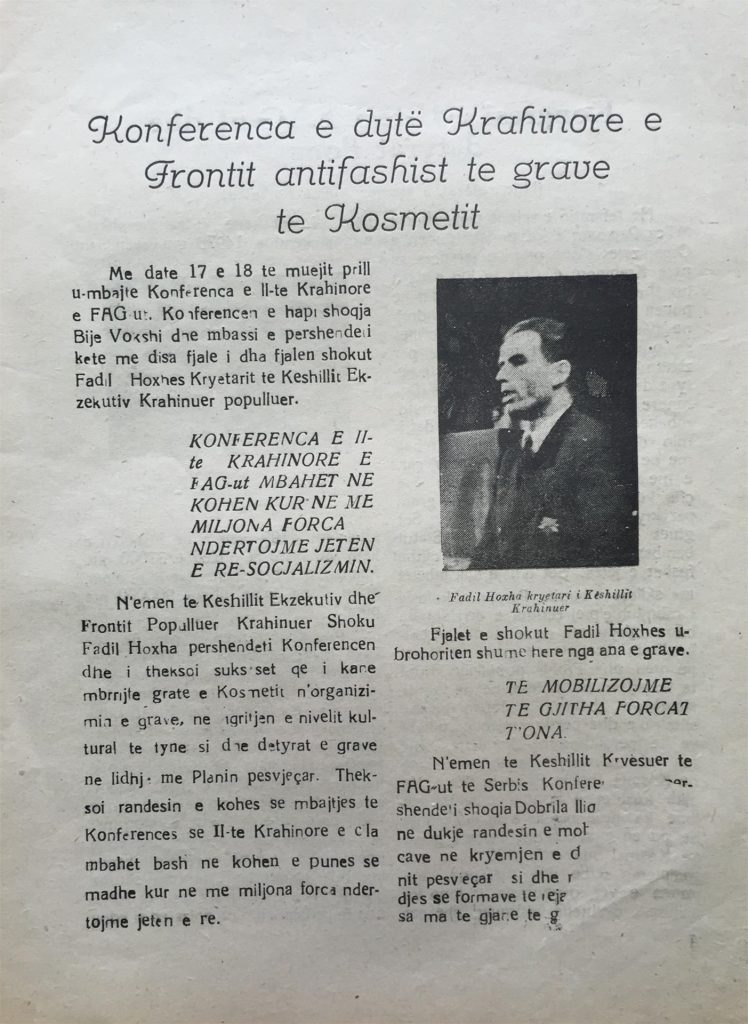

Beyond academic circles, the Organization of Veterans of the Anti-Fascist National Liberation War of Kosovo (OVLANÇ) organizes yearly gatherings related to the anti-fascist struggle. The activities of this non-governmental organisation receive little media attention, but information about them is available on its Facebook page. OVLANÇ is led by Lekë Hoxha, the son of Fadil Hoxha (1916–2001) — a partisan and key political figure in Kosovo after WWII — and of Vahide Hoxha, an important figure in the Anti-Fascist Women’s Front of Kosovo and later as a teacher at the Prishtina Normal School. This year, OVLANÇ’s event, held in late October in Prishtina, focused on “The Contribution and Emancipation of Women in Kosovo since the Anti-Fascist War of National Liberation.”

Although small events such as this one bring women’s narratives back into focus, they do not change the fact that, within the dominant narratives of Albanian historiography, women’s struggles for national and gender liberation — even when present — are not approached through feminist theoretical frameworks.

Among the significant narratives of WWII and socialism is that of the Anti-Fascist Women’s Front (WAFF), Frontit Antifashist të Grave (FAG), known in the Slavic languages of Yugoslavia as the Antifašistički Front Žena (AFŽ), which emerged from the war promising gender emancipation within Yugoslavia’s modernizing project.

