They did not touch the frame, nor break the glass. They only took his picture. Even the poster of his face, set opposite the picture, was not touched. The frame is still in its place, and so is the glass, untouched. It is as if the picture disappeared into thin air. For how long has it been gone? How could we have missed it? I mean, it is not that it was hanging in the most visible place. The hallways of the cinema are long and narrow, painted in a light blue colour. Old posters from the past hang on these walls. Posters of motion pictures from another era. An era that is remembered with glory by some, and pain by others.

When you see these narrow hallways for as long as I have, you come to realise that they are there only to bring you to the main hall, the large one, where the films are screened. That was the only purpose these hallways served. Somehow, they were not designed to exhibit posters. They were not designed to have people sit there and have a chat about films. It seems like people would only pass through them to come into the big hall, immerse themselves into a different world – one of drama and action – and then go back to their everyday lives. The world within the cinema was their access to new ideas, beliefs, and concepts, also curated in a propagandistic manner to suite a particular political convictions system.

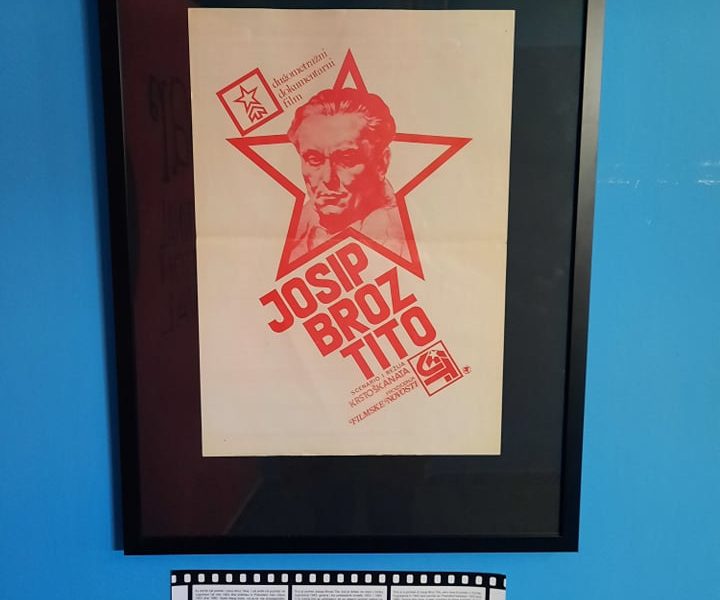

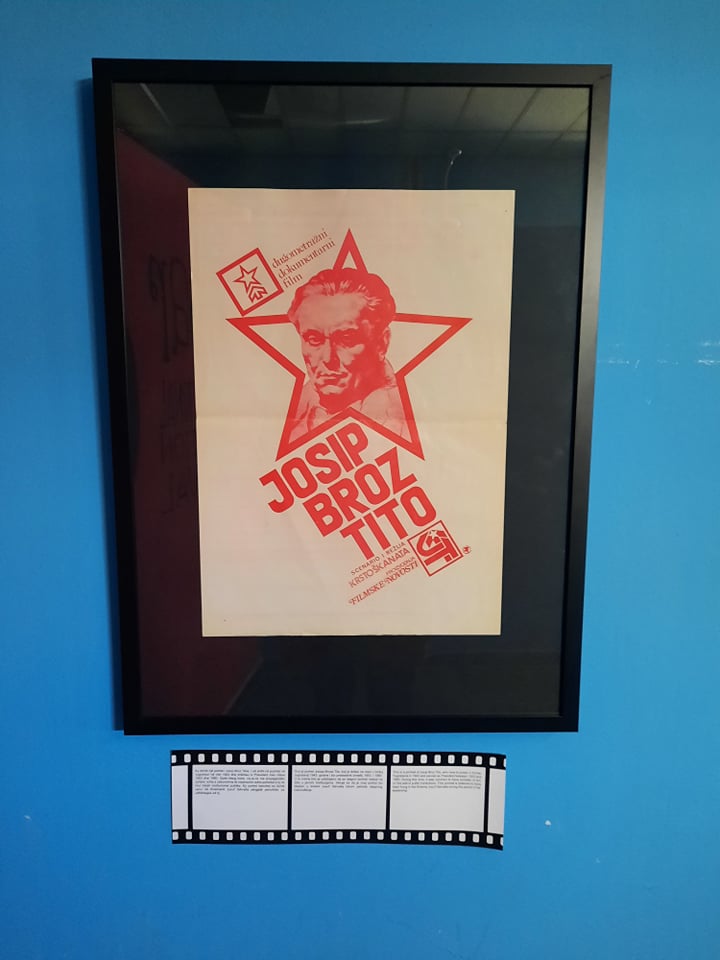

I have heard stories that the most action would happen before even getting to these hallways. People would gather in front of a small window trying to get their tickets to this other world. Everyone had their own technique on how to get a ticket. It is not that there were not enough tickets to buy. It is just that they wanted to get to that other world as soon as possible. So, people did not care about forming a line, they only cared about finding a way to get the ticket as fast as they could. Some with a more entrepreneurial spirit would form alliances with the workers selling the tickets, they would get a batch and then resell them at a higher price – they were called Tapkarosh. What a funny name! Some with smaller bodies would jump over people, and some with bigger bodies would use their huge hands to pass along the sides of people and somehow get their money in through the small window. Some had even found alternative ways