I graduated from primary and secondary general education school a decade and a half ago. There was no time to learn about our contemporary history in any of the final grades shortly before the end of the school year. That, combined with the fact that even back then I was already interested in and had the privilege to meet different people from all parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, gave me the chance to learn about the events from the past war in a more unbiased manner and not to see the 1990s events through a one-sided, biased prism of auto-victimisation.

Many years later, I found out that the lack of classes focusing on this subject was a recommendation made by the Council of Europe in 2000. The purpose was to temporarily stop the teaching about the 1992-1995 period in Bosnia and Herzegovina, until historians, supported by international experts, do not devise a common approach to teaching about this period at schools. Unfortunately, this recommendation expired in 2018, the 1990s returned to the curricula, and since there was no consensus on how to teach about these topics, they became a tool of daily politicking and feud with others. Such a situation generally failed to contribute to facing the past, peace building and a better understanding. Lessons about the last war directly contribute to a ghettoisation among the communities in Bosnia and Herzegovina and create tensions among the youth that had not even been born during the war.

Slight changes to the curriculum in the entity Republika Srpska opened up these questions, but also the fact that such a curriculum existed, including also the textbook ”History”, written by the author Dragiša M. Vasić in 2022, which has been used for teaching purposes in this entity for several years already.

While leafing through the textbook and analysing teaching units about World War II, I already find the expected equalisation of partisans and the Chetnik movement, as the author states the following: ”In 1941, in addition to a Chetnik movement in Yugoslavia, another antifascist movement developed.”[1] This thesis, just as insisting on a number of 500,000 to 600,000 persons killed in Jasenovac, in spite of a revision of history during which it was established that this number is significantly lower, namely between 90,000 and 100,000 persons[2], constitutes introducing historical revisionism with a bang. Its basic thesis is the age-long suffering and suppression of the Serb people, along with a permanent disregard for facts. Falsifying facts from World War II is in a way an alibi and justification for everything that was happening during the 1990s.

While speaking about the political and social crisis in Yugoslavia and introducing Slobodan Milošević, who opened up the ”Serb issue” the author states the following: ”It was a matter of time when Serb politicians would decisively ask the question about a change of their position on behalf of their people, broken and humiliated by the 1974 Constitution and the persecutions in Kosovo.”[3] The author is here fully neglecting the fact that back then, Serbs were the most numerous people in Yugoslavia and that Belgrade was the capital from which the country was managed and in which important decisions were made.

The thesis that ”Serbs were in favour of preserving Yugoslavia, because otherwise they would be split into several states, but they received no support of the West for the defence of Yugoslavia”[4], on the one hand supports the idea of the Great Serbia, and on the other hand it confirms the old, well-known thesis about the wars in the 1990s, namely the one of ”who turned us against each other”. However, the author very soon goes over to a detailed analysis and, according to him, the greatest issue in Bosnia and Herzegovina is the fact that, as a result of Tito’s and Kardelj’s policy, Yugoslavia was decentralised and turned into a sum of one-nation states, and that in 1971, the number of Muslims in Bosnia and Herzegovina surpassed the number of Serbs. The author emphasizes that even back then ”there were warning signs that the political representatives of Muslims would be against Serbs and Croats and would claim the whole country for themselves.”[5] He then states that during the 1990s, following a violent secession supported by the USA, Germany and the Vatican, as well as after Serbs were denied their right to self-determination, Yugoslavia dissolved in a series of civil wars. Here, he fully left out the fact that the turnout during a referendum for the independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina amounted to 64.14% of inhabitants, and that out of the total number of valid ballots, there were 2,061,932 or 99.4% votes in favour of independence, that 6,037 or 0.29% of persons voted against it, and that there were 5,227 or 0.25% invalid ballots. While ignoring the fact that most Serbs refused to express their opinion in the referendum, the author points out that ”most Muslims and Croats voted for the independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina on February 29 and March 1.”[6]

There is a stream of lessons about the contemporary history and the author is describing the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which he calls a civil and defence and liberation war, while at the same time leaving out elements of aggression against Bosnia and Herzegovina. On the margins of textbook pages, there is a range of textboxes with glorifying biographies of Slobodan Milošević, Radovan Karadžić, Ratko Mladić, Milan Tepić, Patriarch Pavle, etc., focusing on their contribution to the ”liberation” of the Serb people. It is furthermore stated that Karadžić, Mladić and Milošević were extradited to the International Criminal Tribunal in The Hague, but without giving any reasons for this or referring to judgments and genocide, which, in addition to representing a distortion of court-established facts, also constitutes an invitation to not comply with these judgments. A biography of Biljana Plavšić, the second president of Republika Srpska and the only woman on trial before the Hague Tribunal, who signed a plea agreement with the Tribunal in 2011 and served an eleven-year prison sentence, is missing. The author obviously has issues with women or disobedient women.

