In most Eastern European countries, the architecture of the socialism era was characterized by a rise of monuments as an admixture of nationalism and socialism. Almost every country in the socialist camp had its own “Mother”[1], proudly eternalized in bronze: from Ukraine to Georgia, to Armenia, to Russia and to Albania. These monuments depict anonymous women[2], an incarnation of the feminine/motherly features of the Motherland.

“Mother Albania”, the “Motherland Monument” in Ukraine, the “Motherland Calls” in Russia, “Mother Armenia”, and the “Mother of Georgia” – all place the woman’s figure on a pedestal. While the “mother” of a nation was often an abstract piece of bronze, the nation’s “father” was always a real person. He had truly lived. He was the “inventor”, the “hero” – leading a medieval uprising or the recent socialist revolution.

Of course, this in itself contains a portrayal of the “typical woman” and what her place in the socialist society was, determined by the dominant ideology of the regime. The woman was the mother. She was the mother of the nation. She was its physical and spiritual regenerator. She was the one who gave birth to the “brave men” and then raised them with the “spirit of patriotism”. She was in the passive role of the provider, the nurse, and the educator of younger generations. Consequently, the nation’s most extoled figure should be a woman. Monuments of the socialist “mothers” of the nation were the secular “Virgin Marys” adapted to the political and ideological circumstances of that era.

Kosovo was an exception. Kosovo did not have a “mother” made of bronze. Perhaps due to the fact that it was neither an independent state like Albania or those in the USSR, nor a republic such as Armenia, Georgia or Russia.

In fact, Kosovo not only does not have a monument of the “nation’s Mother”, but in general there is a minimal presence of monuments, memorials and busts of historical female figures. While every corner is filled with monuments of male contribution – mainly to political and military activity, but also to culture, arts, academia, etc., – the number of monuments built in honor of women is low. Extremely low.

Needless to say, without wanting to fall victim to victimization, it must be acknowledged that the number of men who have contributed to various sectors of Kosovo’s society is larger than the number of women. Nevertheless, this has its own explanation. As a society where patriarchy has been very powerful, especially in the past, the number of women with opportunities to succeed in public life, equal to men, has been much smaller.

It was difficult for a woman to engage in political or military activity. During the Kosovo war, the number of women fighting, compared to men, was proportionally less. Of the few females involved in the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), many played a supportive role, they worked as medics, were trusted messengers in the field and managed war logistics, mainly in cities. In a patriarchal society, war and combat are seen as exclusively belonging to men, and war itself is seen as a masculine feature. Given the small number of women in the KLA, compared to men, the proportion of memorials dedicated to females is much smaller.

The Monument of Mother Teresa

In fact, the first Albanian woman to whom a monument was erected in Kosovo, was neither born in nor had grown up here. She was a religious missionary. She was Mother Teresa. Born in Skopje, a city very close to Kosovo and one that parallels many elements of Kosovo society. At the age of 18, she went to , and a year later, in 1929, she left for India to serve the poor on behalf of a Catholic mission.

Mother Teresa never forgot her Albanian roots. In December 1990, she visited Tirana, then still under the communist regime. Mother Teresa met Ramiz Alia, the President of Albania and successor of Enver Hoxha, and asked him to grant her permission to open her charitable mission in Albania. She also did not forget Kosovo. In fact, during her life, Mother Teresa visited Kosovo and Skopje five times[3]: in 1970, 1978, 1980, 1982 and 1986.

With the disintegration of Yugoslavia in the late 1980s, political pluralism was also emerging. The first non-communist political party created in Kosovo was the Democratic League of Kosovo led by Dr. Ibrahim Rugova. Rugova based his public discourse on the historical references of the past and Mother Teresa was one of the most important figures of Rugova’s political narrative.

