How simplified and exclusionary storytelling impacts generations.

I still remember the first Yugoslav film I watched about Kosovo when I was about 13 and the great discomfort it stirred in me. It was the 1989 film “Boj na Kosovu” (Battle of Kosovo), directed by Zdravko Šotra. I had found it after hours of scouring the internet searching for cinematic depictions of Kosovo and its history. Born in London to Kosovar parents, I felt a strong need to see my country represented on the big screen. While I resonated with popular films I watched throughout my childhood and teenage years, most films I found that depicted Kosovo in the West focused only on the most recent war in Kosovo (1998-99).

I knew the war and the political instability in Kosovo during the ’90s had been the sole factors that made my parents leave their homes indefinitely. But as I got older, my need to see Kosovo and its people represented beyond the war grew stronger. I wanted to watch a film where people had names like mine, where people shared identities similar to mine and had historical experiences that mirrored my own family’s story.

Absent Albanian narratives and 1990s nationalisms

“Boj na Kosovu” was probably not the best place for me to start. This film’s plot centers around the Battle of Kosovo (1389), a battle between Serbian Prince Lazar and his army of Serbs, Bosnians, Albanians and Wallachians against an expanding Ottoman Empire under the command of Sultan Murat I. The film was released against the backdrop of an increasingly oppressive Yugoslav regime that, with the revocation of Kosovo’s autonomous provincial status in 1989, instigated a wave of systematic oppression against Albanians. This led to nearly a decade of human rights abuses in Kosovo, eventually culminating in the 1998-99 war.

“Boj na Kosovu” left a lasting impression on me, though for all the wrong reasons. It depicted a Kosovo that was unrecognizable to me, my family, and to everyone I knew from Kosovo. It felt like the film was made with a specific agenda: to undermine Kosovar Albanian identity, narratives and our collective historical connection to Kosovo.

The film presents the Battle of Kosovo through a Serbian nationalist lens, heavily drawing from mythological narratives found in the “Kosovo Myth”, an ideology that fueled the growth of Serbian nationalism in the 19th century. For example, both the myth and film present Prince Lazar as a martyr who sacrifices himself for the Serbian people, securing them a sacred place in heaven. Consequently, the film centers exclusively on Serbian figures, omits Albanian perspectives and lacks historical accuracy.

By excluding Albanian figures and perspectives — particularly in a film released in 1989 — the narrative serves a propagandistic purpose aimed at undermining Albanian identity and historical presence in Kosovo, both in the Middle Ages and in contemporary times. This selective storytelling creates a one-sided portrayal that reinforces Serbian nationalist views while erasing the roles of Albanians and other ethnicities in Kosovo’s history. But historians such as Noel Malcolm acknowledge that Albanians and other ethnicities were present in Kosovo during the Middle Ages.

This film induced difficult questions within me and it wasn’t until I engaged more deeply with Kosovo’s history that I saw how film was yet another method used to perpetuate an unreflective depiction of Kosovo and its people. This initial exposure to Kosovo in film fostered a critical awareness of its representation throughout the 20th century. Given Kosovo’s precarious historical position during this period, cinematic portrayals of its people, stories, and experiences often relied on external assumptions and unexamined depictions.

This sparked a journey of discovery, leading me to explore more of Kosovo and its people depicted through film — what I found left me with mixed feelings.

Oversimplified narratives and historical stereotypes

I wanted to watch a film produced by a Kosovo-based studio in Yugoslavia to see whether these depictions would be more representative. The first film on my radar was “Uka i Bjeshkëve të Nemuna” (Wolf of the Accursed Mountains), a 1968 film directed by Miomir “Miki” Stamenković. The film follows Uka, played by actor Ljuba Tadić, an Albanian man living in the Accursed Mountains of Kosovo, who faces considerable challenges when his only son, Jahid, becomes a fascist collaborator during World War II.

Uka is caught in a blood feud, a central aspect of the Kanun — the Albanian customary code of conduct. I recognize the significance of this film as a feature representing Albanian culture in Yugoslavia, but I also have many issues with it. The portrayal of Albanian people living in remote villages and engaging in highly patriarchal customs, concerned only with honor and tradition seems like a simplistic and reductive representation.

