Besmire Kluna

It was September 1989 when the Gallery of the Academy of Sciences and Arts in Belgrade would make room for 1,247 Kosovo artifacts for a temporary exhibition. The contingent that included 571 ethnological exhibits and 676 archeological exhibits turned out to be the most long-term exhibition because they have not been returned to their country of origin even after three decades.

According to the data of the Protocol Book of the National Museum of Kosovo, signed by the then officials of the Ministry of Culture of Serbia, in 1989, it was decided that exhibits would go for a several months’ exhibition in Belgrade and then they would be returned to Kosovo as a permanent exhibition.

The shipment included fragments of artifacts, exhibits, archaeological rarities and a numismatic collection.

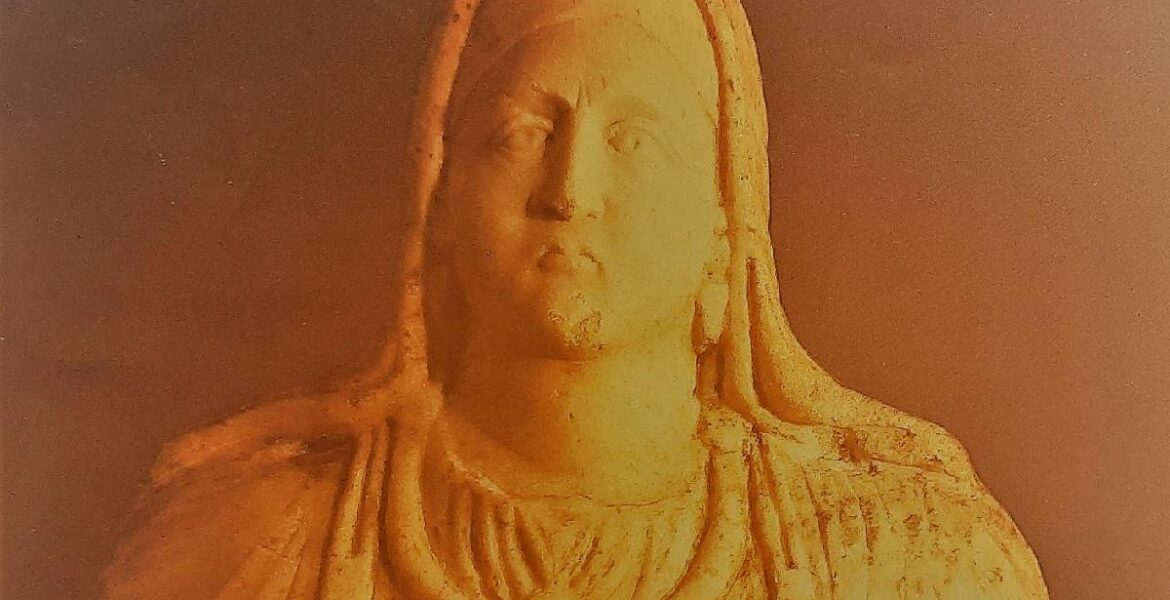

In 2002, the Goddess on the Throne, a terracotta of the archeological period of the 4th century (Late Neolithic), became the only exhibit that was returned to Kosovo after the war, at the time when the country was under the administration of the United Nations Mission (UNMIK).

Eternal silence

“There are 571 ethnological exhibits in Belgrade and 676 archeological exhibits belonging to the Iron Age, Dardanian, Roman and early medieval periods,” said Driton Avdiu, acting director of the National Museum of Kosovo.

Artifacts that define a country’s national identity, in many cases of uncertainty or conflict, can be removed from their countries of origin. But, according to museum officials in Kosovo, the non-return of exhibits from Serbia shows that the intention to remove them proved to be unkind.

The request for their return has been constantly repeated, but Avdiu demands that the return of artifacts should in no way be part of the ongoing negotiations in the Kosovo – Serbia dialogue in Brussels.

“The 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Assets should be used in countries where there have been armed conflicts, then the 1978 UNESCO Convention on the Return of Cultural Property to Countries of its Origin or in Case of Illicit Appropriation.” he says.

Kemajl Luci was one of the archaeologists that was working at that time and he says that there are documents showing that the entire material had been taken for a temporary exhibit. “Materials that are in Belgrade have been sent legally. But this issue has been politicized,” he says.

More than three decades since they had been taken from Kosovo, the artifacts continue to wait to be exhibited to the public again.

“The collections of artifacts and exhibits that are being held hostage are located in the basements of the National Museum Belgrade, locked in crates, in the dark, and forgotten,” says the archaeologist Milot Berisha.

The exhibits are only a part of damage to Kosovo’s cultural heritage done before and during the war. The massive destruction of cultural heritage during the 1998-99 war was carried out far away from the frontlines during an ethnic cleansing campaign and, together with those in Bosnia and Croatia, they constitute the largest destruction of cultural heritage in Europe since the Second World War.

Enver Rexha, director of the Kosovo Archaeological Institute, says that sanction methods should be found against Serbia to force it to return this cultural property.

“Serbia has violated international codes of Universal Cultural Heritage and the international community should force it to return the ownership of Kosovo’s material culture,” says Rexha.

Nora Weller, the director of Cambridge Academy of Global Affairs and a legal expert on the protection of cultural heritage, describes the taking of artifacts from the National Museum of Kosovo as “an additional act of further violation of national identity”.

“The removal aimed to eradicate signs of ethnic Albanian identity in the territory of Kosovo,” says Weller.

“Keeping the artifacts is just a further expansion of crimes that the state of Serbia claims to hide,” she added.

Archaeological research and studies in Kosovo have been conducted separately along ethnic lines for more than three decades.

“Among ethnological exhibits borrowed from the Museum of Kosovo, there are also exhibits of Kosovo Serb community,” says the historian Arianit Buqinca.

The leaders of the Museum of Kosovo addressed a letter, again this year, to the National Museum Belgrade, the Ethnographic Museum and the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, requesting the return of exhibits that belong to Kosovo, but this request continues to be ignored.

According to the Comprehensive Proposal for the Kosovo Status Settlement, known as the Ahtisaari Plan, Annex V Article 6, the return of archaeological and ethnological exhibits should have taken place within 120 days from the date of entry into force of this Settlement, but Serbia had not accepted this proposal and the return of the exhibits was never realized.

Valon Xhabali from the Organization “Ec ma ndryshe” [Walking differently], says that Serbia, as a member of UNESCO, is not entitled to keep artifacts that belong to another state. “Membership also means the commitment to observe organization’s conventions on cultural heritage,” he said.

According to the media official, Zana Fetiu, the Ministry of Culture of Kosovo has repeatedly requested the return of this collection that has been taken earlier. But Serbian authorities have not responded to any request so far.

“We have demanded responsibility from museums, and political responsibility from the Belgrade government, to fulfill an international obligation. We will not stop until the entire respective collection is brought back”, says Fetiu.

This article is a product of online training Dealing with the Past (DWP) / Conflict Sensitive Journalism, implemented by forumZFD-Program in Kosovo. The views expressed in this article are the responsibility of the author and they do not reflect the views of forumZFD.