September 15, 2023, felt like any other workday for a court monitor like me as I prepared to leave home to report on court proceedings. That day, however, I would learn that the past is never truly behind us. It finds ways to resurface, reshaping our understanding of history and our own stories, sparking new quests for personal and collective truth.

As I navigated the corridors of the Basic Court of Prishtina and found my way among the courtroom benches, I had a chance to take a closer look at the details of the case unfolding before me. It was then that I made a chilling discovery: the case I was reporting on for BIRN concerned events that had taken place on the exact day my family and I fled Kosovo twenty-five years earlier, in the very village we had left behind. Writing that article transported me back to my childhood — a refugee alongside my mother and brother, afraid with every step we took.

It suddenly became difficult to separate my job from the refugee within me. The indictment detailed brutalities that mirrored the fears I had unknowingly lived through as a child — killings, beatings and the inhumane treatment of civilians.

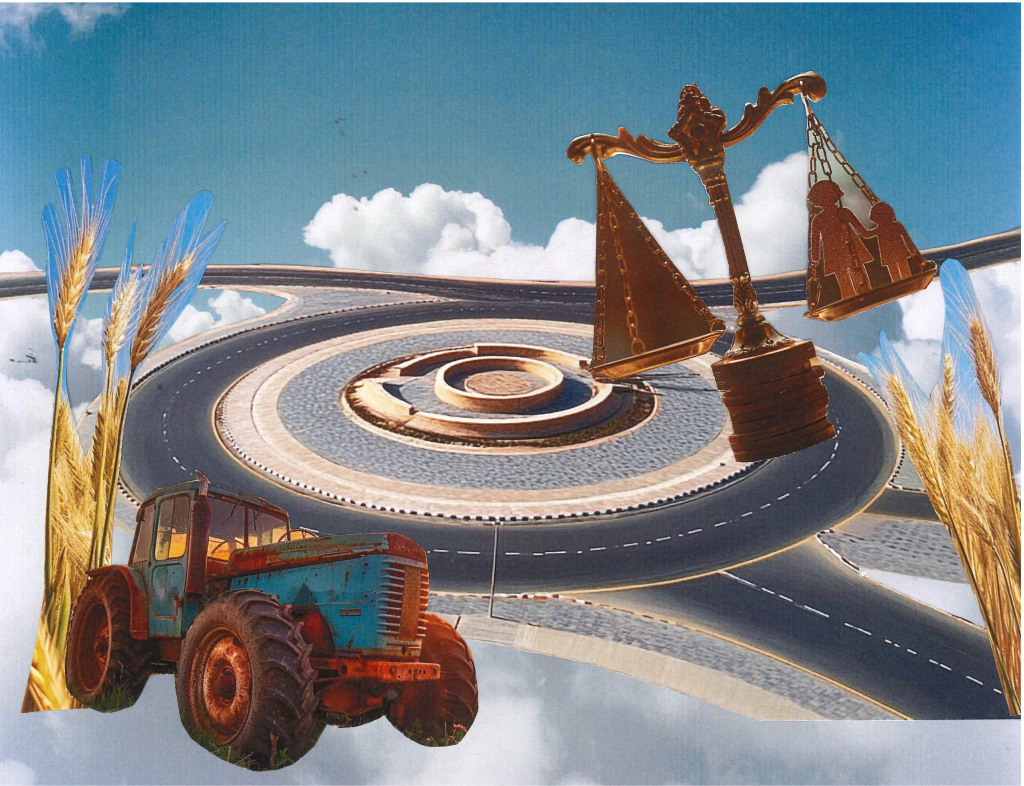

I was just four years old when we left Saradran-Istog for Tirana, crammed into a crowded tractor with other members of my mother’s family. Our belongings were hastily packed and fear clung to us like a second skin. The memory of that day is a patchwork of fragmented images drawn from both my own recollections and the stories told to me as I grew up: the chaos, the sirens, the faces of strangers, all fleeing an unimaginable terror I didn’t understand at the time but could feel all around me.

My mother often recounted the stories of our escape, which felt like an echo of a shared history. She spoke of the nights of May 7 and 8, 1999, when we gathered in a field, huddled together as fear wrapped around us like a cold blanket. While she tried to sleep beneath the stars with her two children, the shouts and movements of Serbian police jolted her awake. Those nights spent on a tractor in an open field were filled with the distant sounds of gunfire — an unsettling symphony that invaded her dreams. She often described them as the two most terrifying nights of her life.

