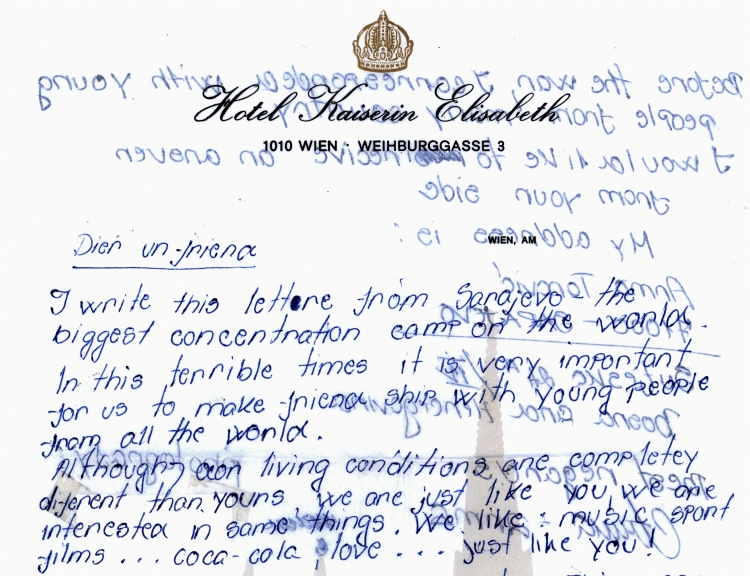

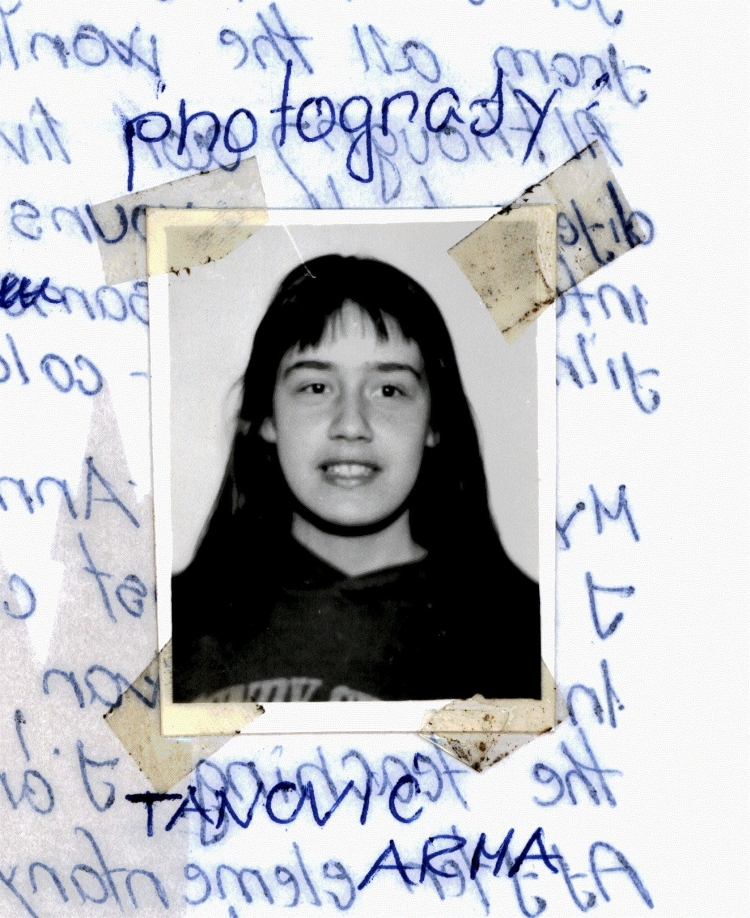

“Sarajevo, the biggest concentration camp in the world,” wrote Arma Tanović at the age of 15. Arma was one of the Sarajevan kids and teenagers, who, a year into the siege, sent letters to their American pen pals, in which they introduced themselves and their daily challenges hardly imaginable for others, and asked their unknown friends to do everything they could to stop the war.