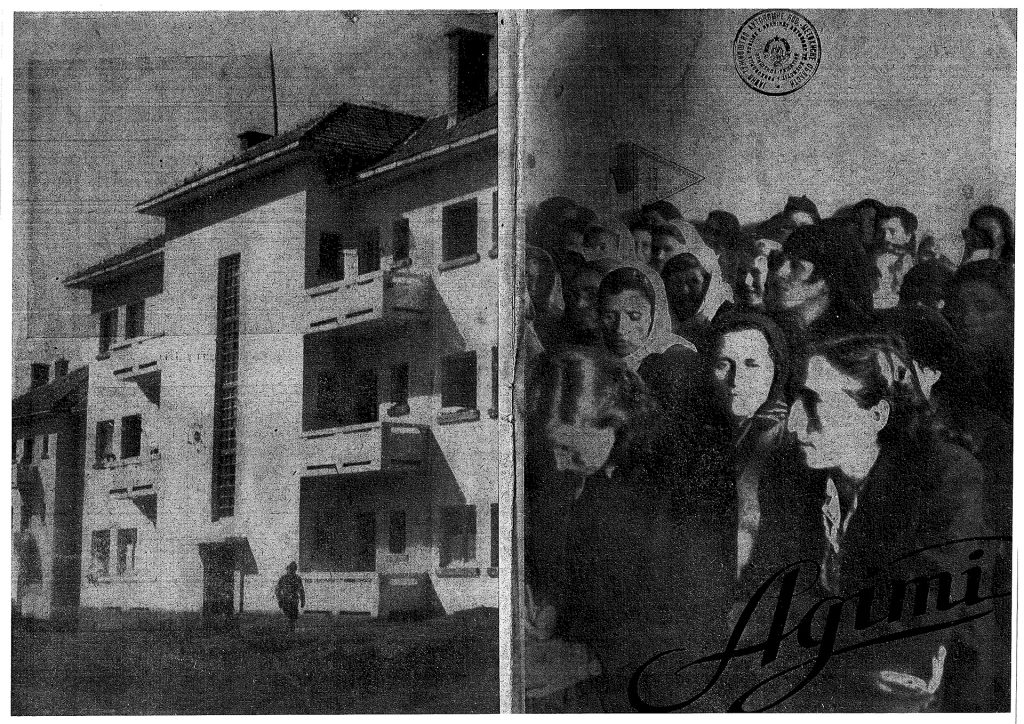

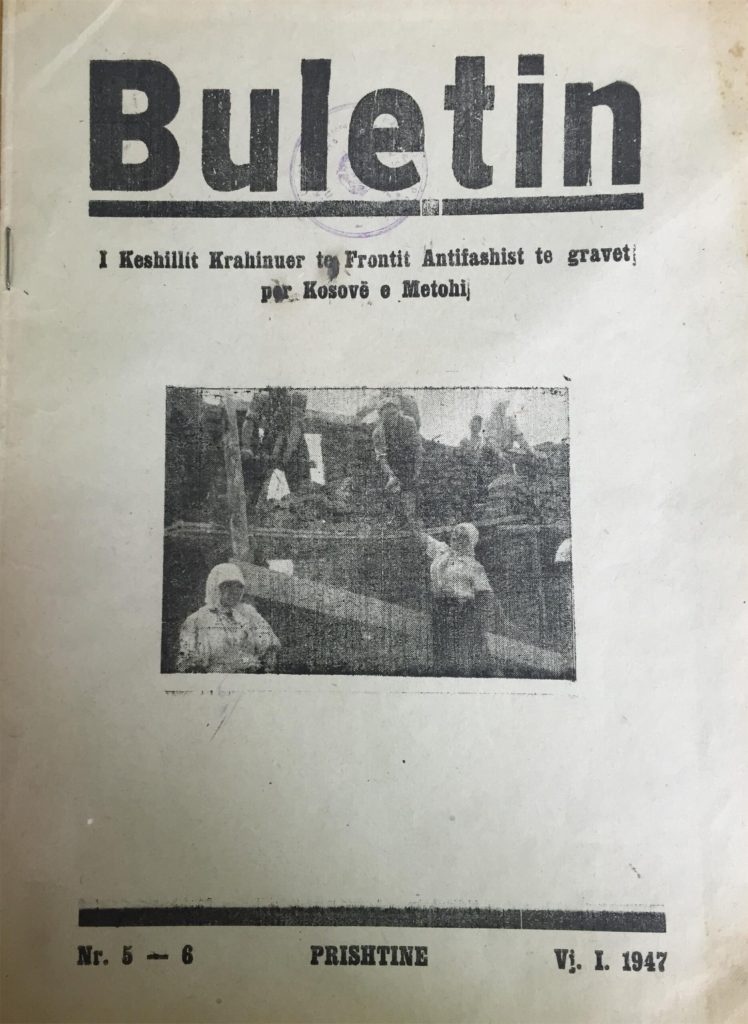

In Kosovo, WAFF is primarily remembered for its post-WWII activities, especially its campaigns to remove the Islamic veil and its advocacy for literacy, particularly among women. WAFF’s printed publications in Kosovo are almost entirely dominated by these campaigns — its bulletins and the magazine “Agimi” (The Dawn). The role and challenges of WAFF following WWII cannot be understood in isolation, especially when their work is viewed relative to the political and economic realities of the time. From this perspective, the dual nature of WAFF becomes visible: the tension between its aims and the means through which those aims were pursued. WAFF’s primary goal was the liberation and emancipation of women, but at the same time, its press provided a platform to promote the state’s repressive policies.

Perhaps this was the only possible way to pursue emancipation — through negotiations with power, a tactic that is not uncommon in other historical and geographical contexts.

