Rexhep Maloku

“The poisonings envenomed my life,” says Arta M. “I guess the main reason why I cannot become a mother is related to the poisonings.”

She is only one of seven thousand students who were poisoned with the nerve agent in the spring of 1990, says historian Ilir Bytyçi, elaborating on the numerous political developments before the poisonings. On 23 March 1989 Kosovo was stripped of its autonomy. The regime of Slobodan Milošević was not backing off despite various manifestations of dissatisfaction from the Albanians. The noose was being tightened around Kosovo’s neck.

“The violence and repressive measures were increasing by the day, seeping into all pores of life,” states Bytyçi. “This time, the ethnic cleansing wave would take on larger dimensions, as was the case of spring 1990 when the Serbian state, headed by the butcher of the Balkans – Slobodan Milošević – would commit a macabre act by poisoning seven thousand students, from pre-schoolers all the way to university students.”

Arta M, then a high school student in Ferizaj, did not believe that the Serbian regime would target the Albanian children. Not even the elementary school ones, as happened on 6 April 1990 with the students of “Gjon Serreçi” school in Ferizaj. Her friends from one of the fifth grades in the biggest secondary school not just in the city but in Kosovo too were falling on the ground, one by one. Some would be paralyzed, and some others would faint. It was one of the darkest days in the lives of Afërdita, Avni, Nebahate, Bekim, Sabere, Sinavere, Arben, Bukurie, Teuta, Fiza, Xhyla and Arbenita, describe historian Ramadani and doctor Agim Bytyçi in their book “Health Situation in Ferizaj and Its Surroundings in Century XX”. Students testified that the poisoning had occurred only in the annex where Albanian students went to segregated classrooms from the Serbs. The authors bring the lists with the names and surnames of all Ferizaj students who were poisoned.

The Spring of the Great Change

“Undoubtedly, 1990 was the year of great changes in Kosovo. Events that were taking place one after the other at a staggering speed were fatal for the Albanian population in Kosovo, especially for the Albanian education. Spring of that year was even more dreadful because the Albanian students were poisoned, mainly in elementary and secondary schools in Kosovo,” write Ramadani and Bytyçi, the latter being the doctor who treated the poisoned students. “There were poisonings in Ferizaj too. It was a violence never seen or heard before. What happened was something that the mind and imagination of man could never think of. So, that was the ‘mysterious poisoning’ of Albanian students,” he says.

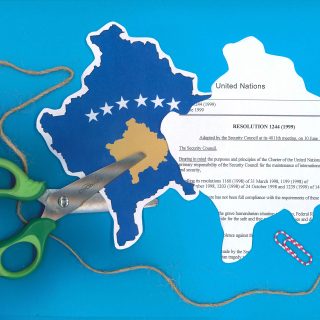

The authors qualified the use of chemical weapons against Albanian students an act of genocide, crime, and terror by the Serbian state. “This act was not an attempted act of genocide against only Albanians in Kosovo but also an act against humanity, against the principles stipulated and adopted by the United Nations Organizations,” they write.

The historian Ilir Bytyçi says that the British major David Craig would speak out about the poisoning of the Albanian students, who stated that “the children of Kosovo was poisoned with sarin poison” and that “what matters is that this poison was produced in the Potoci factory nearby Mostar.” The Bytyçi quotes the British historian Noel Malcolm, author of the book “Kosovo: A Short History”, who wrote: “These students were poisoned with the chemical substance known as sarin, a chemical weapon.”

“The poisons used against the Albanian children caused nervous shock to them,” states Bytyçi.

Arta M. would continue to suffer unexpected attacks causing paralysis and fainting. No medication could be found in Kosovo, where the regime of Milošević would make treatment difficult, as is seen by the testimonies of the students and doctors in the book “The Health Situation…..” The same book informs that students whose state was more serious would be sent through their family relations to hospitals in capital cities of former Yugoslav republics and the West. Arta M.’s family sent her to Germany.

“I stayed for two months with the family of a cousin in Germany, where a doctor treated me using bioenergy,” she says. She no longer experienced health troubles but strongly believes that because of the poisoning she cannot become a mother. “I have spent tens of thousands of euros for doctors who told me that neither me, nor my husband have any health issues but it has been almost ten years that we are spending money with no success.”

“Theatricality of Albanians!”

Doctor Shyqeri Hyseni writes in the book that this was one of the goals of poisonings by the Serbian regime. “Since then, I think that the purpose of the poisonings was not only to cause suffering to the students, and sadness to their parents, teachers and the entire population. No, they were meant to let Albanians know that this would happen to their children all the time, adding to that the propaganda feeding our worry that the toxins would affect fertility,” writes Hyseni, one of the doctors who would treat the poisoned children.

