The history of museums, from their creation until today, testifies to how museums are regularly involved in the process of forming national identities and their constant reconstruction. International relations and conflicts between different communities and within them are usually completely masked. The goal is to create an ideal image of us – that is – of the society we live in, and not its becoming a problem or the aspiration to make real, non-museum life better. That is why museums often leave the impression of “passive/dead and elitist institutions that try to take us back to somewhere we’ve never actually been” (Gavrilović 2009). Talking about the connection between nationalism and the Museum of African Art – the collection of Veda and Dr. Zdravko Pečar in Belgrade (Museum of African Art) may seem strange at first, but a look from the inside, at those visible and invisible histories and testimonies, actually indicates that even this seemingly “foreign, distant, and unknown” museum can take us exactly where we used to be, in different time periods, including the one that concerns wars and conflicts during the 1990s.

Ever since its opening in 1977 this museum has actively tackled the challenge of implementing anti-colonial thinking and work, thanks to the founding collection created by Veda Zagorac and Zdravko Pečar. Opened as a friendly museum, with an emphasis on the fair acquisition of the objects exhibited in it (Epštajn 2021), and their character as a gift “to the distant and friendly Yugoslavia”, as well as due to the entire history of bequeathing and donating objects spanning 45 years, the Museum of African Art strives to realize the potential of a self-reflexive, anti-colonial museum sensitive to the problems of the present, in accordance with the contemporary moment. Sometimes, it succeeds in this by focusing precisely on the issues of modern migrations, the presence or absence of the African online world, on exposing inequality, the importance of remembering anti-colonialism, solidarity and non-alignment, and on the criticism of the stereotypical image of Africa and the people who live there, the omnipresent racism and discrimination. And yet, sometimes that same museum fails to realize the mentioned potentials, and remains motionless and frozen in the image of an Africa created in these areas almost half a century ago.

In that case, it is a museum that can notice and generally recognize any nation only when it manages to move away from the repetitive, petrified, and now boring images of the African continent as a monolith, or the typical symbols that accompany that image. Or, in other words, when it actively remembers the reasons for its origin first of all: the time of the Non-Aligned Movement, the active role of SFRY in its politics, and then the significance and meaning of the history of the anti-colonial struggle (Radonjić 2020). For a museum that seeks to make real, present-day life better in the here and in the now, it certainly does not suffice to merely engage in active remembering and extracting from passive memory caches and then recognizing that actual nations and people live in the “object” called Africa, preserved in the Museum of African Art; that these are nations and people we connected with, who lived and continue to live there.

In addition to the efforts to remember basic social values after surviving the nineties; to recognize the importance of anti-colonialism, solidarity, equality, and anti-racism, and to extract them from dusty museum boxes (Epštajn, Sladojević 2017), and highlight them as our significant and important heritage worth preserving, it is also necessary to draw attention to the fact that it is not an unquestionable, untouchable heritage, and that it is subject to criticism (Sladojević 2022). Simply put, it is important to point out and uncover that what is exhibited at the Museum of African Art is in collision with what is known and remembered about it.

Thanks to the dominant trend of forgetting and remaining on the margins, the Museum of African Art survived the 1990s. The significance of its heritage has been actively explored over the previous two decades. Its exceptionalism – and the and Yugoslav one too – were critically re-examined through a whole series of exhibitions and publications by various authors, including the currently open Anti-colonial Museum exhibition.

*

Apart from the fact that the documentary material stored by this museum can offer a glimpse into the history of African/non-aligned nationalisms and their collapse, which occurred, among other things, due to the emergence of the so-called national bourgeoisie, the history of the architecture of this museum also remembers the episode of nationalist conflicts in the public space and the daily press during the breakup of Yugoslavia, which obviously did not bypass this supposedly “unimportant and uninteresting” museum. Through one piece of the museum’s architecture – its dome – a broader picture of social-political systems and their changes, the breakup of the SFRY, the ideas of non-alignment and solidarity whose contours were being lost, both inside and outside the country, struggled and culminated. The publication archives and documentation of the Museum of African Art from the time of the construction of the dome (1989) and the entire following decade offer insight into the sequence of events that I will call a memory drama. Drama is a regular procedure in literary storytelling, and it is also present in mythology, the Bible, as well as in the collective memory (Kuljić 2012). I will show how the dome of the Museum of African Art functions as a memory machine (Pint 2013) through the structure of a play, that is through one possible prologue, plot, culmination, reversal, and denouement.