I acknowledge that these aspects have been significant parts of my culture, but this film portrays a singular view of Albanian culture in Yugoslavia — emblematic of a time when no other depictions of Albanians existed. The film’s emphasis on rigid cultural practices contrasts sharply with my cultural expression.

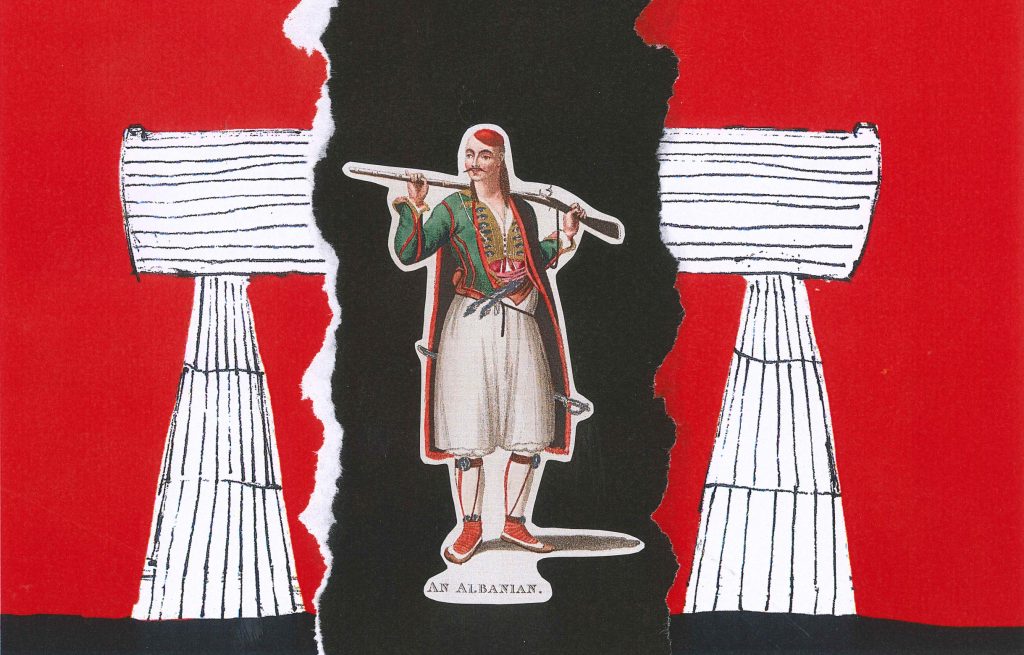

Uka is reduced to an oversimplified, romanticized figure, reminding me of the “Noble Savage” trope that appeared in Western literature from the 16th century onward. Historically, this trope was used to represent Indigenous communities as pure and untouched by modernity — a portrayal that may seem positive but carried a deeply problematic agenda.

Western writers used this trope to romanticize Indigenous communities, commodifying them as static historical artifacts rather than complex individuals. These portrayals frequently served to glorify Western colonial endeavors globally. In the context of socialist Yugoslavia, the character of Uka similarly aligns with the broader socialist political agenda. Uka is depicted as an honor-obsessed, primitive yet “good” Albanian who grapples with his son’s decision to collaborate with fascists.

Though the film was written by two Albanians, Abdurrahman Shala and Murteza Peza, it still displayed a degree of exoticism regarding Albanian cultural practices. By portraying the Kanun and adherence to it as both “strange” and “exotic,” removing it from its broader historical and cultural context, yet “entertaining” for a Yugoslav audience, the film juxtaposes Albanian people and culture against a modernizing Yugoslav society in the 1960s. It also commodifies Albanian culture in Yugoslavia, presenting it as something to merely observe and be intrigued or entertained by but not engage with in a meaningful way.

A similar phenomenon affected Roma culture and people. According to researcher Natalija Stepanović, while “newly introduced Yugoslav cinematic heroes were depicted as embracing modernity,” Roma were consistently excluded from narratives of progress. Albanian communities, like Roma communities in Yugoslavia, were similarly commodified for their cultural contributions but often depicted in a static, marginalized way and portrayed as “backward.” These portrayals positioned them outside the sphere of progress, reinforcing stereotypes that limited their representation to outdated, traditional roles, rather than recognizing their dynamism or contemporary complexities.

