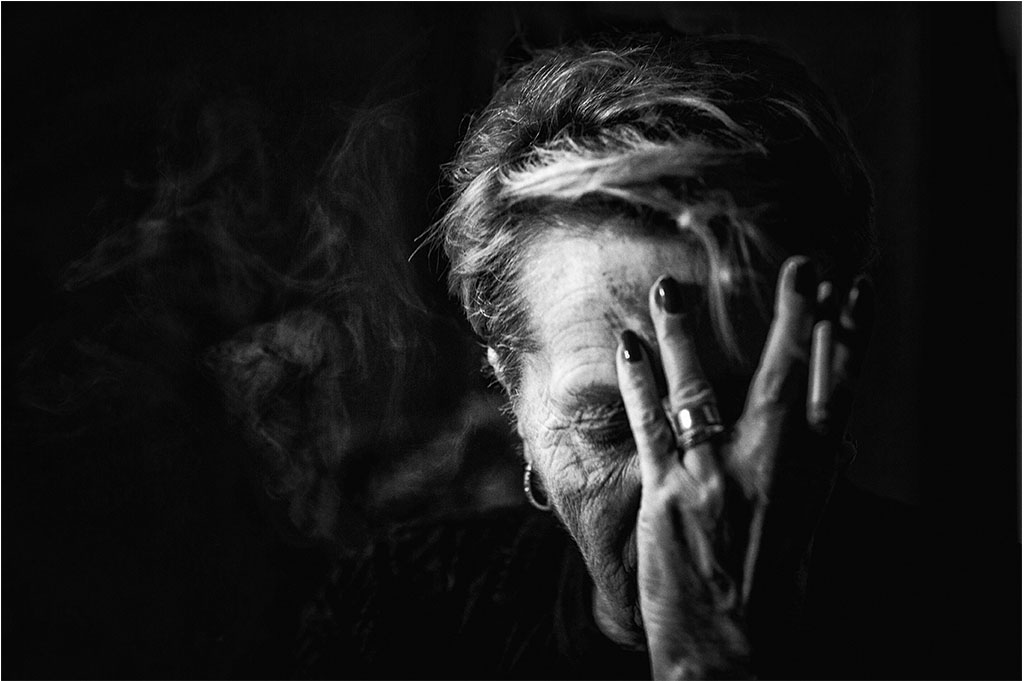

INTERVIEW WITH: OLGA STOJANOVIĆ

Marko Stojanovic was the director of a primary school in Ferizaj at the time of NATO bombing. Convinced that the war would soon be over and that the collective would return to the disrupted teaching, he thinks there is no need to distribute the work documents to the employees. With the end of the bombing and the war, Albanians are placed in that school, while many Serbs of the city are displaced in the villages around Štrpce. There they organize the teaching of the adult Serbian community of the area. Accompanied by members of Polish KFOR, on September 1999, Marko went to his former school in Ferizaj to request from the Albanian colleagues the remaining documentation of teaching in Serbian language.

His wife, Olga, is full of doubts about his disappearance. She did not trust KFOR efforts to help him, and even believes that the American colonel is somehow involved in Marko’s kidnapping.

Olga Stojanovic: Narration in first person

I was born here in Štrpce, in 1950. I was the only child of my parents. I was educated here, in the primary school in Štrpce. I can say that my parents had educated me without problems. My father was a simple worker, but his salary was enough for us. I lived in a family with the uncles, their wives, our grandfather and grandmother. It was a good and modest family. Such was life then, we all lived in a community. When time came to go to high school, my parents decided to enroll me to a teachings school, which was the only one in Ferizaj. I was enrolled in it, and since I was a single kid, my parents decided to come with me so I would not face housing problems, as I was a common village girl, with no life experience. We found a flat to rent. I lived with my father and mother while I was in school. I finished the teaching school.

During schooling, I met Marko Stojanović, my future husband. The other secondary schools lasted for 4 years, and the one I did, the teaching school, lasted for 5 years. So, I finished school sometime around 1969-70 or 1970-71, I do not remember exactly, and since I was alone, my parents had to decide to go somewhere to take me to a college or a high school. But they decided not to leave me, afraid for my future. They decided that I should try to get a job, with my high school.