*

*Prologue: as one of only a few museum buildings in Belgrade, the Museum of African Art was opened on 23 May 1977 by adapting and upgrading the former art studio (Moša Pijade, Zora Petrović, Boško Karanović). It was called a “wonderful museum building”, “free-grown”, deliberately “non-monumental”, one that invites not only diplomats, teachers and students – “obligatory museum visitors” – but also “ordinary” people. It is remembered as an unobtrusive building, not only towards society, but also towards history and nature. Its architect Slobodan Ilić carefully and respectfully incorporated the space of the studio (1952) into the new building, preserving the spatial structure, the old fireplace, the bench, the builders’ signature, and from rich gardens and greenery, he removed, as noted in the project, only two trees to build this extremely low, concrete building with a flat roof, with a natural lighting system, lanterns, concrete cylinders, and a rooftop meadow. In other words, as a building aware of the importance of preserving the cultural and natural environment, as an example of architecture that gladly accepts what history and nature bequeath to it.

Plot: Not long after, that wonderful museum building began to leak. Solidarity is tested again, wrote the newspapers. In 1989, Belgrade hosted the 9th Non-Aligned Summit. Oral histories also remember the proposal to hold that summit at the Museum of African Art and its new space under the dome. However, that did not happen – the planned construction started too late, and the fact that even today, in 2022, this space is under construction is a testimony to the memory drama that followed.

Culmination: The summit passed, with or without the Museum of African Art, in the spirit of extinguishing optimism regarding the politics of non-alignment, and open distrust in the further life of brotherhood and unity. The Museum of African Art was left with the wooden scaffolding, the skeleton of the roof to deal with moisture remediation and the generally poor condition of the building. On the battlefield of the imaginary life of the dome of the Museum of African Art, particularly from 1992 to the end of 1994, individual destinies, desires, and interests clashed. For Zdravko Pečar, one of the founders of the Museum of African Art, the museum was a “victim of predatory looting in a collapsing social system”, and the dome was given the function of a synecdoche in the public debate, referring to “an insidious type of sale of social property, the process of dying out, the need for the Museum of African Art to enter the balance sheet in the division between FR of Yugoslavia and Croatia, while Belgrade is marked as a city that destroys and degrades Muslim art.” (see more: Knežević 2021). The paradox of the nationalist tone, which was attributed to both an unpleasant and dishonourable political connotation, took on geographically wider dimensions with an article published in Jean Afrique, to which UNESCO also responded. In architecture as a machinery of memory, this conflict sets in motion that Proustian mèmoire involontaire embodied in the newspaper headline about (still) the African roof of (new) Croatian wood in Belgrade, and the collapse of the Yugoslav federation, it was believed, directly led to the endangerment of this collection.

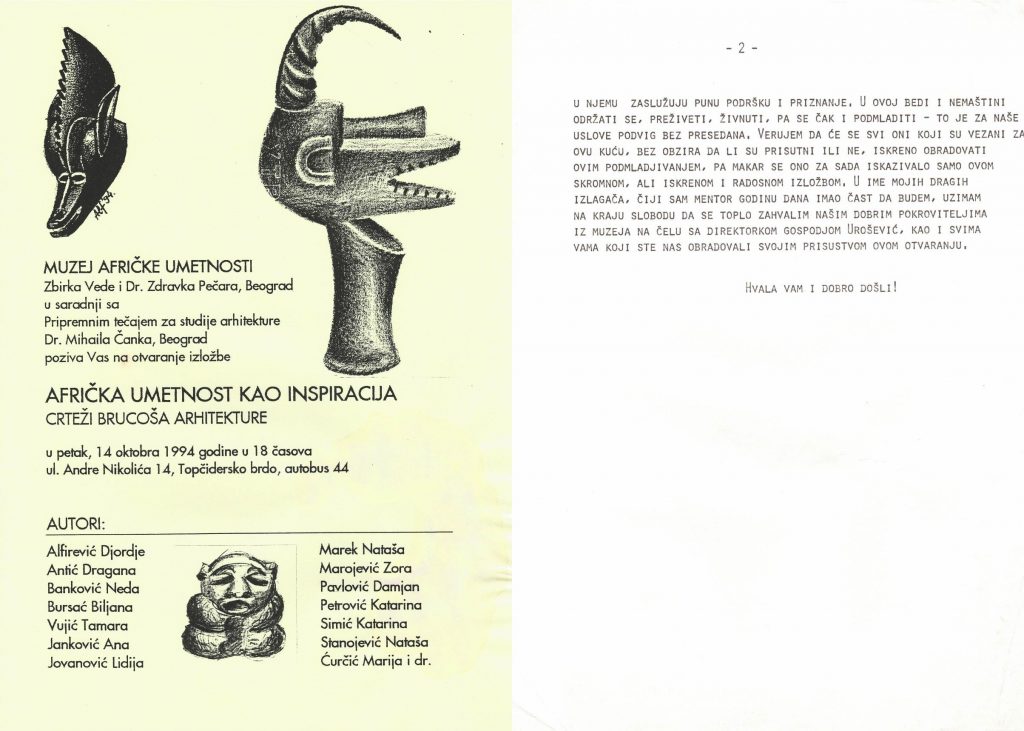

Reversal: in this misery and poverty to hold on, survive, revive, and even rejuvenate – that is an unprecedented feat in our circumstances, wrote prof. Dr. Mihailo Čanak in May 1994, when a large group of high school graduates sneaked into the attic of the building in order to prepare for the entrance exam at the Faculty of Architecture.