Rugova also used these figures in symbolic terms. After the war, he proposed to build a Catholic cathedral in the center of Prishtina to honor the Albanian missionary. In 2002 the location was decided: the Cathedral would be built where a secondary school was, in the centre of Prishtina. In 2007, the Government approved the building of the Cathedral “Saint Mother Teresa”; and in 2010 it was inaugurated on the 100th anniversary of her birth.

Earlier than this, however, in July 2002, a monument honoring Mother Teresa was built on the boulevard in the city center, making her the first woman to whom a memorial was raised after the war.

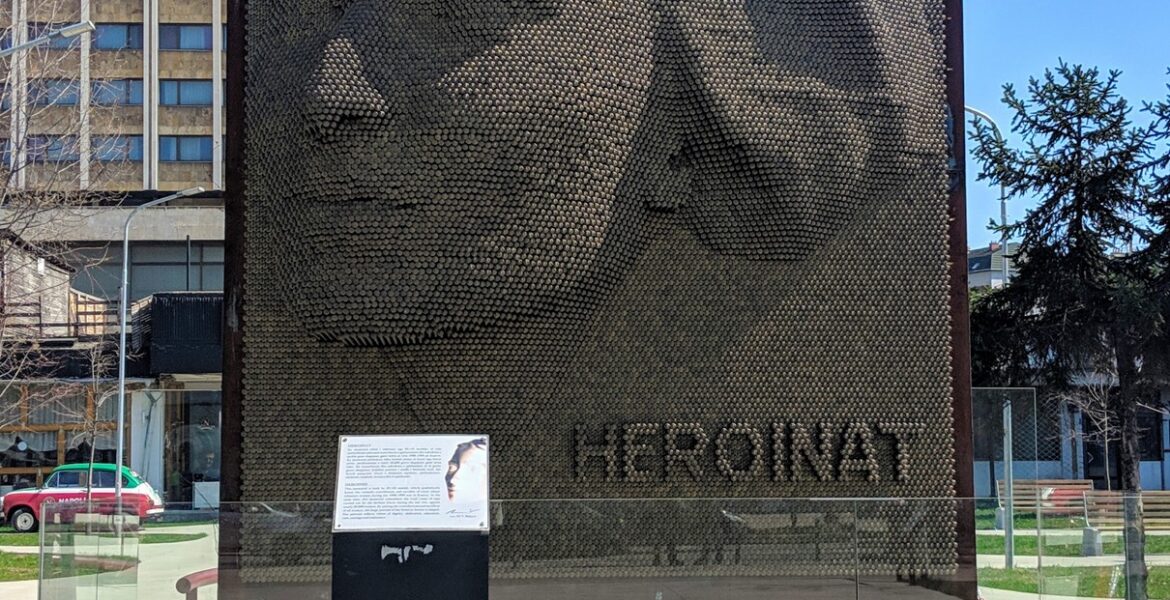

The “Heroines” Memorial

During the last war in Kosovo, in 1998 and 1999, thousands of Albanian women were raped[4] by the Serb military and police forces, as well as by the Serbian paramilitary groups linked to the Serbian government. According to some estimates[5], the number of raped women is 20,000. Individual statements by survivors are horrifying; they include accounts of rape in homes, in front of family members, in detention centers, in refugee lines and accompanied by beatings and humiliation…

To this day, little has been done for this “category” of survivors of the war. Despite the adoption of a law that foresees that these survivors will have at least material reparation and moral support, bureaucratic complications have so far neglected its full implementation. In fact, the process of listing the women who were abused during the war has stagnated to this day.

Though overdue, remembrance for these women has not been absent. In June 2015, on the 16th anniversary of the liberation of Kosovo, a monument was built in the center of Prishtina honoring the women raped in the war. It is a feminine face built from 20,000 pins, each representing a survivor of rape in Kosovo. It is not a statue or bust for only one woman, rather it represents the pain of thousands of women.