The context in which WAFF emerged and operated

In the years preceding the end of WWII, attempts to define Kosovo’s status remained unsuccessful — both at the Mukja Conference (August 1943), where Balli Kombëtar (the National Front) demanded that Kosovo unify with Albania, and at the Bujan Conference (end of December 1943 – early January 1944), where Albanian communist delegates demanded the right to self-determination.

Following the end of the war, Kosovo was annexed by Serbia as part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY).

In Kosovo, various political formations were active at the time. Some joined the National Liberation Movement as part of the war against fascism, in coordination with the Communist Party of Albania and the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. Others were armed anti-communist groups that rejected the idea of liberation within a shared framework with Yugoslavia, due to the earlier repression and colonization carried out by the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Among the actors who refused to align with the communists, the National Front (Balli Kombëtar) stood out, with structures in both Albania and Kosovo. This formation collaborated with fascist Germany and sought the unification of Kosovo with Albania. The collaboration was not based on ideological alignment, but on a shared desire to prevent Yugoslavia’s return. As historian Oliver Jens Schmitt notes in his book “Kosovo: A Short History of a Central Balkan Region”, Albanians accepted assistance from the Axis Powers — Germany and Italy — because they offered protection and military technology to resist the reestablishment of Serbian administration.

While the war concluded, violence did not end; on the contrary, in Kosovo, it took new forms within the emerging political order of Yugoslavia. The most remembered event from this period is the Tivar massacre. In March 1945, Yugoslav forces recruited, mainly by force, around 7,700 Albanian men, whom they divided into three convoys, sending one convoy after the other on a deadly journey toward Montenegro via northern Albania. According to historian Uran Butka, on 31 March 1945, in Tivar alone, partisan forces massacred 1,460 Albanian recruits. Killings also occurred in other locations and especially on the route to Tivar.

Another infamous period, the harshest for Albanians during socialist Yugoslavia, was from 1945 to 1966, under the regime of Aleksandar Ranković — Minister of Internal Affairs and head of the State Security Administration (UDBA). In this period, Albanians experienced economic and political repression and violence, not only because the state sought to suppress any remaining forms of resistance, using this as a pretext to justify repression, but also because the policies themselves were implemented in a violent manner. In her book, “Between Serb and Albanian: A History of Kosovo,” historian Miranda Vickers writes that according to various Albanian sources, an estimated 36,000 to 47,000 Albanians were victims of mass violence and systematic executions carried out by the communists between 1944 and 1946. When the border between Yugoslavia and Albania was closed in 1948, following the split between Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, repression against Albanians in Kosovo intensified because of the support Albanian leader Enver Hoxha expressed for Stalin, a repression that expanded through strict surveillance, interrogations, imprisonment and violence.

Economically, Kosovo was a poor and largely underdeveloped region. Before the war, according to the data of economists and demographers, more than 87% of its population was engaged in extractive agriculture, there were no paved roads, and only 2.6% of households were connected to electricity. Following WWII, Kosovo was still considered poor and, as such, in 1956, it was included in the Fund for Underdeveloped Regions. Conditions changed very slowly. In this Fund, all federal units in Yugoslavia contributed approximately 1.8% of their social-sector income, and the funds were then allocated to four units classified as underdeveloped: Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Nevertheless, the structure of these funds deepened Kosovo’s economic dependency: until the early 1970s, more than 80% of this funding was directed into sectors outside local control — such as energy, mining, metallurgy and chemical industries — meaning the actual economic benefits did not remain in Kosovo. In 1961, the active agricultural population still accounted for 48.6% of Kosovo, and by 1965, around 1,000 villages — roughly 70% of the territory — remained without electricity.

It was within this context of repression that the Women’s Anti-Fascist Front of Kosovo and Metohija, which would later be known simply as the Women’s Anti-Fascist Front (WAFF) — developed its activities further.

WAFF was founded in 1942 and initially worked to mobilize women in support of the Anti-Fascist National Liberation War (AFNLW). In Yugoslavia, it is estimated that around 100,000 women participated as partisans, while around two million contributed in other forms. In Kosovo, WAFF was active in Prishtina, Prizren, Gjakova and Peja, engaging women in gathering aid for partisans, distributing medical supplies, sheltering AFNLW participants and delivering messages.

Following the war, from 1945 onward, WAFF in Yugoslavia focused its efforts on including women in political life, organizing mobilization efforts for postwar reconstruction, expanding education and literacy, and promoting the opening of childcare centers that enabled women to work and gain basic economic independence. In Kosovo, as in other parts of Yugoslavia, WAFF established mechanisms, including a Secretariat, which coordinated activities and delegated responsibilities.