Denouement: to the rhythm of dance music and the art world. The early 2000s mark the role of this space in the scenography of educational, but also entertainment, music shows and videos. The fact that it is an impressive interior has certainly been proven by the artists’ frequent fascination with it and a whole set of installations, performances, and artworks that have been (and still are) inspired by it and/or in it.

*

Epilogue: an open-ended story. It is 2022 and the Museum of African Art is waiting for a building permit and reconstruction. In the process, it is predicted that the mentioned space beneath the dome, as well as the whole building that still vividly remembers the old art studio from 1952, the adaptation sensitive to nature and history from 1977, and the architectural machinery of memory presented here from 1989 to the present, will get a new form and design. With the settling of architectural layers for more than half a century, the current museum building can rightly be understood as an important place of memory, and its African roof made of Croatian wood is an episode that clearly shows how the history of the disintegration of the SFRY and its internal conflicts can be understood, seen and written just through a piece of architecture of an “African museum” on the side-lines.

What is left to the readers (that is, all of us) to consider in the open ending, is a discussion about how to understand, preserve, and use these conflicts for the sake of a better, non-museum, real life in the future. How to understand pictures in which the same space is also a shelter, a corner to escape from reality into which we slip unnoticed, a place where one can barely come alive in poverty, and on the other hand, a piece of predatory robbery and dishonourable political connotations? How to put images created through grassroots, spontaneous, and sincere efforts in the foreground, compared to those planned and formed in the ranks of the political and media establishment? For a new, truly anti-colonial museum whose realization is planned, it will certainly be of great importance to uncover all the lives of the building mentioned here. Unlike the old, representative and unchanging museum image, this one, which is able to carefully read the history of the creation of the museum, its history, as well as the architecture and heritage associated with it, will instead of a “corner, oasis or escape” to somewhere we have never been, or what after all – does not exist, be able to offer a space for discussion about, dealing with and understanding the times and problems we live in, both in the museum and, more importantly – outside its walls, whether those of ivory or of concrete.

Reading recommendations:

Epštajn, Emilia, Sladojević, Ana (eds.) 2017. Nyimpa kor ndzizi – One Man, No Chop: (Re)conceptualization of the Museum of African Art – the Veda and Dr. Zdravko Pečar Collection. Belgrade: Museum of African Art.

Epštajn, Emilia, 2021, “STORIES OF AUTHENTICITY. The origin of objects in the Museum of African Art and how the Pečar collection was created”, habilitation thesis, e-publication available at mau.rs

Gavrilović, Ljiljana, 2009, About politics, identities and other museum stories, Belgrade: Ethnographic Institute SANU

Knezević, Ana, “Imaginary and real life of one space: the dome of the Museum of African Art in Belgrade”, Social History Yearbook no. 2 (2021), 43-64.

Kuljic, Todor, 2012, Memory culture, Belgrade: Čigoja štampa

Kris Pint, “If These Walls Could Walk: Architecture as Deformative Scenography of the Past” in Performing Memory and Art in Popular Culture. ed. Liedeke Plate and Anneke Smelik (New York: Routledge, 2013)

Radonjić, Nemanja, 2020, Image of Africa in Yugoslavia (1945-1991), doctoral dissertation, Department of History, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Belgrade.

Sladojevic, Ana, 2022, An Anticolonial Museum, Belgrade: Museum of African Art.

Ana Knežević (1993), PhD candidate in museology and heritology at the Faculty of Philosophy in Belgrade, since 2016 she has been engaged as a curator and external associate at the Museum of African Art. She was part of the curatorial teams of the following exhibitions: Unprotected witness no. 1: Aphrodisiac (2019), Reflekt – Namibia 30 years after liberation (2020), Unprotected Witness no. 2: MMM (2020), The Non-Aligned World (2021), “This is not war” – liberation of spirit and land, in ink and in action (2021), Reflect #2 – fragments, fragility, memories (2022). She is currently an expert collaborator on the Reconceptualization project of the Museum of African Art. She is the author and editor of the online heritage map (https://nesvrstani.rs/), and part of the site’s editorial team (https://um.edu.rs/html/). She is in the process of working on her doctoral thesis at the Seminar for Museology and Heritology, in which she is researching the problem of cultural memory in cyberspace through internet memes as a case study, and she is interested, in addition to inevitable humor, in oral history, problems of digital humanities, culture of memory, media studies, film studies and architecture.