The International Criminal Tribunal is expected to hand down its final ruling in the case of Radovan Karadžić on Wednesday, March 20. The ruling will end the process that has been ongoing for almost a quarter of a century. International law experts, numerous accomplices of Karadžić and families of even more numerous victims have been waiting for the ruling for three years, given the fact that both the defence and prosecution lodged an appeal against the first-instance ruling, in which the former president of Republika Srpska and commander-in-chief of its armed forces was sentenced to 40 years in prison.

The attention of most citizens of Serbia will be absent for justified reasons: the society here, has been trapped at the very beginning under the ruins of democratic institutions, from which power is transferred to para-state centres of decision-making in an increasingly open manner. Organised crime and an almost complete control of the national media are not the only similarities with the period in which crimes, which Karadžić is accused of, were perpetrated. Hate speech and violence have again become the dominant model of public behaviour. From there, they flow over to the private lives of persons consumed with survival, fear and distrust.

The anti-government protests that have been ongoing for months are unarticulated and diffused, just as the regime that they are challenging, although the protesters have been joined by many cities throughout the country in the meantime. Patriots and traitors, Europeans and Russia lovers, anti-vaccination activists and university professors, homophobes, neoliberals, former defenders of Kosovo and future defenders of Vojvodina are together in the streets, all of them united in a single body, cranky and ugly, but one that stubbornly refuses to break down. Like creatures that manage cabinets and state authorities.

Distrust and uncertainty are ascribed to the magic interpretation of our troubles and discovery of the causes in reality shows, turbofolk music, globalisation. Any voice of reason is a potential manipulation of the ”deep state” or foreign agencies, which distracts from some truly important events. Citizens group around the perceived power, both political and social one, where the power is proven by abusing the weaker ones and where a victim is always already guilty, because he/she failed to adapt his/her behaviour on time. The public space is swamped with racism and misogyny.

Thirty years of systematic looting of the economy, state funds and public goods results in an increasingly difficult access to knowledge and ideas. A language, which expresses the values of the modern politics and society, boils down to bureaucratised terminology, which is not intuitively understandable to those, whose rights it is actually related to. The expansion of new technologies has inundated the speech with ex

In the general chaos, Serbia has been left to itself, staggering from year to year through identical cycles, hoping that this time, it would manage to breathe in the power of sabornost, the spiritual community,[1] in its two-dimensional political photomontage, so that over time the uneven junctions of the Frankenstein-like body can become even in a natural manner. The mythical consensus was actually reached in 1990s over the graves of victims of war crimes committed in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo. Our cycle of staggering could therefore be followed along the anniversaries of crimes committed in Višegrad, Štrpci, Prijedor, Vukovar, Suva Reka, Vučitrn. In Sarajevo. In Srebrenica.

The political meaning of the genocide committed in and around Srebrenica in 1995, which is the key count in the indictment against Karadžić, in today’s Serbia is still nothing else than mere manipulation of masses through tabloid fabrications about global conspiracies against Srbhood. Persecution, extermination, murders, deportations, terror of civilians and other indictment counts have been left to the oblivion – the whereabouts of the secondary mass grave of civilians killed in Kosovo, discovered at the outskirts of Belgrade, for example, or unpunished perpetrators of crimes in Croatia, who are today working at municipal administrations, or the bloody money that has been laundered through public companies and private monopolies for decades.

Impunity is what truly connects the incompatible parts of the political body of Serbia. New generations of accomplices are growing up, the network covering state institutions has been growing from year to year, from the armed forces and the police, over courts and prosecutor’s offices, to public companies, and even utility companies that transported persons to be shot by a firing squad or participated in the cover-up. They are sensitive to blackmail, which makes them ideal partners for every next violation of law, every next abuse of power, looting of public goods or beating up opponents.

War crimes implied not only political decisions and organisation, but also extensive technical and financial logistics, the traces of which remain unexplored. Trials before the International Crime Tribunal largely represent an exemption from the rule established before domestic courts, where war crimes are processed at the level of immediate perpetrators, whereas persons that ordered and organised the execution and cover-up of crimes remain beyond the reach of justice. Many of the perpetrators of crimes were frequently recruited from the underworld, and their war tasks were often financed by illicit drug and arms smuggling as part of the cross-border cooperation of the Balkans mafia clans. Once the war ended, the returned to the streets of Serbia to patrol the captured state and bring up their successors.

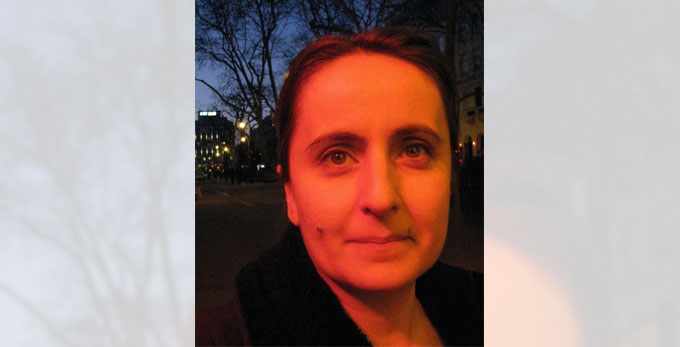

Milica Jovanović, freelance journalist from Belgrade

[1] The term sabornost (Russian: Собо́рность), meaning ”spiritual community of many jointly living people, was coined by the early Slavophiles, Ivan Kireyevsky and Aleksey Khomyakov to underline the need for cooperation between people, at the expense of individualism. (Translator’s note)