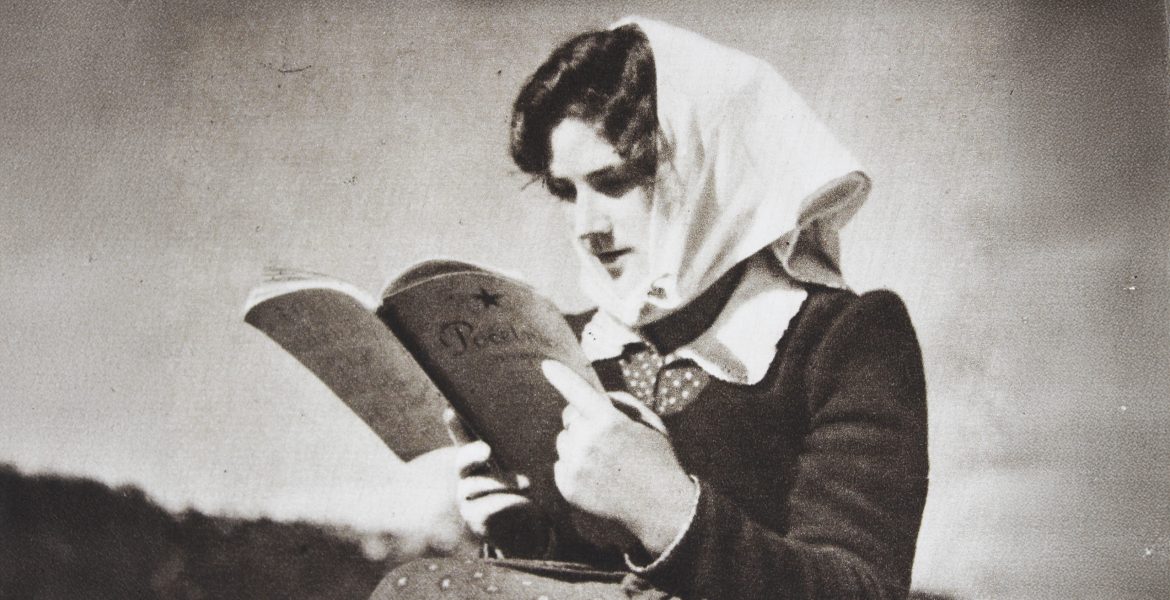

Like elsewhere, WAFF in Kosovo also printed its own publications — bulletins and the magazine “Agimi.” In 1946, its first bulletin was published in Prizren. Naxhije Begolli was its editor-in-chief, alongside an editorial team that included Vahide Hoxha, Vehbije Barbullushi-Ginali, Safete Nimani, Rahmije Dobroshi and Jovanka Ninković. This is considered the first Albanian-language women’s publication in Kosovo after WWII. Many articles were unsigned or marked only with initials. Later, in 1949, the bulletin evolved into the magazine “Agimi,” edited by Vahide Hoxha.

The women who founded WAFF in Kosovo were educated and came from families that supported girls’ schooling. Vahide Hoxha, born Kabashi (1926–2013), was among them. She attended high school in Shkodra during the war and later completed her studies in history after WWII. Her grandfather had been a deputy in the Ottoman Parliament, her father studied in Thessaloniki and Istanbul, and her aunts completed rüşdiye — secular secondary schools established through the Tanzimat modernization reforms of the mid–19th century. This educational background in Ottoman Turkish was significant, given that the Ottoman Empire did not allow schooling in the Albanian language.