The Statue of Hyrë Emini

Hyrë Emini was born in Ferizaj in 1973. Since her student years at the University of Prishtina she was engaged in the Council for the Protection of Human Rights and in illegal organizations. At 21, she was arrested by the State Security in her hometown. After being released she went to study in Tirana, but in 1998 returned home to become a Kosovo Liberation Army fighter. Hyrë fought in difficult battles, along her fellow men warriors. Her nom de guerre was “Mira”.

After the war, Hyrë was engaged in the Kosovo Protection Corps (KPC). Meanwhile, when armed conflict broke out in Macedonia in 2001, Hyrë resigned from the KPC and became a member of the National Liberation Army (NLA) in Macedonia. On 29 July 2001, together with four of her fellow fighters – one from Kosovo, one from Albania and two from Macedonia, Hyrë was killed fighting at Kuk-Zabel, Gostivar.

In March 2017, the statue of Hyrë Emini-Mira was unveiled in the center of Ferizaj, her birthplace. Many citizens came out to honor the memory of Mira. Mira thus became the first KLA soldier in honor of whom a statue was built in Kosovo.

The Statue of Xhevë Krasniqi-Lladrovci and Fehmi Lladrovci

Xhevë Krasniqi-Lladrovci was born in 1955, in a village in Drenica. She was the daughter of an activist of clandestine organizations who, in the 1980s, worked illegally to nourish the uprising against the Socialist Yugoslavia. From a young age, just like her father, she was engaged in the resistance movement.

During her political activism, she was introduced to one of the leading activists of underground operations, Fehmi Lladrovci. Fehmi would later be arrested and sentenced to 10 years in prison, but before that, Xhevë and Fehmi decided to marry. Despite Fehmi being in prison, Xhevë lived at his home, as tradition called for, and became a bride without a groom. After Fehmi’s release from prison, both of them, due to political persecution, decided to leave Kosovo and seek political asylum in Switzerland, where they continued their political activism until the spring of 1997.

In May of that year, Xheva and Fehmi left for Kosovo, traversing the Albanian mountains for several days, and attempting to arm up to launch KLA cells in Kosovo. Their entry in Kosovo failed, due to being discovered by Serbs, and they would only make it back in March 1998.

Xhevë participated in all of Drenica’s toughest battles. On 22 September 1998, Fehmi was killed leading the fight. In order not to waver the soldiers’ confidence, Xhevë took the fighting command and continued until she was killed a few hours later. Xhevë and Fehmi were not only a married couple, but also comrades in activism and war.

After the war, Xhevë and Fehmi were declared “Heroes of Kosovo”. Xhevë was also proclaimed as “the post-mortem Major General” of the KLA.

The statue of Xhevë and Fehmi Lladrovci was inaugurated in September 2018, in the center of Drenas. As they had lived their lives, so were they memorialized – together, side by side as friends in life, activism and war.

Across Kosovo you will also encounter statues and busts of other women – such as Ganimente Tërbeshi, an anti-fascist activist who the German Nazis hanged in 1944 in the center of Gjakova. She was only 17 years old. These busts are mostly erected in the schools named after these women.

What Kosovo lacks are memorials dedicated to the female contribution to society, say, in the fields of science, academia, culture, art, or literature. It seems that, for the moment, this is not a priority for our government. A country drowning in “big topics” – from the negotiations with Serbia to the topic of the party militants’ employment – hardly can find time to discuss the topic of violence against women, let alone talk about the topic of honoring and commemorating women who contributed to our society.

We hope the future will bring a more serious commitment to women’s rights, where we pay tribute to women who deserve our respect, first to those who are alive, and then to those who have died – at least in the form of a statue.

Author: Eurisa Rukovci

Foto 1: Memoriali “Heroinat” Credits: Eurisa Rukovci, “Heroines” Memorial

[3] https://www.kultplus.com/tag/nene-tereza-viziton-kosoven/

[4] https://www.politico.eu/interactive/a-dark-legacy-the-scars-of-sexual-violence-from-the-kosovo-war/

[5] https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/aug/03/after-two-decades-the-hidden-victims-of-the-kosovo-war-are-finally-recognised