At that time, I wanted to go further, because I was ambitious. The dream of my life was to complete the music school. Even today I consider it an unfulfilled dream, and certainly not only the faculty, but I would have done all the music-related education, as I would very much like to go to music school. But my parents would not let me go to Prizren, to the music school.

I finished school in Ferizaj, and after my parents decided to discontinue my schooling, I married Marko in 1970. We made our vows in Ferizaj. We did not have a wedding, because my parents were against our marriage. We found a private apartment in Ferizaj and I started my life with Marko. But that time and today cannot be compared. The law in schools was much stricter; we were not allowed to go out in the evenings after work. As for the young boys, there were many prohibited things and we only met them in a flash. Marko was from a large family, while I was a single child; he must have liked that about me. We lived in a rented place and only Marko worked. He was a teacher of the Serbo-Croatian language and at the peak of his career he won the gold medal as the best teacher in the municipality of Ferizaj and the surrounding municipalities. At first, I was at home alone. However, later I also started work. Since at that time it was difficult to find work in the city, I worked in the surrounding villages. For years I traveled. In 1971 I gave birth to our first son, Slavisa. We were still renting, life was difficult. Later, in 1975, Srdjan was born. Then, in 1978, Igor was born, also in Ferizaj. The boys attended school in there. We had a very modest life for a family of teachers. Teachers were fewer then, but since I was an only child and had my parents in Ferizaj, they helped us a lot. They took care of the kids while we were at work. I did not enroll the kids in kindergartens because my mom cared for them. This was great help because we did not pay for caretakers and we managed somehow to cover other expenses.

Marko before me had gone to town to work and understandably, tried to get a job in town for me too. I went to town, to “Tefik Çanga” school. We worked with Albanians and we went along very well with them. We had many Albanian family friends and we visited them for Eid and other holidays. Then, on the school day, March 7, we all celebrated together. Life was really beautiful, very good. We never separated. It was the 1970s. As a family, even when Yugoslavia was destroyed, we still had strong reports with the Albanians. My husband had many Albanian colleagues, whom he helped. The Albanian families were far bigger than the Serbian ones and had difficulties educating their children. At that time, my husband helped them a lot, in any way he could. Whether they had to get married or renovate their homes and so on.

The children had already grown up, Slavisa completed his high school, with very good success. However, at that time the law was such that he had to stop schooling to complete his military service. He completed his military service in Macedonia. So, due to circumstances, Slavisa completed only high school. Once he completed his military service, he started studying at the high technical school in Ferizaj. The second boy, Srdjan, finished his high school later on too. Then he decided to go to Pristina to attend computer high school.

But one day when he had just returned from Pristina, together with a friend of his, who was of the same age, and they had just descended from the bus, he crossed the railway going through the city. He was then stuck between the tracks and a train crushed him to death. It was April 5, 1997. After something like this, what can one say about life. Life became living hell for me.

The situation was already fragile, the Albanian and Serb schools were divided. Us Serbs found ourselves in a situation that we did not know how to explain what was happening, we did not know what was going on, why should, for example, Albanian children go through poisoning just because they tried to attend schools. So, there were many such bad situations. We Serbs, of course, could not do anything, because this thing was happening only to Albanian students. We could not understand what was happening, who were those Serbs who were able to do such things. Because it was logical that Serbs were poisoning Albanian children, Albanians would not do that to their own children. However, the situation was unfolding so fast that because of the consequences for the children, the teachers themselves began to not attend work. Hence, the situation was very tense. However, when we met at work, because we still held lessons in the same facilities, we all communicated with the Albanians. And there was nothing inside our collective that made the tension felt. Later it came out that the Serbian directors did their job, and then the education of the Albanians was stopped. In that period, my husband was not yet a director of the school, but a teacher in it. Later he became a director and a decision was made to divide the schools. So, the facilities were divided between Serbian students and Albanian students. It was very difficult for us who went along well with the Albanians.