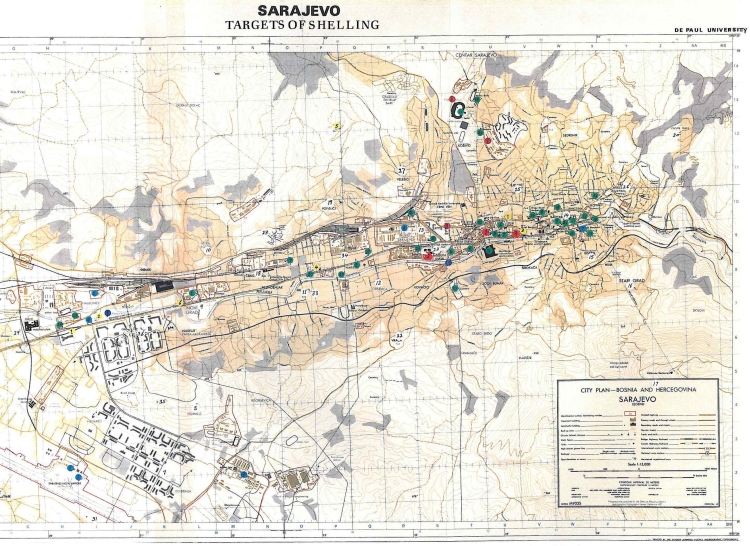

The first shell shot by the Bosnian Serb Army from the surrounding mountains exploded in Sarajevo on April 5, 1992. Although the cessation of hostilities was prescribed in an agreement of October 5, 1995, and reinforced in the Dayton Peace Accords signed on December 14 the same year, the siege officially ended only on February 29, 1996. Throughout these 1,425 days, the city recorded an average of 329 shell impacts daily, with a peak of 3,777 on July 22, 1993. The green dots on the map below indicate targeted and damaged or destroyed civilian and industrial infrastructure, with universities, colleges, and schools among them.

Map of shelling targets in Sarajevo

Map of shelling targets in Sarajevo

Blue: military, UN; Orange: government, presidency building; Red: hospitals, medical complexes; Yellow: media, communication;

Dark blue: bridges; Green: civilian and industrial targets; White: suburbs, quarters of the city

(HU OSA 304)

It is estimated that 15,000 children were wounded and a total number of 1,200–1,500 were killed during the battle of Sarajevo. A memorial for children victims, bearing children’s footprints on the bronze ring covering the circular basin as a symbol of their eternal presence, was erected in Veliki [Great] Park in the city center in 2009–2010. There are 521 names of killed Bosniak, Croat, Serb, Jewish, and Roma children inscribed on the adjacent seven aluminum cylinders.

Veliki Park, Sarajevo

Veliki Park, Sarajevo

(Photos: Csaba Szilágyi, December 2019)

Published in May 1994, the final report of the UN Expert Commission on Investigating War Crimes in former Yugoslavia—preserved in the holdings of Blinken OSA—quotes a UNICEF study claiming that the siege left 65–80,000 children psychologically traumatized by that date; 40% of them had been directly shot at by snipers, most notoriously on Sniper Alley, 51% had seen someone and 39% had seen family members killed, 19% had witnessed a massacre, 73% had their home attacked or shelled, and 89% had lived in underground shelters.

To ease on living conditions amidst destruction, terror, and lack of basic supplies, dozens of international organizations provided support to local initiatives. The Sarajevo Water Project, sponsored by the Open Society Foundations (OSF) and led by the legendary disaster relief expert Fred Cuny, restored the water supply system by smuggling in and assembling water filtration components from the US. Among others, OSF also initiated, as it is revealed from the records, the Open Society City of Sarajevo, a program to preserve the city as a unique phenomenon, and promote its cultural renewal. The Sarajevo Education Project aimed at restoring education during the siege, through school rehabilitation, distribution of textbooks, and printing a children’s magazine entitled Voice of Defiance, distributed in 1,800 copies. In cooperation with UNICEF and under the leadership of the prominent law professor Zdravko Grebo, Radio Zid [Wall] was established, whose Colorful Wall Program was a 90 min daily show for and compiled by children, including news, distance learning, and entertainment programs.

