The politics of memorialization and commemoration in Kosovo have been shaped by the war of 1998-1999, which has organized them around the idea of the heroic as the most sublime truth. The sublime truth is also the only truth of the Kosovo war. The heroic has served as the organizing principle of all other forms of narrating, public discourses, political organization, gaining and maintaining power, of the organization of the social, economic, media, cultural, and educational life.

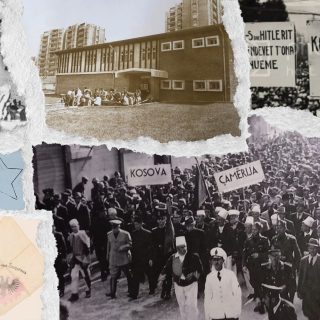

This has been manifested starting from the most visible ones: memorials, statues, and squares named after the most prominent heroes, which as if at once, covered all the cities, villages, and national roads of Kosovo. The whole of Kosovo was not only KLA, but also full of heroes and liberators. Everywhere, figures of men cast in bronze, which, in addition to showing a country emerging from a brutal and cruel war, also tell of new stories of memorialization and commemoration. Beyond their symbolism and historical meanings, these monuments serve to extend a certain political power.

But what are the theoretical-philosophical bases of the politics of memorialization and commemoration? Their foundation is the interpretations of time, or to put it in political terms, the interpretations of history: to whom does it belong, who owns the narratives, who owns the right to narrate the narratives, who determines the epistemological norm of the difference between truth and untruth, and what is considered true in the first place.

To put it in Michel Foucault’s language, every era is ruled by a “regime of truth,” which defines its truths and untruths, the stories that can be told and the stories that cannot be told, the stories that must be proclaimed and remembered and those that must be silenced or forgotten. Everything is delineated through wars of narratives and discourses. Whoever owns the narratives, owns the truth.

The politics of memorialization and commemoration always revolve around recognition and forgetting, collective and public recognition, and oblivion that covers everything else. Covering interacts with uncovering, not only as a process through which the necessary binary separation is created for an official policy of recognition, as a counterbalance, but also as a process of active forgetting.

The politics of forgetting are an ongoing investment of the politics of recognition and commemoration to maintain their own status as the only truth. Who and in what way gets recognition and is commemorated is a political relation. Official recognition and commemoration presuppose the existence of a single and immutable truth where the lines between the antagonizing forces are clearly drawn, where the separation between the aggressor and the victim is marked by an unbridgeable chasm, that the aggressor has always been the aggressor and the victim only a victim because there is a right side of history and a wrong side of it.

But not because everyone has committed crimes to the same level, and thus no one is exactly a victim and no one exactly an aggressor; not because the “autochthons” (or the “natives” in the Western discourse) are a bloody cabaret of prehistoric dances and intoxication – an auto-erotic self-exoticism. But because sustaining such a simplified discourse enables the continuity of the rule of a broad political, social and economic structure with vital and existential interests for maintaining power and permanent reproduction of itself. Because the enemy is no longer just the external enemy, the permanent biological threat.

This power and its instruments are now oriented towards the consolidation and upholding of domestic power against the inferior elements of the race, those who may not have fought in the war, those who are said to have sabotaged the liberation efforts, those who died ingloriously, weak men, women and minorities of every kind, “pacifists,” “citizens,” those who surrendered, spies and collaborators. After all, it does not matter whether you have done something, it is enough to be on the wrong side of history.

The Politics of Heroics

The power of the dominant narrative is such that it makes everything revolve around it and submit to its hierarchy of the heroic. All that is not subject to this power is excluded; everything that does not fulfil and reinforce the heroic ideal is silenced, all others must conform to the form of the supreme narrative.

It took Kosovo fifteen years to recognize the existence of victims of sexual violence during the war, more precisely to recognize the existence of women survivors of sexual violence, who constitute the largest number of abused persons, because for male survivors they were not ready even after such a long time.

The law that recognized the status of survivors and guaranteed them a pension as recognition for their suffering, first encountered resistance in the Assembly of Kosovo, from men and women MPs. The introduction of this category in the law on the status and rights of martyrs, invalids, veterans, members of the KLA, civilian victims of the war and their families, was as if it debased the image of the hero, as if it tainted the ideal of freedom, as if it made the war less heroic, more human, earthlier. Against such a quasi-religious conception, this constituted a sacrilege.

When their recognition finally came, it was accepted only on the condition that it yielded to the idea of the heroic, because only thus was the narrative of the ideal of freedom preserved unblemished and intact, but, in fact, this was how the power structure organized around it was upheld. They were clothed in the traditionalist, patriarchal categories of “our mothers and sisters,” symbols of the sanctity and purity of the nation, who must be protected and accepted because the nation is the big family of all of us.