In all honesty, we took the end of 1990s as a very hard blow. Serbs had begun selling their homes in Ferizaj. An Albanian colleague and friend of Marko’s, an extraordinary man, made us a proposal to sell our house to him. But my husband did not want to sell it. He said, “I do not have to sell it. No one is expelling me, no one is harming my children, I do not intend to sell, and I will stay here.” The children went out to night clubs, to nightlife, and somehow the tension could be felt in the air, but not so much. Then the tragedy with our boy happened. The schools had already stopped work, it was difficult. Marko’s’ mother was left alone in the village and we took her to live with us because she was old. When bombing began, she was experiencing the third war in her life. She was born in 1914, that is, she was 84-85 years old and it was affecting her terribly. She was ill and had had a stroke here in Ferizaj. The doctors told us that she would not make it, and advised us to send her to the village, because at that time the situation in Ferizaj was not such as to bury her there.

There was panic amongst the Serbs at school: how would we manage, what would we do, where would we go? In order to avoid panic among the school staff, Marko as a director decided not to give them their work certificates and their personal files. So, he said, “Go now, the situation will calm down and you will pick up your work certificates, and your personal files, without any problem.” We later left the school without documents, without a work certificate, without anything, because of my mother-in-law, who was ill.

Marko was not engaged in the war. He would go to school to visit the facility to see what the situation was like and return home. When my mother-in-law became very ill, we decided to come here, to their home in Beravce, a village 1 km from here, because of the mother. Igor and Slavisa remained in Ferizaj. The boy was buried in Ferizaj. In 1999, I do not remember exactly since I was sedated then most of the time, and because of the old lady we came to the village. We got nothing from home, we were convinced that we would return to our home in Ferizaj to continue with our lives.

Two weeks after we came here, my mother-in-law died. Life here was terrible. The shops were closed. We were not able to perform none of the customs that are customary at someone’s death. With many difficulties, Marko had to go to Ferizaj and only half an hour before the burial he managed to bring the coffin in which we buried his mother. Life was already becoming difficult, there was no food, no shops, nothing. Since neither I nor Marko worked, we had no salaries. We did not know then whether we would have this work in the future or not. It was terribly difficult. Then Marko decided to go to Belgrade, to the Ministry of Serbia, to implore them to allow him to open the primary school here in Zupa, so he could hire his formers staff. There were also many families and students that came here. It was easier for them to come here for school than to go to Serbia.

At that time we had convoys followed by the Polish members of NATO located here in Ferizaj. They followed people during such trips. Finally, the Ministry allowed Marko to open a primary school in Bitinje, one and a half miles from here. The school staff from our school that were found here did not have any job or documents because they were left in the school. Marko encountered many problems while trying to establish the school, hiring people here, engaging the students to attend regular classes, and because of the situation inventory was needed, but it was very difficult to secure it.

At that time, our house in Ferizaj was burned and looted, everything was taken. Then we heard that they were beginning to break the stones on the graves. That seemed the worst to me. What were we to do, where were we to go, the house was already burned, but it was not important at all. Consider the saying, “What you can build is no problem, let it go.” Our only aim at that time was keeping the stones and the grave of our son intact.

As far as work was concerned, they had difficulties accepting us in this environment, even though both my husband and I come from here. The Ministry of Serbia had decided that the employees in the schools would receive the minimum wage of 11 thousand dinars. I was assigned to Primary School “Staja Markovic”. Then the Ministry decided that we teachers would get our tasks assigned by the director according to our skill assessments, so that we would be assigned to teach art, music and physical education, and the other subjects would be taught by the teacher here from the village. But none of the directors wanted to do that. And so, we were out of work. Then Marko tried to go to High School “Jovan Cvijic” to complain, with a certification that he was the best teacher.

Slavisa got married in 1993 and had a son while another child was already in his wife’s womb. She was from Skopje. They decided to live in Skopje, sometime in 1994 or 1995. No, no, it was later. I am mixing up the years. But they are not important.

Looking at the situation created here in Zupa, we realized that it would be difficult. But from the experience of older people we knew that Zupa was never attacked by Albanians, it was never harmed. So Marko and I decided to stay here, to bring our bride and grandchildren from Skopje, here at the family house of Marko’s. But immediately afterwards we heard that the house had been burned down, and that everything was looted. For us, the house was not so important, but our boy’s grave was. He had died in 1997.