Anti-Albanian posturing in film has played a role in how Albanians were seen in Yugoslavia. In letters to the daily newspaper Politika and the weekly NIN throughout the 1980s, Kosovar Albanians are described as “beastly, monstrous, and disgusting.” This narrative was not only reinforced by cultural productions like film but was also instrumental in creating a hostile environment where anti-Albanian propaganda was commonplace.

Another example of such portrayals is the 1998 film “Stršljen” (The Hornet), directed by Gorčin Stojanović. The film centers on a love story between Adrijana, a Serbian woman, and Miljaim, an Albanian man involved in criminal activities, set against the backdrop of rising tensions in Kosovo.

One scene in the film struck me in particular: Abaz, an Albanian man linked to the Albanian criminal underworld, is derogatorily called a “Šiptar” and a “son of a bitch” by the Serbian man who employs his services. The Serbian character says this jokingly but then questions why Albanians take offense to “Šiptar”, noting that Albanians refer to themselves as “Shqiptar”. This moment underscores the profound cultural disconnect and illustrates how racialized slurs against Albanians had become normalized in Serbian and wider Yugoslav society.

This film perpetuates problematic depictions of Albanians and Kosovo — a pervasive pattern in the Yugoslav film industry that, unfortunately, continues to shape portrayals in many post-Yugoslav countries today.

Frustrated by the constant portrayal of Albanians as criminals, warlords, fascist collaborators, or irredentists — or by the complete erasure of Kosovo’s history — I shifted my research towards discovering representations of Albanians and Kosovo that celebrate its beauty and its people, free from stereotypes.

Discovering talented Albanians and the beauty of Kosovo

My research was not marked solely by negativity. I discovered Albanian individuals from Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia who made significant contributions to the Yugoslav cultural scene. The impact of actors like Bekim Fehmiu cannot be overstated; he provided me with a profound sense of representation, demonstrating what Albanians can achieve in the arts when given the opportunity. My father always spoke of Fehmiu with pride, his eyes lighting up as he recounted Fehmiu’s international success. Unlike others, Fehmiu wasn’t limited to roles as a warlord or muscle-bound fighter but portrayed a range of characters, including leading roles as a heartthrob.

I also discovered a beautiful documentary produced in 1972, “Prizreni qyteti i burimeve dhe bukurisë” (Prizren, the City of Resources and Beauty), made by Zastava Film and directed by Zvonimir Saksida. It showcases Kosovo’s stunning landscapes and Prizren’s rich history from a Yugoslav socialist perspective, of course. Watching this film in my late teens, I found it incredibly affirming to see these beautiful spaces and people from Kosovo, offering a perspective that felt authentic rather than exploitative.

The documentary features intimate moments of Kosovars from various ethnicities — conversing at market stalls, walking down sunlit boulevards, and creating intricate embroidery. These scenes spoke to me intensely, and I had wished these nuanced depictions of Kosovo and its people had been more common in the Yugoslav film industry. I believe it’s essential for cultural groups to see themselves fully reflected on the big screen, to experience representations that show the full range of their stories — the good and the bad.

Growing up in London, I mostly saw Kosovo represented through narratives of war and displacement. Revisiting Yugoslav film in search of cultural representations furthered this negative portrayal, with shallow stereotypes dominating a prominent film industry in the region.

But within this history, I can see the profound growth the Kosovar film industry has made post-war and independence. Seeing films produced in Kosovo, with Kosovar actors at the center of their own stories is heartwarming. The icing on the cake is watching them achieve box office success globally, a further testament to what we can achieve and produce.

This article was originally written in English.

Arbër Qerka-Gashi is a London-based curator, researcher and writer of Kosovar heritage. Arbër writes on a range of themes but is particularly passionate about Balkan heritage, diaspora experiences, Albanian identity, and Kosovo’s cultural expression. Arbër is the founder and editor of the digital platform and annual publication “Balkanism” and co-founded the Balkan London Collective events initiative.