Sarajevo Education Project news briefs, Colorful Wall Program brochure

Sarajevo Education Project news briefs, Colorful Wall Program brochure

(HU OSA 211-0-2)

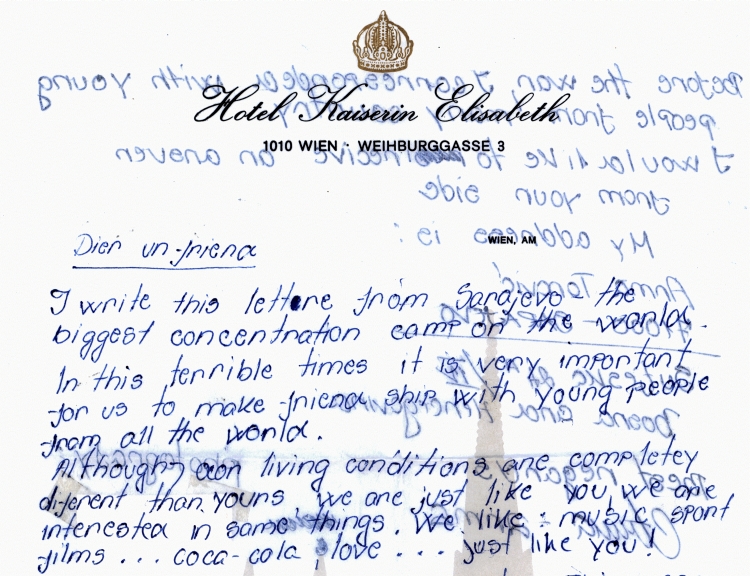

The Pen Pals for Peace Program facilitated exchange of letters between schoolchildren in Sarajevo and Harrisburg, PA. By the end of August 1993, some 400 letters from the besieged city, many with photographs, elaborated drawings, and ornamented envelopes, made their way across the Atlantic; 112 of them ended up at Blinken OSA, the final repository of OSF’s documents of historical value. After having described and preserved them for years, Blinken OSA digitized the letters, and returned the originals where they belong: to the war-affected community of the city. They were donated and added to the permanent collection of the War Childhood Museum (WCM) in 2019.

From left: Amina Krvavac, Director/WCM, Jasminko Halilović, Founder/WCM, Csaba Szilágyi, and József Gábor Bóné, Blinken OSA

From left: Amina Krvavac, Director/WCM, Jasminko Halilović, Founder/WCM, Csaba Szilágyi, and József Gábor Bóné, Blinken OSA

WCM and Blinken OSA agreed to try to contact the authors of the letters, asking them to reflect on their writings and war experiences in general, and, if they consented, to exhibit the letters in the museum in the near future. Arma Tanović-Branković, who is a drama teacher in her native Sarajevo today, was among the first people to react to the call of WCM, and agreed to talk publicly about her war childhood, moreover, she even read out a few excerpts of her choice from the letter. Her personal story emerging from this archival document will certainly have a social life on its own, and contribute to “a shared and shareable ‘public language of grief’—affect that engages with the losses and remnants of the catastrophe.” (Arsenijević, Husanović and Wastell)

According to Jasminko Halilović, founder of WCM, “A war childhood is when you have a crush at school, and then she is killed by a shell.” Undeniably, the children’s letters talk volumes about living in constant fear and danger, killed friends and relatives, and lack of food and other commodities, when normal activities like playing, outing, going to movies were disrupted and replaced by tactics of survival, including fetching water and woods. But defiance and courage also transpires from their lines, as Arma phrased it, “Our existence is very, very difficult but we have love, pride and hope: that’s our arms.” They express deep affect when they write about hating war and disliking mathematics; bad dreams of feeling miserable and powerless ("I know that my voice hasn’t power in the world") or good dreams, like receiving a food parcel from abroad or imagining the streets packed with children and no shelling at all; and sentiments of nostalgia in describing Sarajevo as a beautiful town, the “Olympic city before the war,” which they would leave under no circumstances.

Excerpts from Arma Tanović’s letter

(Blinken OSA)

But what does it mean to write letters to the outside world during the longest blockade in modern warfare? Even if one does not like to write letters? An effort to entertain a sense of normality. Risk. The danger of being bombarded, while consuming fuel that was scarce. It means documenting, recording events and experiences, emotions and longing. Something one can reflect upon. “The acts of witnessing and narrating often serve as the bridge between one’s survival and a life after catastrophe.” (Tumarkin) On April 5, the anniversary of the beginning of the siege of Sarajevo, we remember these small witnesses, and their peers who did not live to witness.

Source: http://www.osaarchivum.org (Bliken OSA)

Author: Csaba Szilágyi