So, after the Serbian Ministry of Education allowed Marko to open a school in Zupa, he had to get the work certificates and employee files. He decided to go to Ferizaj, for work certificates and documentation, because he had left them all at school. He did not want to touch them. We were convinced that everything would remain as we were leaving it, and that the situation would calm down and in the end even if we could not return to workplaces at home, at least we would get the staff’s documents so that they could continue to live, look for work, and so on.

But then my mother-in-law died. It was a difficult time. What were we to do? Marko had been looking for a job at the high school, and we were waiting to see what would happen. Then he continued with the efforts and went to Ferizaj for the documentation of his employees. The date was September 28, 1999. So, he went to Ferizaj to retrieve the Serb employee’s documents. With him went our neighbor who was also a friend of ours, and four women. So, six people in total.

At that time the Polish KFOR was settled in Brezovica, and they agreed to take them to the school. Accompanying Marko was the professor of mathematics here, Nikolcevic. Then Svetlana Zivkovic, director of the economic school, Paun Zivkovic and two other women, I do not remember which ones. They started out here with jeeps, escorted by the Polish captain and the soldiers. On the road they agreed to go visit their homes and apartments one by one, and also the schools where they worked, in order to obtain the documentation.

Later I realized that the whole thing was organized in order to kidnap them. The only motive behind the kidnappings would be that Marko was the director of the elementary school, this Zivkovic Paun was the technical school director, while Svetlana was the director of the economic school. The directors were kidnapped because allegedly they were the ones who had driven Albanians out of work and poisoned the Albanian students. It was not exactly revenge, but something resembling it closely; what is important is that it was something.

The Polish Colonel and the army had said to them, “From the Jeep, you will get out in twos, while the others will remain in the jeep.” During the visits to all schools, this rule has been respected. But when Marko had to go to his school, he had started with the math professor, Nikolcevic, and had gone inside the school. Initially Nikolcevic had been in his apartment. So, they also visited their apartments. Then they went to the school. Everywhere they went was fine, trouble-free, without any problems. Everyone had withdrawn their documents or had explained why they had to go to the school and obtain them.

When they went to Marko’s school, the Albanians were stationed there and they were attending school, so it had already become an Albanian school. They were well received, for I have a witness; who is this neighbor, Nikolcevic, who speaks of how well they were received in the office without problems. Marko had told them that they had come for their work certificates and files, they told them they could take them without problems because they did not need them.

However, Svetlana had left the jeep in order to enter the school and started making a mess. From trustworthy sources I heard that she as a director had to be kidnapped, but that the Albanians made a deal with her, and in turn she would not be kidnapped. She is originally from Doganjevo, a village three kilometers away from Ferizaj. She then staged the story that she would like to visit her family home to see if the house was burned and asked the Polish soldiers to take her there. I do not want to talk about her any more. But Marko and Paun had remained in school with the Albanians. Nikolcević had been taken out of the school and taken by jeep to the village of this Svetlana to visit her house. When they returned to Ferizaj, Marko and Paun were no longer in the school.

What had happened? The reason given was that there were some Serbs who heard that Marko and Paun were in school and had come to get them for a coffee, but we know that no Serb was at that time in Ferizaj. Naturally, it became immediate to learn where they were, what had happened to them. We had implored all those that were there to help us understand what had happened. Time passed; after some hours the American KFOR came with a Colonel who was later responsible for Marko’s and Paun’s case, by the name of Michael Elerby, who was an American. They allegedly searched the school, searching for them, but they found nothing. The others who were in the jeep were already back home.

Then life became real hell. From the life we had as teachers – living and working in the city, regardless of everything, with many friends, Albanians, Serbs and others- we suddenly lost our son, our house, our work, we lost everything. Then I had to fight to find Marko. I was convinced that I would definitely find him, that he could not have vanished just like that, as if the earth had opened up and swallowed him. Then we began efforts with the American KFOR, namely with this colonel. Every day they would visit our house, place listening devices. The nephews, Slavisa’s children, were still very little, and were terrified when they would see ten American soldiers, heavily armed entering our house every day.