We found safety in Tirana, forever changed by the violence we had escaped. Ours was just one difficult journey amid a broader ethnic cleansing campaign. I now realize that, as a child, I was shielded from the full weight of what that truly meant.

As we made our way through the mayhem, my mom told me about our encounters with Serbian police officers and paramilitaries who were drunk, their faces twisted with aggression as they aimed their weapons at us, demanding money with threats. I grew up listening to her stories, including how my uncle had come from Germany with ready-made passports, eager to bring us to safety. “Each day was a struggle,” she would say, recalling the six weeks we spent in Tirana with no information about my father, whom she had to leave behind in Peja with his family.

Surprisingly, my mother refused to go with my uncle to Germany, held back by the fear and uncertainty of not knowing whether my father was alive. This decision puzzled me for years, especially as I faced frustrations regarding the economic, social and political struggles of Kosovo. I would often turn to her, lamenting that if she had accepted my uncle’s offer, we could have been in Germany living a better life. She would gently remind me, “When you grow up, you’ll understand.”

Now, as I reflect on those moments, I see the profound depth of my mother’s love and sacrifice amid the chaos. It wasn’t just about safety; it was about trying to keep our family together, even when the world was falling apart. Those narratives became an integral part of my identity, shaping my understanding of loss and resilience and teaching me that survival often comes at a profound emotional cost.

When we came back to Kosovo, we found my father and his relatives alive and safe. Many others were not as lucky. Many were killed or massacred, many had family members forcibly disappeared, leaving them forever haunted by horrific crimes.

My work in the field of justice has taken me to countless court trials, but this trial felt different. It forcefully weaved my story to those of countless others affected by the war. In the following months, as the proceedings unfolded, I listened intently to the testimonies of the witnesses, each story playing out like a chapter of a tragic novel. I could see the faces of those who had lost loved ones, their eyes shimmering with tears.

Among them was an 86-year-old man, who had lost three sons and two other family members on the day under investigation by the court. Despite his immense loss and suffering, he summoned the strength to confront the accused with a heart-wrenching urgency, demanding answers to questions that had haunted him for years: “I want to know who killed my three sons. If you didn’t do it, you must know who did.”

In the midst of this anguish, it struck me that the courtroom seemed like a crossroads of both hope and sorrow — a place where the weight of history collided with the yearning for justice. It was also a site for another crossroad: the full-circle encounter between the adult me and the four-year-old me, facing a man accused of crimes committed on the day and in the place where I became a refugee. In that moment, I understood the weight of what was happening around me and unveiled a latent but deep desire within me to ensure that history is acknowledged and remembered.

The verdict came in July 2024: 12 years of imprisonment for the defendant. Scanning the faces hardly visible in the live broadcast of the proceedings, I could see disappointment prevailing in the room. The weight of those years must have felt insufficient compared to the magnitude of the tragedies that had preceded them. Yet, amid the conflicting emotions, I recognized that this verdict was also a beginning — an important acknowledgment of the wrongs that had been inflicted. It was a step, however small, marking a shift in the narrative: a public declaration that these crimes had occurred, that the victims’ stories mattered, and that our stories could continue.

In September of this year, a new indictment emerged concerning crimes committed in the Istog area, bringing to light additional individuals implicated in these atrocities. This included a specific focus on events that occurred between May 7 and 9, 1999, further interweaving the tractor where my mom, my brother and I slept with the threads of pain and loss that haunt many.

This mirroring of stories made me realize that justice is not just a legal outcome or resolution; it is an acknowledgment of pain and suffering, a crucial step toward healing for individuals and communities alike. It carries with it the weight of history — a collective sigh of relief entangled with the lingering echoes of trauma. Through storytelling and remembrance, we can honor those who suffered and continue to carry their legacies forward. In doing so, we ensure that their stories are told, their struggles recognized and their sacrifices never forgotten. And when we do forget, we should be grateful for signs from the universe that reawaken us to this truth, as I was on a seemingly inconspicuous day in September.

This story was originally written in English.

Donjeta Rexhbogaj is a law graduate with a passion for transitional justice. She has researched post-war justice in Kosovo at the University of Graz and worked in the legal office at BIRN Kosovo. Donjeta enjoys writing on human rights, reconciliation and dealing with the past.