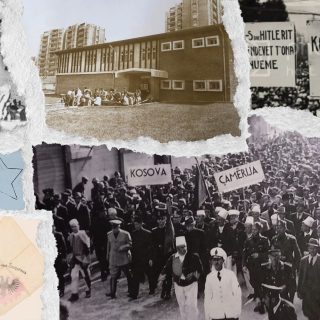

However, although he is disobedient from the perspective of the author, Alija Izetbegović has not been left out. He is described as an Islamic theologist and politician, who was an active member of the pro-Hitler organisation ”Young Muslims” in his youth, which is again a distortion of facts, since ”Young Muslims” have never been a pro-Hitler organisation. Although the author has a continuously ambivalent attitude towards Yugoslavia and communists, he points out that Izetbegović was imprisoned and convicted because of the ”Islamic Declaration” in which he promoted a state based on the Qur’an. [7]

In the lesson about the 1990 wars in Yugoslavia, the fact that a genocide was committed against Bosniaks in Srebrenica has been left out. This is relativised by listing all the places in which crimes happened, and putting Srebrenica first. The chapter ends with the capture of Srebrenica and Žepa by the Army of Republika Srpska, the fall of Republika Srpska Krajina, the conquest of the southern part of Bosanska Krajina by the Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which endangered Banja Luka, followed by the Dayton Peace Agreement. It is also pointed out that the war was marked by the interference of the international community, which is put in quotation marks by the author. The author introduces the term Bosniaks when writing about events from 1994 and 1995, explaining it as follows: ”Croats and Muslims/Bosniaks were unwilling allies.”[8]

In the teaching unit ”Republika Srpska in the Dayton Bosnia and Herzegovina”, students are explained, among other things, that the international community is mostly one-sidedly supporting only Bosniaks, that Bosniaks wish to centralise Bosnia and Herzegovina in order to achieve predominance, and that foreign and Bosniak judges frequently overrode Serb and Croatian judges in voting and that they also dispute the coat of arms, hymn and Day of Republika Srpska.

Such an ethno-centric and malevolent approach to events from the 1990s, which neglects or distorts facts and creates a parallel world, indoctrinates young people and prevents them from accessing sources of court-established facts and relevant war experiences and stories. Had the teaching units been presented during my own education in the manner in which Dragiša Vasić presented them in the textbook ”History” for the 9th grade, I believe that it would be very difficult later on to accept the fact that a genocide happened in Srebrenica, that Ratko Mladić and Radovan Karadžić are war criminals, that a centralised Bosnia and Herzegovina that they wish absolute power over is not a claim of all Bosniaks, that Chetniks were not a liberation army, and many more. I would not know that historic revisionism is a distortion of historical facts for the purpose of spreading dominant policies and narratives, and I would be unable to recognise it, as opposed to revision of history, which is a positive practice of revising existing facts based on new findings. Indoctrinated by such content and lacking skills for a critical examination and thinking, trusting the school, because the school does not lie, it would be very difficult for me to connect to my Bosniak and Croatian peers, convinced that they wish to trick, manipulate and instrumentalise me.

For years, I have been judging young people who are greater nationalists than their parents, those that glorify war criminals in the street, during football games and wherever they find a place to do so, and now I feel sorry for them. I would like to apologise to every non-Serb child living in the entity Republika Srpska that has no right to learn about their group of national subjects, as well as their parents, because the political and intellectual elite voted by members of my people created such an educational system.

Vanja Šunjić is a journalist, activist and writer. She focuses on contemporary art and culture of resistance, examines new perspectives and common denominators of a common cultural space, possibilities for facing the past and creating a vision of a common future. She writes for several national and regional media outlets, and she also publishes literary and film reviews.

[1] Vasić D., Dragiša, Istorija za 9. razred osnovne škole (History Textbook for the Ninth Grade of Primary School), JP ”Zavod za udžbenike i nastavna sredstva” a.d., East New Sarajevo, 2022., p. 129.

[2] https://www.slobodnaevropa.org/a/ivo-goldstein-jasenovac-logor-/29198835.html, 20.09.2024.

[3] Ibid, p. 169.

[4] Ibid, p.178.

[5] Ibid, p.170.

[6] Ibid, p. 185.

[7] Ibid, p. 186.

[8] Ibid, p. 186.