Then, I could move around in a seven-kilometer diameter. That is how much freedom of movement we had in Zupa. However, I managed to find enough information that Marko was alive, that people had talked to him, since he had taught Serbian language to Albanian children as well in the school. He was a very good teacher, he was not strict. I got information that Albanians were helping, giving food, medicines and everything else. That is what I found out. I dare not tell from whom. Not because of my safety, but because of the safety of those people who had told me these things. I got information that he was here, I went to the American colonel and told him about it, but in the end, in order not to prolong the story, it turned out that he had a duty to not find out where Marko was, but to just pretend that he was helping me. I found this out in the end.

I also found out this: Albanians, if they killed a Serb, left him where they killed him or her, so that the family could find the body and burry it, since Albanians know about our traditions. But when the Americans came, and of course they cooperated with the Albanians, it became a real hell, when they taught Albanians how to kidnap the Serbs. Why? Because the Americans had taught Albanians how to kidnap the Serbs wherever they found them and send them to the collection point assigned by the Americans. And the Albanian taught this way knew where to send the kidnapped person to a point where this person was handed over to the Americans. After that, that Albanian had no idea what happened to the kidnapped Serb. This is the real truth.

Paun, who remained with Marko, was also kidnapped. Nothing is known about him either. Same goes for Marko. They never came to get DNA samples, nor have they told us anything. Neither whether he was alive or dead. Nor that he was killed, or tortured. Nothing at all. Simply, they both disappeared. But four or five years ago, I still have the document, a French organization came here to Brezovica and handed me confirmation that Marko was killed. Then they called us somewhere between Pristina and Kosovo Polje, where KFOR is located. We went to talk, holding that letter with us, and with the announcement that it was brutal murder. There a Polish judge, a state attorney or a judge, drew me aside, since Polish army had direct responsibility in the case of Marko and Paun.

What have I not experienced with this KFOR army? There were Poles, French, Italians, Americans, I communicated with all of them. So, I was on the outskirts of Pristina there, with a woman dealing with human rights. The Human Rights Convention applies the same all over the world, right? Regardless of nationality, or whatever, the human rights anywhere in the world are the same. I kept asking things from that woman, and from this colonel, from the Italian Carabinieri, there were some Indians there too, it was terrible… I was living in very severe conditions at that time. Slavisa’s wife was already here, Igor was married. I did not know where she would give birth to her baby, I did not know what to do. Only two words I asked of them: Is Marko alive or dead? I did not want to know anything else. If he was alive, where was he, if he was dead, I had to know where his remains were. Only these two words, so that I knew what to do with the family, to make up my mind. Slavisa’s wife was on the verge of birth, I did not know where to go, and we had very poor conditions. Nobody ever told me anything. Then, I went to Klaus Reinhardt, KFOR Commander, here in a place near Pristina. There is also a document of things that I requested from him. Everything was lawful, everything. I prayed to him to help me, since I had a big family, a granddaughter, I did not know what to do, where to go. But he just got out of the seat, he was nervous, because I had gathered a lot of information, while I was with the Colonel. I immediately told him to replace that colonel, because everything was clear to him, but again, I had had many difficulties in coming to beg him to help me. But he did nothing. I told this American colonel that I would go on a hunger strike, if he did not tell me just two words: alive or dead? However, he never said anything to me.

The last day I saw Marko was when he left for Ferizaj, September 28, 1999. At that time, I used to take a handful of medication pills, because of my son who died in 1997. After two years they kidnapped my husband. So, I was alone with the pills. And life was too hard, real hell. That day he told me: “I have to go to Ferizaj because of the teachers and the staff. I was wrong that I did not distribute work certificates and files to workers. ” He also told me, “Listen Olga, I did not do anything to anyone. I hope that nothing will happen to me and that I will be back, but if I do not come back, please take care of my family.” He was in mourning for his mother, wearing black clothes, a shirt, in remembrance. His mother had died in April. In other words, he disappeared five months after his mother died.