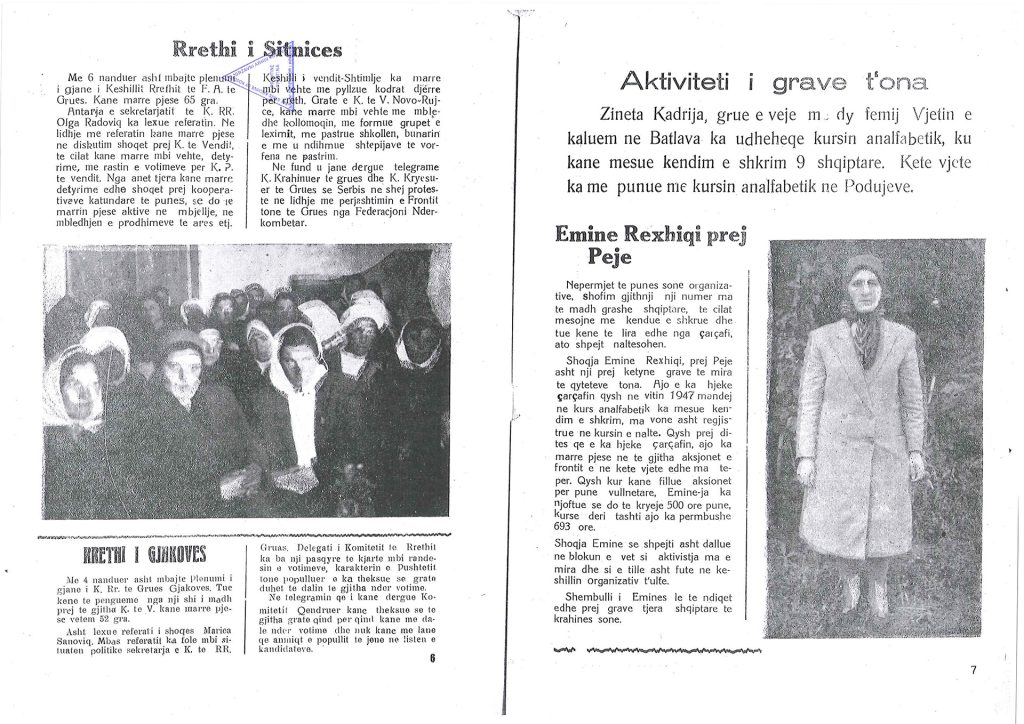

This is why WAFF’s advocacy for education became distinctly important: while it organized literacy courses for the population, particularly women, these efforts were also inclusive, reaching impoverished communities and remote rural areas. Instruction was provided in homes and in organized courses in towns, villages and neighborhoods that taught women reading and writing. Men also attended the courses.

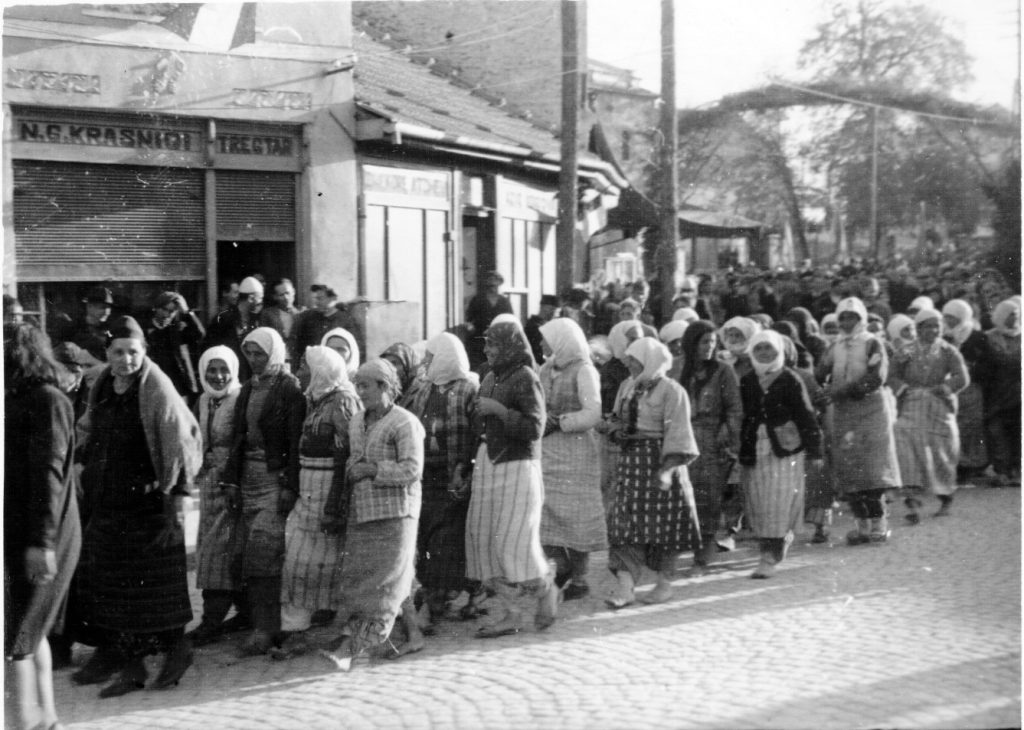

For women who were not literate, WAFF organized reading groups to help them become familiar with the content of their bulletins. The literacy campaigns ran in parallel with the campaigns for veil-removal, and both were part of the larger effort to integrate the region into the socialist project of modernization. During the activities it organized — such as courses in sewing, household skills, wool spinning, childcare and more — WAFF discussed state policies with women.

Campaign for Removing the Veil

Efforts for modernization — that is, a modernist gender discourse that viewed the Islamic veil as an obstacle to women’s liberation — had already begun to take shape in the mid-19th century and during World War I. As early as the 1920s, governments in countries such as Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, the nations of Central Asia, the Caucasus and the Balkans initiated veil-removal policies for the purpose of gender emancipation. In Yugoslavia, the Communist Party similarly sought to break with Ottoman legacies, seeing the Islamic veil as one of its visible remnants.

The veil, which in this period covered both a woman’s hair and face, was described as a “relic of the past” associated with Islamic religious practices that were perceived as oppressive. Not all Muslim women in Kosovo, however, wore the veil. For example, across the Dukagjin plain in western Kosovo, women wore traditional local garments made of linen that they had woven themselves on looms.