As for “other” women, those of mixed race, Roma women, Serbian women, and those who find themselves on the wrong side of history, sexual violence against them was implicitly acceptable. They are what Judith Butler has called bodies that matter less: women’s bodies, foreign bodies, “deviant” bodies, LGBTQI+, non-white, and immigrant bodies, in short, all bodies that do not fit the image of the strong, heroic, and heterosexual body. The normalizing power of discourse is such that it constructs or tends toward ideal bodies to the exclusion of shameful bodies.

Even the form of the campaign to raise awareness on this category, to recognize and encourage them to apply for survivor status, has imitated the form of the dominant narrative, presenting them through the figure of the subject of heroine, as strong and courageous women. This does not negate the great work that is done with survivors by organizations that provide them with legal, medical, and psychological assistance. However, in the epistemological aspect, it imitates the hierarchical form of heroic and sacrificial power, with the triumphant subject at the centre of history.

Women have been excluded from such a heroic national narrative, and the recognitions that are achieved are difficult and well-deserved. Women are usually relegated to the roles of mothers, housewives who take care of husbands and children, who cook and tend to wounded soldiers, and serve as maids and couriers, roles that are not at all glorious and heroic to be sung. Even their role in the peaceful civil resistance during the nineties has never been recognized, a clear manifestation of the politics of forgetting.

Hierarchical differentiation also operates within the dominant narrative of the heroic, categorizing and ordering through a discriminating principle that remembers depending on political utility, belonging to a political group, or through family members who may hold positions of power and exert influence so that their family members are recognized and remembered by naming streets and schools after them. The unknown soldier does not have a grave!

Such a homogenising and hierarchical power renders knowing war impossible, it precludes recognition of pain, because it structures through a single knower, that marks and permeates everything only with the sign of the heroic, as the common metaphysical denominator.

Even Adem Jashari himself and his struggle remain unknown because the prevailing official discourse does not allow his recognition. His figure, work, and military resistance are remembered and commemorated. Still, from the beginning, almost before he fell, the whole thing was wrapped in the discourse of myths and legends, with an almost religious language. As such, after the war, he becomes politically usable and useful as the central figure of the heroic narrative. As dead, he serves the living, serves their power and its upholding. They need him only as dead, hence the slogan “He is alive”!

Due to his extreme instrumentalization and the lack of proper historical distance, knowing him and his military engagement remains impossible for now. His figure continues to be politically charged. From Kosovo to Albania, it continues to be used as a cannonball against political opponents, against Yugoslavs, Titists, and Yugo-nostalgics, against those who did not fight, against those who rejected the war, by those who find themselves on the right side of history against those who find themselves on the wrong side of it.

The rupture of the narrative and its pluralisation

Every collective human memorialization and commemoration results from power relations, reflecting the dominant narrative, which seeks to solidify itself and dominate among other narratives. A consequence of this is the marginalization of other stories, other forms of human suffering and experience, and the suppression of stories that oppose the dominant one. The recognition of other forms of narration requires the rupture of the main narrative, and this rupture must be radical because for the creation of new spaces of human narratives it is not possible to preserve the old hierarchical form that subordinates everything to the heroic subject. It is not a question of undoing those stories, because that would make no sense at all, but of reinterpreting and even rediscovering these stories and retelling them in new forms. This requires a reconceptualization of time and the ways we understand history.

Walter Benjamin outlines two radically different approaches to conception of time, or history. The first has to do with time as something past and closed once and for all, a static time stretched endlessly into the past as a continuous legitimation of the present. The past is the legitimating function of the present, it is subject to a linear progression of time, in which every present disappears forever into an irreversible past. This being so, the only orientation remains towards the present and the future. This political conception of time ensures its freezing because in this way the relations of forces are frozen, which are actually dominant and hierarchical power relations. Benjamin called this conception of the past as static and frozen the historicist approach.

The second conception concerns the past not as something dead, but as dynamic, as a field from which the present is reanimated, brought back to life by a living past, necessary for political action in the present. Truly the past holds many things irretrievably lost. Still, it also offers us the infinite remains of those things, objects, places, and ideals of the past through which the present opens up and orients itself toward unknown futures.

This opens up time for recognizing the stories of others, for recognizing their pains that have left their marks; it is a way of being present and in community with others. Discourse and unknown narratives are opened up by opening the thinking on history beyond the subject, unsung stories are unconcealed, and the monopoly on histories that define us in a certain time and space is broken.

This article has been produced as part of a cooperation between Sbunker and forumZFD Kosovo.