of getting inside without paying at all. And once they got into those long narrow hallways, they would make their way towards the main hall and watch some of the films, the posters of which are still hanging in the same hallways. They would come to watch documentaries like “Josip Broz Tito” by Krsto Škanata, whose poster is hanging today in front of the missing picture of our protagonist – Tito.

When we first came to the cinema, we found his picture hidden amongst film reels in the projection room. After the war in Kosovo the staff of the Cinema had decided to remove it, from its place of glory. They, too, blamed Tito for what had happened.

Josip Broz Tito was known for his love of film. Together with his wife, Jovanka, he would watch a film every night. He was also involved in their production; he realised the importance that film had in shaping up culture. From stories I have heard, I think that people in Peja realised that the partisan films were eulogies towards those who had won the war, however, I think they preferred American Westerns and Bollywood films, as those are the ones that get usually mentioned. On the other hand, Tito loved American westerns.

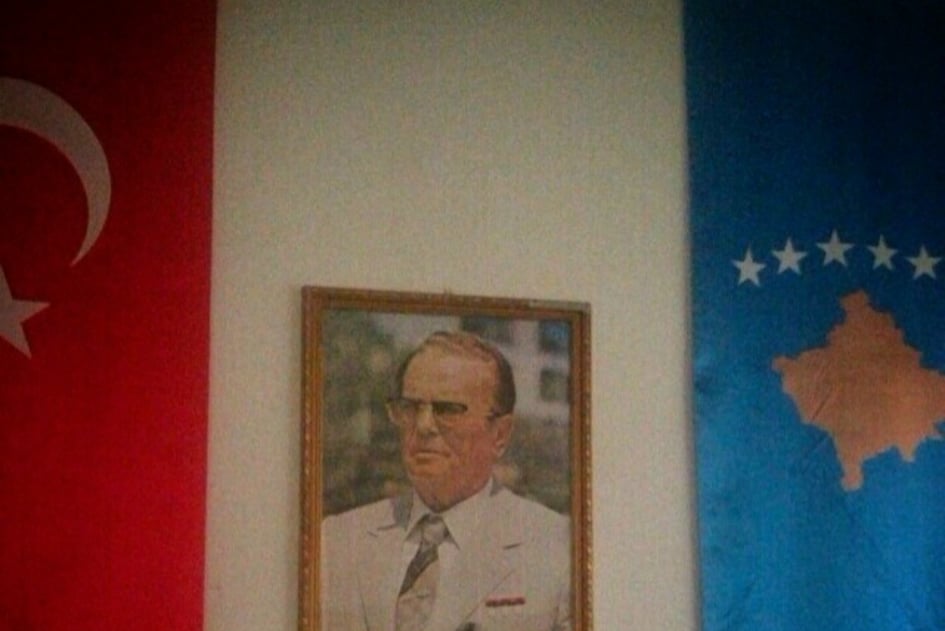

For most of us, the younger ones, who have never lived in that era, seeing his image was quite astonishing. I remember having mixed feelings. It felt rebellious to have his picture because of the current ones in power, but also having experienced the pain that Yugoslavia had caused to people in my community and family it felt wrong. Through the past 5 years that we have been here it has been sitting in different places. Across the toilet, at the main office, at the warehouse. Once it was even hanging in between a Turkish flag and a Kosovo flag, at the back of the building. The irony of it. Recently, one of the curators decided to place it amongst the other posters of the cinema. It somehow felt like it belonged there. This cinema was built during that time. It was built by the workers’ union. It was even called the Workers’ Cinema – Kino Rad. No bourgeoisie in this cinema. No fancy couches or chairs. Built under Socialist Yugoslavia. Alongside its development. Was it perhaps one of its previous workers who felt nostalgic of the glory of that time? Or maybe it was one of the current workers who was charmed by his stance and demeanour?