I said, “Do not, it’s a tough time. You do not need to go.” “Nothing will happen to me – he said – do not worry.” And he went. A couple of days later, on September 29 and October 1, I told the colonel to take me to the police station in Ferizaj to call my former Albanian colleagues. There was a Pinci, the famous physical education teacher at Ekrem Çorolli, deputy director, we were friends. They would visit us for the main Serbian holidays. It was a special honor for an Albanian to come to a Serbian party, or for us to go to theirs. It was a horrible situation, I a Serb, with the American colonel, surrounded by the US military, calling Albanian colleagues to the police in Ferizaj, talking to them, to the deputy director, a really good man. I think he still lives in Ferizaj. He came and communicated with me very kindly, no matter that the times were hard and I was a Serb, and he an Albanian. He said to me: “Aunt Olga – because he is much younger than me – I’m sorry, if I knew where he was, I would not only tell you, but I would this instant go and bring him here, but my brother’s son was also kidnapped” . I asked, “What, how?” He said, “I do not know.” I said: “Why didn’t you come to us to ask for help. We would help, Marko and I, we would look for him.” His nephew was kidnapped in the period when Serbs were in Ferizaj. I said, “Why did not you come for help?” He just kept silent, without saying anything. But this Pinci, who is also in Ferizaj, when he came, he was a bit suspicious to me. He was trembling and this was noticeable. We talked, but he would not look at me at all. I said: “Please, we are friends, why won’t you look at me? You seem suspicious to me, and I don’t want to blame you for Marko’s disappearance.”

I got different information that he had not heard that Marko was kidnapped or had heard about it in the cafe. Yes, the people there were intimidated by the US military, with the American colonel next to them, and of course they did not feel well. I begged him to help me. “No, no, I cannot.” – he said. I also called a teacher, Refki Bytyqi. The American Colonel informed me that he was not there, that he had fled to Skopje after his son had been a member of the KLA and was killed.

As a spouse, Marko was extremely good. Of course, he was the head of the family, working tirelessly for the family, which was normal. Everyday life was very difficult. We had many problems. Always, like all the teachers, we had small salaries and barely managed to make ends meet, but somehow we survived. However, life was fine. He was really a great man, very wise. What I liked most about him was that he was not a nationalist, nor did he divide people into rich and poor. First and foremost, he helped everybody. He was a teacher, but he knew everything about handy work at home and house construction, he was helping people around their houses and was not ashamed to do that as a teacher and director, which he was, but he would mess up his clothes to help people. He once even organized his colleagues at the primary school “Tefik Çanga”, placed the scaffolding and they had the building façade ready with the work of only the teachers in the school. He always said that one should never be ashamed of work, because work is work, and profession is profession, it is not important whether you are a professor with a faculty, a director or anything else. Man is valued by how much he knows, how much he is involved, and how much strength and will he have to help someone.

He believed that a man should always strive, no matter what he experiences, and that he must be courageous and guide the family. His words and perseverance have helped me much in my life, in order that I do not give up. For this I miss him a lot, because of course, in years, humans forget and become more senile, but such words remain. To me it was a tremendous shock and I would not make it after my son died.

He had phoned people himself to tell them to come after we lost our boy. He was that courageous, since he too had suffered a lot as a child. They lived in a large community of peasants, who lived off agriculture alone. They did not have jobs, lived very hard, but at the time there were many dreadful situations because of the way of life, since life was not like now, with medical care, but there were times when the sick were waiting to die, only because they had no opportunity to get treatment. He had lost three brothers. When he lost his last brother, he was very frustrated, he took up to drinking, which is a vice you cannot escape from that easily. His brother tried hard to overcome the disease but did not succeed. His death touched him deeply. His brother left behind two sons, and Marko had to care for them, educate them, marry them of, prepare them for life, and now these two brother’s sons are very famous. Doctor Ilija Andrejevic in Kamenica, in the Novi Sad hospital, if I’m not mistaken. The other one lives in Kragujevac and is an economist. They are very wise people.

For a long time, I was convinced Marko was alive. Initially, I know he had taught Albanian children. They loved him dearly. He had many Albanian friends. In my soul I felt that they would help him, that they would not kill him, until I learned that there was that yellow house in Albania and that many people were taken there for internal organs. On learning this, I was slightly shaken. He was weak, not big or heavy, but still very powerful. I was convinced that he would handle everything and that he would manage with the Albanians there. No matter where, if they sent him somewhere, captured him, or whatever it was, that he would find a common language with them as he was wise, very skilled, persistent in reaching his goals, and in preserving himself. Somewhere in the dungeon, in jail, he would volunteer to work, to save himself because he knew in what situation he had left the family. First, we lost our son, we lost the house, which was later burned. When he had gone to the cemetery and saw that the stone on his son’s grave had not been touched, he said, “I do not care about the house, I do not care about anything, since the most important thing is that the stone is intact.”