During this period, the veil is referred to by various names — ferexhe, peçe, çarshaf, terlik, xharë — which were not merely linguistic nuances or regional variations, but terms indicating different forms of covering. For instance, the çarshaf covered the body, while the peçe covered the head and face. Differences also existed in the textiles used, which likewise revealed social distinctions — between wealthy and poor women — as well as marital status, indicating whether a woman was married or unmarried.

In Kosovo, opposition to full covering — including the covering of the face — did not initially start from WAFF.

During WWII, veil removal was promoted by teachers from Albania who had come to Kosovo to teach in the 173 Albanian schools that had opened during the Italian occupation. Debates in parliament on banning the veil had begun in Albania as early as 1920; authorities had initially tried to persuade the population rather than impose force. By 8 March 1937, however, Albania adopted a law prohibiting the covering of the face, whether partially or fully.

In the early postwar years, the campaign for removing the veil in Yugoslavia was not particularly successful. Historian Drita Bakija-Gunga, who has studied the work of WAFF in detail, notes that this occurred because girls and women remained under the control of the men in their families. In some cases, even after removing the veil, they would later put it back on. There were also cases where women did not wish to remove it at all.

One such example was the case of Didare Dukagjini, who recalls that removing the veil at age 17 — an act encouraged by her father — felt both difficult and dramatic. Didare was never entirely sure why her father urged her to do so: whether it was because of his friendship with members of the Communist Party, because he wanted her to pursue an education or simply because he wished to adapt to the changes of that time.

The story of Didare is closely tied to WAFF and is one of the few well-documented biographies, thanks to the book, “Didara: životna priče jedne Prizrenke” (Didarja: The Life Story of a Woman from Prizren), by ethnologist Miroslava Malešević, who was also the wife of Didare’s son.

Born and raised in Prizren (1930–2006), Didare was first educated in Serbian, since schooling in Albanian was not permitted in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Education in the Albanian language became possible during WWII, when the Italian authorities established Albanian schools. After the liberation, through a teacher-training course, Didare became an instructor for children and their mothers, teaching them reading and writing in Albanian. She later became one of the WAFF leaders for the Opoja and Gora regions. After completing her university studies, which she began in Belgrade and continued and finished in Skopje, she taught at one of the oldest elementary schools in Prishtina, “Vuk Karadžić,” now “Elena Gjika,” and later became a high-ranking official at the federal level in Yugoslavia.

Alongside the resistance of some women, and various family pressures — to either remove or keep the veil — poverty was another factor that slowed down widespread veil removal. Women often used the lower part of the veil, the çarshaf, as a substitute for a coat. Evidence of this is documented in the minutes of a 1950 meeting held in the Municipality of Sharr (Dragash), which are preserved in the Inter-Municipal Archive in Prizren. The minutes reveal the Communist Party engaged in criticism of women who had not yet removed the veil. At the meeting, one municipal official stated that textile materials would soon be arriving in the small town of Dragash, allowing women to sew coats, adding that, “Everyone knows that in Yugoslavia there is work for all, and that everyone can buy food and clothing.”

Similar cases, where women had not removed the veil due to poverty, existed in other parts of Yugoslavia where WAFF was conducting its campaigns, such as Bosnia or what was then known as Macedonia. So, while the authorities were using the issue of women’s emancipation as a propagandistic tool, highlighting the possibilities offered by the new government across the country, they were also denying the economic limitations women faced.

In their efforts to support the removal of the veil, the Communist Party and WAFF also mobilized Muslim religious leaders, who issued a resolution titled “Rezulucion”, published in a 1947 bulletin, outlining the reasons why the veil was considered unnecessary:

“We, the Muslim clergy, who ought to know the Islamic faith best, believe that the unveiling of Albanian Muslim women is not an act against Islam, because Islam does not oppose — nor can it oppose — progress. The best proof of this thesis is that the cradle of Islam resolved the issue of the çarshaf long ago, because it was hindering its advancement. We know that unveiling has accelerated the progress of Muslim peoples, as it has in the Soviet Union, in Albania and in other Muslim countries.”

Furthermore, the “Rezulucion” emphasized what articles in bulletins and in the magazine “Agimi” had also been arguing — that the veil was the main obstacle to women’s education. One method of pressuring Party members to remove the veil involved demanding that they lead by example, beginning with their own mothers, sisters and wives. Failure to comply with this request resulted in expulsion from the Party or financial penalties.

The dissatisfaction of those who opposed this socialist transformation — the so-called “reactionary forces” — was expressed in various ways. In the Llap region, these “reactionary forces” spread slogans such as: “After the çarshaf is removed, the law will demand we take off the plis [white cap] as well,” while the Serbian side said: “Albanians have seen enough of unveiled Serbian women; now it’s time they see Albanian women without the çarshaf too.”