We first must establish the ‘why’? What was the motive for taking his picture? Was it someone who saw glory in that era, or someone in pain? Is it hanging on someone’s wall, or has it already been burned? In our city, Peja, you have both.

Like the rings of the trunk of a tree represent its age, our cinema and the films screened there somehow represent the history of this city from the 50s and onwards. After World War II the film industry in Yugoslavia was planned as a state-controlled activity driven by socialist political, educational, and cultural motives. Mainly influenced by the Soviet film industry. Starting from the mid-50s this approach changed, and more commercial films were being screened. Films coming all the way from the US, mainly American Westerns, Bollywood films, and what not. A decentralised industry organised through socially owned enterprises which were operating locally came because of crises of Soviet – Yugoslav relationships in the late 40s. This allowed for a more liberal approach in film production and distribution. Which also meant people’s relations towards the cinema were changing with the changes within these structures.

So, we have those who remember that time in its glory and Tito as the personification of that time. Marshall Tito, he made it possible for people to go and travel the world. With 10% of their salaries, they would pay for utilities, with 50% they could spend their summer in Spain. People had everything, and everything they had was better than before or after. They did not have corrupt politicians, nor super rich people, somehow everyone was equal. Or so they thought. Because there are also those who lost their loved ones to a political ideology, who were unable to read in their mother language or study in their primary language for that matter. They did not make a good living, nor were they travellingto Spain. They also have the resentment of the time that came post Tito, they somehow blame him for that too. He spoke the same language as the ones who started the war. So, who is it? Who took the picture?

The second question I have is: how? How did they take it? Was it during the last event we had, when there were hundreds of people commemorating the time of the mass student protest that was happening in the ‘80s, when the rights of the Albanians were being suppressed in Yugoslavia? After Tito’s death in May 1980, tensions amongst Albanians and Serbs within Kosovo intensified. In 1981, Albanian students started organising a protest demanding that Kosovo become a republic within Yugoslavia, and not a province within Serbia, which it had become with the adoption of Yugoslav Constitution in 1974. The protests intensified into widespread violent riots involving over 20,000 people. The picture of Tito was already being disintegrated.

It is hard to say that it was them who took it though. They came in, walked quickly through those narrow and long hallways, and got out. They did not stay for long; they were simply focused on what was going to happen in the main hall. To commemorate their past civic engagement. Also, his picture was at the end of the hallway, opposite the toilets. You really must know how to get there to see it. And the frame is intact. At least, that is how it looks. So, it should have been someone who really took their time. Removed it slowly and kindly put back the frame.

All I know for sure for now is that the picture of Tito is missing. It feels like his picture has been missing for some time now. The blue wall is still here. And the frame is still here. It now shows the blue walls of that long, narrow hallway, of the only cinema in the city of Peja, in Kosovo.

The workers’ cinema, built by the workers and saved by its people.

*When the article was written the walls of the cinema were blue, in the meantime the staff had decided to paint them red. Not related to the article in any way.

Vullnet Sanaja is a cultural activist and co-founder of a number of organizations and initiatives, such as Anibar, Network of Cultural Organizations of Peja, Animation Academy in Peja and Prishtina, Peja Jazz, and Into the Park Festival. Mr. Sanaja has been working in several NGOs involved in civic engagement, environmental education, and sustainable development through arts, such as ERA, Forumi Kulturor, and CYCC. Since 2010, he is the Executive Director of Anibar, an organization based in Peja, Kosovo, which commits itself in breaking civic apathy through cultural activism. Anibar is also the organizer of the only animation film festival in the country, and manages the only movie theatre in Peja. The organisation delivers education programs in Prishtina and Peja.