For a long time, I hoped that he was alive. Igor worked in Bondsteel, spoke English, and had contact with American soldiers. They told him, “Do not be nervous, what if your dad was sent somewhere outside and is working, but he has to sign that for 10, 15, and 20 years he is not alive to his family, but is working somewhere and might be back “. But when they brought me this confirmation to sign, that it was a cruel murder, plus when I received information about the yellow house, though he was a bit older, born in 1946, and kidnapped in 1999. So, he was 53 years old. So, whether he was suitable for organs or not, I do not know. I’m convinced that they did not kill him, but that he was sent there. I have information that he was in Albania, in Kukës. Everything that I have thought of, I have achieved. Except … I was planning to go to Kukës, but I was not able to go. Because, Albanian friends would help me, but I did not know the language to cross the border and so I did not go.

I do not have any help from the Government of Serbia. I was here for six years without a job. I did not have the means to feed the family. I even have a much smaller pension because these six years I have not worked. That was the only help they gave us. I failed to gain Marko’s pension from Serbia too. I only have my pension from the Kosovo government of 130 Euro. I never got any help for the house, nothing ever.

I have already given up trying to find him. Otherwise, I’ve always been engaged and attended every meeting. One year in Gracanica when we held the meeting, I proposed to establish an association of Albanians and Serbs, because mothers, fathers, brothers and sisters mourn alike. The lament is the same. There are no Albanians or Serbs. Let’s get together. Let’s work together in looking for our people. If Albanians come to understand that the Serbs killed their relatives and learned where they were buried, I would go to the Serbian authorities to cooperate, to help them. But then they did not want to hear about it, they all laughed. It was terrible, what a disgusting approach they had.

I was in Pristina, at the meeting organized by the OSCE with the Serbian and Albanian family organizations. The Serbian organizer was an old man. When I saw that rally, I was amazed that we were together. What happened, happened, what were we to do? Neither you nor I, and maybe no one we know was involved in this. But let’s move on. It’s the nineteenth year for me without Marko and I have no word, I have no connection, I know nothing. Furthermore, my life is hell. Out of three boys, I now live alone at home. I am worried about both their families, for myself. One son was forced to leave.

The experience of my life, and I guarantee that there are such Albanian families, is that we forget everything. Will we learn where our people are, the ones who disappeared? Will we be able to achieve the basic conditions for living, work, education, healing, all of it? It is up to us. It seems to me that the government cannot stop here, and if the people so wish, the government is irrelevant. I would be happier if the relations in Kosovo were to go back to normal.

The territory of Kosovo, the territory of Serbia, the territory of Albania, the territory of Montenegro, are territories that may exist. Whose are they? It’s land. It’s real estate. Life is important, human life, mind, children, family, and home. Territories are not at all important. Will I live here in Štrpce, or will we live in Pristina, what difference does it make? It is important for you and me to exist. Will you be above or below me that does not matter. If you are honest, righteous, it does not matter if you are Albanian and I am Serbian. I think this needs to be achieved. I do not like it when people are stubborn. I do not want to name people, but stubbornness in life can only lead to bad things. Nothing else. Here is what is important.

It was a difficult time in Kosovo, it still is. And I see this clearly because I have three boys and I am left alone. I have two grandchildren who are eager to work. Igor, the youngest, has been in Afghanistan. He worked, made money, bought wood processing machines worth two hundred thousand. He bought the house where he wanted to open the factory, to work there with his big brother and other cousins. Maybe it’s not human, it’s not good for me because I’m older, I know the value of the words I’m going to say, but unfortunately, this is the truth: the mayor, the present one in Štrpce, hindered everything. He did not allow him to sign a contract with any organization. Not one. However, they wanted to produce icons, to produce whatever was ordered. But they hindered him. We did not vote for him. We were not for him, since because of him my boys had to leave Zupa in search of bread.