The first cases in Ferizaj were treated on 22 March 1990. They were students at the elementary school located in front of the city’s outpatient clinic. Doctors Abaz Beqa and Minire Reçica were getting ready to begin the afternoon shift at the school’s ward within the central outpatient clinic. It was 13:00hrs. Reçica had just put on the white coat and was arranging the tools on her work desk when she heard the cries for help from two young men carrying a girl. She first thought the elementary school student might have sustained injuries at the physical education hall.

“Once we laid her down on the bed, without having time to do a proper examination, the second patient arrived, which took us by surprise as she had the same symptoms as the first patient,” writes Reçica, describing the reddened marks, the muscular stiffness and difficulty breathing. “We were barely done when another patient arrived, a boy from the same class.”

Soon after, the doctors would face tens of similar cases, alarming the citizens. “There are no words, no recordings to describe the disturbance. Only those who experience it can tell. All whitecoats gave their maximum efforts,” writes Beqa in “The Health Situation in Ferizaj and Surroundings in Century XX”.

Agim Bytyçi speaks about the organization of the professional work and about his involvement in arranging for the taxis to send the patients whose state was more serious to Prishtina.

The correspondent of the Belgrade TV station for Kosovo Goran Milić stated during the main evening news on 22 March 1990 for TV Belgrade that “event the actors in Cannes would envy the acting skills of Albanians.” Infectious disease physician Stefan Balošević who had signed the report of the consortium of doctors on the poisoning, appeared at the same evening news yet speaking totally different words: “This is about a well-rehearsed theatricality.”

“As they were walking, children would hit the ground”

The situation on the field was very different. Shefki Hajdari, a resident of Nerodime e Poshtme village would twice send to the outpatient clinic children who were fainting on the streets as they were walking home back from school. “As they were walking, children would hit the ground,” he points out.

The local Serbian authorities saw to it that citizens had as little information as possible about what was happening to their children at schools. “Strangely”, as Ramadani and Bytyçi write, the antenna of Radio Ferizaj suffered accidental damages by a transportation vehicle and “therefore the broadcast of the regular program was terminated thus making it impossible to inform citizens in time.”

However, the dark news was spreading fast. The Catholic Church of Ferizaj opened its doors and transformed into an improvised hospital. The Serbian police had ordered the medical personnel to leave the religious temple and patients had been discharged home to continue treatment there, writes doctor Hajdin Ymeri, part of the medical team at the church. “The Serbian police inspectors interrogated publicly Dom Lush Gjergji, as to why he had opened the premises of the Catholic church to treat the poisoned Albanian students,” he recalls, saying that over eight hundred students poisoned during March, April, May and June 1990 had been treated in the city.

Bytyçi, the historian, says the events of spring 1990 are deeply imprinted upon the students who suffered the consequences of that “macabre cycle” orchestrated by Belgrade to strike the Albanian youth. “Even nowadays, when Kosovo and Serbia are involved in the long-term dialogue process on many issues related to the political processes of the past, the matter of poisonings has never been dealt with in a meritorious way and it is very natural that this matter take more attention so as to not forget the horrors that hit and damaged the youth of Kosovo,” he says.

Arta M. still believes that one day she will be a mother. Her hope is kept alive by a relative of hers, also poisoned, who after many attempts, had a child.

The Testimony of “Medecens du Monde”

The historian Ilir Bytyçi quotes the testimony of Dr. Bernard Benedetti, a psychiatrist, a world-famed doctor, member of the association “Medecens du Monde” and founder of the University of Corsica. He quotes Benedetti, who had been mistreated while conducting his field work: "Mostly the police were hindering us. They were present at every step of the way slowing down our work. The police would follow the doctors everywhere and the worse was when the police would chase the Albanian population. That is why I have written, I have spoken and will continue to write and speak because it is unacceptable when civilian police officers enter the consultation rooms and order the doctors to cure the sick ones!” – reads Bytyçi the quote from Benedetti. “I experienced first-hand their arrogance. They even took my passport away three times! The key obligation of a doctor is to cure and save people’s lives, speaking unimpeded with them. In fact, this is one of the key values of democracy. First of all, democracy means to live but to live, one must have the opportunity to be cured, so to be cured freely by a free doctor, which was not possible in Kosovo. The presence of the police at the hospitals is unbearable pressure,

just as the presence of armoured vehicles with police around the city streets.”

© KOHA Ditore

(This article is published in collaboration with forumZFD Kosovo, as part of the activity “Dealing with the Past”)