The historian Bakija-Gunga offers no explanation as to how these two “slogans” circulated at the time; nevertheless, they reflect the underlying tensions of the period. On one hand, they reveal the discomfort and insecurity felt by the Albanian population toward state policies, which were understood as a threat to their ethnic and religious identity; on the other hand, they show that unveiling was not perceived simply as emancipatory — as it was framed in official discourse — but rather as an act that sexualized women, whether veiled or unveiled. Through these reactions, ethnic, religious and cultural differences between Albanians and Serbs were also being marked. In this way, Albanian women were homogenized, while the lived realities of women in other regions who did not wear the Islamic veil, or who were Christian, were disregarded.

WAFF publications even blamed the veil for illnesses, including tuberculosis, instead of attributing them to the inadequate conditions within the healthcare system. Following WWII, for example, Kosovo had only 12 doctors, whereas by 1952, there was one doctor for every 8,500 inhabitants. Infant mortality was also extremely high but was attributed to “cultural backwardness” and women’s low levels of education, rather than to structural inequalities such as the inadequate conditions of the health system, poverty, lack of schooling in people’s mother tongue, the consequences of the war and the deep underdevelopment of the region.

Ten years after WWII, tuberculosis remained widespread in Kosovo. According to the 1955 Statistical Yearbook of the People’s Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, a total of 2,724 cases were recorded in 1953, and Kosovo — despite having a smaller population than the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina — had roughly 34% more patients per capita, as well as only five anti-tuberculosis outpatient centers with seven doctors in total, five of whom were specialists. By comparison, Vojvodina had 22 outpatient centers with 24 doctors, including 19 specialists. These figures reflect not only the lack of healthcare infrastructure but also the regional inequalities within Serbia.

On 25 March 1951, a law was passed banning the full veiling of women — that is, the covering of the face. By this point, it was estimated that 90% of women had already removed the veil, but as Bakija-Gunga notes, there were still women who openly refused and continued appearing veiled in public. This was treated as a violation of the law, punishable by a fine of 20,000 dinars or a two-month prison term. After the adoption and implementation of this law, women in some areas, mainly rural ones, substituted the face veil with headscarves. In the name of “freedom,” however, the veil — in whatever form it was worn — had acquired a cultural stigma.

The gap between what the state sanctioned and what occurred in everyday life remained large, but invisible to WAFF publications. WAFF’s press often presented an idealized, unrealistic world aligned with the state policies of the time. In this sense, beyond being a key actor in the major transformations that shaped women’s lives in this period, WAFF — or more precisely, its publications — functioned as an instrument of state propaganda.

This was not unique to WAFF in Kosovo, but was also true in other communist contexts. In Kosovo, however, the tension was sharper due to the colonial nature of the interwar period, the country’s political dynamics, and the violence that occurred during and after the war.

WAFF between gender emancipation and propaganda

The resistance to unveiling in Kosovo stemmed, in part, from the population’s distrust toward the authorities of the time, which is reflected — even if superficially — in the slogans cited by Bakija-Gunga. WAFF was part of the state, and the state was violent. Repressive policies were not directed exclusively at Albanians, but they were applied more harshly against them, especially in rural areas, where resistance to the new communist authorities was believed to be stronger.

In an article from the first issue of the 1946 bulletin, titled “Women Have Understood the Importance of Collecting Grain and Will Therefore Participate Actively,” a conversation among women at a marketplace is described, which is meant to demonstrate support for the agrarian surplus procurement system. It is not specified in which marketplace the conversation takes place.

The women — whom I imagine are sitting on small three-legged wooden stools in front of their fabrics or handmade goods for sale — talk among themselves: “Things are going really well […] the new wheat has come in, and our worries are gone.” Another replies, “Believe me, sister… we must be grateful to our government, because without it, we wouldn’t have made it through the summer.” They go on to describe how last year’s grain collection by the authorities saved them from the “speculators,” as the article terms them, and that these speculators would have impoverished them even further.

The article does not clarify who these “speculators” are, but the term most likely refers to those who disagreed with these measures, which were primarily villagers. One of the women describes how she is convinced that power is now in the hands of the people, and that “those who speak against our government are enemies of the people.” Following this, the article shifts back into first person, as it began, and describes how the author intervenes in the conversation, explaining to the women that the government is taking measures to secure bread, but that everyone’s help is needed — workers, peasants and women — to gather and register the grain so that supplies can be ensured for those who do not produce it themselves.

Another article in the 1947 bulletin, “Let Us Deliver Our Grain Surpluses to Our State,” gives an example from the village of Ponoshec in the Dukagjin region, where women decided to deliver 100% of their surplus grain to the state, calling on other women to do the same: “Let us do everything we can to ensure that our husbands sell their grain to the state, and in this way we will help fulfill our economic plan. We benefit from this. For the grain sold, we will receive money and vouchers to purchase more textiles, clothing, dishes, agricultural tools and other goods.”

