What is the music of your past? Is there a song you associate with a particular time of your life? Is there an everyday sound that brings out memories for you?

While in conversation about sound’s capacity to evoke memories, music usually comes to mind; this article will explore some ideas behind listening to historic sites and the capacity of soundscape to bring out memories. This is challenging, as we are not primed for such a task. From childhood days, rhymes and games attune us to listening to the natural world around us, but listening to specific sites, their human and animal inhabitants, with care and appreciation is, for most, a niche activity.

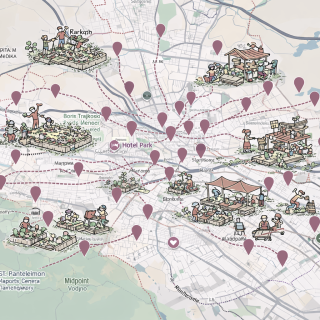

Nonetheless, over the last ten years, I’ve been dedicated to listening to urban soundscapes, in the main. I did this by recording and collecting the sounds around me, as well as listening while walking alone or in a group. Over time, this has grown my appreciation of everyday sound. In parks, I notice the hum of urban activities, chatter of people, and rhythms of footsteps, along with guttural voicing of pigeons, and the steady buzz of bumblebees near my feet.

These days, I don’t listen to music too much, and whenever I can, I tune into the continuous sounds as music around me: in my flat and neighbourhood, during my walks, and even in shopping malls.

Bringing this focused listening to sites of memories allows the past to resurface in new and interesting ways. Sound art authors such as Katherine Norman, Peter Cusack, and Salome Voegelin acknowledge the capacity of sound to evoke memories. This can take a form of a particular bird call or a storm that becomes deeply engraved on our minds and, when experienced again, transports us to the past.

However, listening to historic sites, particularly sites of personal memories or trauma, opens up a whole array of emotions and impressions, as listening requires slowing down, tuning in, and acknowledging one’s personal position in the broader context. Compared to landscape that can be enjoyed from the distance as a view in front of us, when it comes to soundscape, a listener is always at the centre of their own soundscape (Paul Rodaway, 1994, p. 86).

Hence listening at the sites of first-hand experience of conflict allows recollections, dipping into the past whilst pulling the listener back to the present simultaneously. When listening in a group, people open up and share their experiences with each other. In Sarajevo for instance, people talk about air raid sirens that they used to hear in the city and the types of ammunition they would hear in specific locations or in certain periods of the siege in 1990s. Specific events and encounters are discussed: ‘this is where I last saw him/her’; ‘we used to come here daily’, ‘I was just about to leave the house when this happened’; but listening also pulls them back into the present, through sound of the wind or someone passing by.

While at Trebević mountain, the sounds of the renovated cable cars passing above us and the joy of children playing in the distance mediates this retrieval process, creating the back-and-forth shift through time, increasing even further the listener’s appreciation of the site.

Trebević Mountain was one of Sarajevan’s favourite picnic sites before the war. The mountain is also the site of a now derelict bob sleigh, that was used for the Winter Olympics in 1984, and a cable car destroyed in the 1990s that was renovated in 2018.

Although studies of sonic properties of memory sites across the Western Balkans are scarce, sites designed for contemplation naturally welcome listening. Even those commemorating the events from the World War II evoke memories of the past, even if the actual events these sites commemorate are not within the living memory of most listeners.

At sites of Yugoslav Spomenici, I often overhear visitors reading the plaques and retelling stories. Modernist architecture, in balance with the environment, often embraces moss, grass and shrubs growing over concrete, placing it in the dialogue with the natural world. Visitors unconsciously become listeners and mediators engaging with history in a larger geographic and temporal context. Even monuments in remote locations, as masterpieces of architecture, are designed to be in communion with their surrounds. They are spaces for slowing down and tunning into one’s inner world as well as the environment. Sonically, they expose the listener to a range of natural sounds while the materials used in their construction create echo and reverb, naturally amplifying footsteps or isolated voices. These effects of architecture encourage testimonials.

Spomenici such as the Ilinden Monument in North Macedonia or Jasenovac in Croatia provide the transition from reverberant indoor spaces used for education and contemplation to the vast outdoor spaces that embrace the listener into the much broader acoustic environment. Such use of architecture utilises the potential of sound to highlight temporal transitions, enabling healing.

Maja Zećo is a contemporary artist originally from Sarajevo and now based in Scotland. She works in sound, video, and performance art. Her pieces are often site-specific and relational, negotiating personal and group narratives of identity and history. She has exhibited internationally. In 2019 Maja obtained a PhD in fine art, on sound and performance art practice, based at Gray’s School of Art (RGU) with the support of the Sonic Arts Programme at the University of Aberdeen.