So, this is my life, troubled, quite hard. When I go back to the past, there are good years, but … If I were able to have my boys here to work, care for their families, and live here, I would be delighted. It is difficult, even impossible now, but it is my desire. I also want to meet an Albanian colleague and talk to her. Maybe, if anyone who hears this will blame me, but someone is bound to understand me.

I wish everything would be forgotten, even my husband. These are human fates; it was a period of life. I would like to learn from both my Serbian and the Albanian governments where the bones of the deceased are so to bury them according to customs. Their graves should be known. He might have died from a stroke or a heart attack, which would mean that he did not die by a bullet. I would have remained alone all the same and I would have to look after the family, in any case. But I might find it easier to know that he died a natural death. Maybe I would go with the children to Serbia, why should we stay here? I could not find a job. For six years I was not able to find a job, they barely accepted my 29 years of work experience, I almost remained without a pension, which is more like charity that I receive, and which is barely enough for my medicines, nothing more. Let alone enough to care for my grandsons, who are already grown-ups, and want to go out with friends, and I am not able to give them anything.

I do not blame anyone, I have no one to blame, because he was hard headed. If he would not go to Ferizaj, this would not have happened. But he believed in people, he said, “What can they do to me, I have not done anything wrong to anyone.” It was such a time, he is now gone, that was his kismet. What now? Why do my boys have to go to the end of the world because of this, why? Here is where we lived, here in Ferizaj. Here is Pristina, Gjilan, we are all here. Why? He had bought the machinery, the house, had built the factory, but still, he had to leave and let me suffer here.

I have so many experiences that I sometimes regret not having written them down. I would have published a book. What I have experienced with the colonel, where I went, what I did, it is a sin I did not write all that down. But I am so burdened now, tired of life, I so much want to forget a few things. Why should I remember these? There are moments that send me back; I cannot move forward because of them. The boy’s grave is in Ferizaj. I do not want to move his remains here, nor to Serbia. I expect my children to work somewhere, either here or in Serbia. And they are scattered throughout the world. What to do with the boy’s remains? Where should I move them to?

This is my destiny, my life, and I would not want to let the children suffer because of it. Let them advance, so that in the last days of my life I could fight for them and help them in order to ease their lives, to make them easier. Whether I will be able to, I do not know, because I do not have a big pension. I do not have anything special to do even though I’m old. I would work so that they did not have to leave. Unfortunately, there is nothing to do. Life is such. I have no one who could resolve my issues. Nobody to ask whether what I am doing is right, or whether I am wrong. But it’s not important, I move on.

My message to all Albanians and all Serbs is not to use lies, because this suffering must end. If I lost my husband, ad another woman lost her son, I know what pain she feels. Simply, let them return their remains to us. I will not react at all, I will not say anything, nor will I complain. But really, I also ask for help from my government and from the Albanian government. Let’s close this suffering and have no deceptions. I have information that over 400 mortal remains are held in sacks by an entity in Pristina. Why do I have to suffer this much and for this long, if the bones are in Pristina already? We do not want to be lied to.

Marko had a tattoo of a rifle in his left hand, from the army days. Military service was mandatory in his time. On the form I had not listed this, to be sure, since I had heard people were being given – it is painful, but I must be honest – the bones of the animals, and the case was ‘resolved’. In order to be convinced that I would take my husband’s bones, I did not tell them the fact that he had a tattoo in his left hand, which Marko told me runs all the way to his bones. I thought it was possible to see that rifle in his bones and then I would accept his remains.

Hence, I implore the Serbian and Albanian governments to help us, and not hide things from us, they have no reason to. I am without my husband for 19 years. A mother suffers for her son. She wants to know once and for all where his grave is. Be it an Albanian or a Serbian mother. There is no difference at all. People are people. But I really want somebody’s help to try and solve this problem. The gap between us, Albanians and Serbs, is our missing family members and relatives. Let’s do it once and for all. There is no other way.

(This story is part of “Living with memories of the missing: Memory book with stories of family members of the missing from the last war in Kosovo”, implemented by forumZFD program in Kosovo and Integra, in cooperation with Missing Persons Resource Centre, with the support of Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), Rockefeller Brothers and Swiss Embassy in Kosovo)