One gets the impression from these articles that the government enjoyed broad popular support; however, historical evidence reveals a very different reality.

The collection of “surpluses” was a state economic policy that, through gathering grain and then redistributing it, aimed to achieve social equality. In practice, this policy led to extreme hunger among the poor — who made up the majority of the population — a period remembered in Kosovo as the “bread crisis” and the “bread famine.” Evidence of the coercive implementation of this agrarian policy is also documented in other places, such as Vojvodina.

Mehmet Halimi, a dialectologist who was a child at the time, recounts his memories of this period in the book “Rrëfimet për Kosovën” (Accounts from Kosovo), edited by Fatmir Lama:

“At that time, it was as if we were living under a feudal system, with the difference being that the feudal system only took 10%, the tithe, whereas now, under the communist dictatorship, they scraped the granary clean with a rake. And they gave us a name, supposedly ‘kulaks,’ the wealthy who had and have food, grain, wheat and corn — all large quantities had to be handed over as surpluses. But they didn’t take it only from the kulaks — the wealthy — they took it from everyone.”

In other words, the authorities were not taking only surpluses; as other interviewees in the book recall, the state emptied the granaries entirely, leaving families unable to cook their next meal. The spring was the hardest time, when the “surpluses” were collected, because families were running out of the previous season’s grain while waiting for the new harvest. As Halimi puts it in the interview: “I’m dying of hunger between two loaves — the old one is gone, the new one hasn’t yet arrived.”

To secure their survival, villagers hid grain even though refusing to hand over “surpluses” was punishable by imprisonment and forced labor. Besides the grain, the state collected other foodstuffs — beans, eggs, anything people relied on to eat — as well as materials like wool used for clothing. The accounts of torture and violence carried out during these collection campaigns — for grain, food and essential materials — are chilling.

Against this backdrop, the role of WAFF appears almost contradictory: a leading force in the struggle for women’s emancipation, education and employment, yet at the same time part of a state apparatus that was denying even bread to rural communities.

From today’s perspective, when taking into account the violent context of the time, the WAFF propaganda articles appear to be negotiating with power. This must have been a form of survival, beyond political or ideological convictions — especially considering that the authorities of that time, particularly after the changes of ’48, did not spare even Albanian communists from imprisonment, even those who had family members as high-ranking officials.

For example, Didare’s brother, Enver Dukagjini, was imprisoned for five years at Goli Otok in Croatia by the authorities, a political prison used by Yugoslavia between 1949 and 1989 to confine those labeled as enemies and opponents of the party. In Malešević’s book, Didarja recalled that at a Party branch meeting, Enver had raised the issue of the ban on using the Albanian flag and the removal of flags from the graves of partisan martyrs. Oral histories also recount the imprisonment of Zenel Kabashi — the brother of Vahide Hoxha — because he refused to register as Turkish at a time when Albanians were being pressured not to register as Albanians in the 1953 census.

Didare described that period as a time when “One eye in your head could not trust the other.” While neither her husband, a high-ranking party official, nor she herself had played any role in her brother’s imprisonment, neither had investigated what had happened. The Ranković era was one of strict control. Years later, after Enver’s release, Didare and her husband learned that someone who had posed as a “friend” had in fact been a UDBA informant.

WAFF was dissolved in 1953, after nearly a decade of activity, because its work was no longer considered necessary or desirable. Even the central leadership of WAFF itself believed that maintaining a separate women’s organization risked isolating women from broader social work and created the perception that their issues were distinct from other socialist projects. This was justified by the claim that gender equality had already been achieved, even though many of the laws guaranteeing equality, at least formally, would be passed later. In her own account, Didare notes that resistance to WAFF came from “above.” Still, I think that whatever degree it came in, resistance also emerged from the societal level, at least to the earlier work of WAFF in the years following the war.

Despite the various forms of resistance to WAFF, from whichever side they came from, the achievements of the organization were significant. Didare herself was astonished by what had been accomplished because, as she put it, WAFF’s activities shook the foundations of the system they lived in. On a TV program years later, after the last Kosovo war, Vahide Hoxha emphasized the difficulties of the time, saying that “all things were lacking,” and that anyone writing history must closely examine context and circumstance. Most important — and indisputably — was the achievement of educating girls and women, even if through pressure.

In this context, turning our attention to WAFF and their work allows us to see the past not as a linear path toward progress, but as a contingent process intertwined with political and economic tensions, inequalities and violence.

Feature image: Author’s archive

Elife (Eli) Krasniqi is an anthropoligist and writer.

This article was originally produced for and published by Kosovo 2.0. It has been re-published here with permission.